Metro air getting dirtier, deadlier for commuters

Credit to Author: racosta| Date: Fri, 28 Jun 2019 21:14:00 +0000

(First of three parts)

Anyone who routinely weaves in and out of the perilous roads of Metro Manila knows that it requires a certain formula of luck, timing and agility to wisely navigate one of the world’s most densely populated areas.

For everyday commuters like former teacher Curt Marvin Cruz, it can be a matter of life and death.

Last year, the 24-year-old traveled daily from his home in Quezon City to his workplace, a public school in Santa Rosa, Laguna province. His day began as early as 5:30 a.m. with him riding a variety of public transportation—jeepneys, buses, tricycles—to get from one point to the next. On a good day, when the formula worked, his minimum travel time was five hours.

But the long road trips soon took their toll. “I noticed a change in my asthma attacks: They became more frequent and took longer,” he said. “There were days when I needed to bring my nebulizer to school.”

A major culprit, he said, was his daily exposure to the dust and soot blanketing Metro Manila. With millions of gas-guzzling and smoke-emitting cars plying the choked roads, its air was also slowly suffocating its residents.

And daily commuters like Cruz, who are exposed outdoors for longer periods of time, bear the heaviest burden of breathing deadly air.

120K deaths in PH yearly

Worldwide, ambient or outdoor air pollution is considered a major killer, causing the deaths of some 4.2 million people in 2016 alone, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Including household air pollution, WHO estimates that 9 of 10 people breathe air containing high levels of pollutants, with 90 percent of related deaths happening in low- and middle-income countries in Asia and Africa.

The Philippines is among them. As many as 120,000 Filipinos die yearly due to air pollution from cars and fossil fuel burning, WHO reports. Related illnesses include lung problems, cardiac arrest and even cancer. With 45.3 deaths per 100,000 people, the Philippines has the third highest mortality rate in Asia due to air pollution, after China and Mongolia.

Government data indicate that mobile sources are largely to blame for the poor air quality.

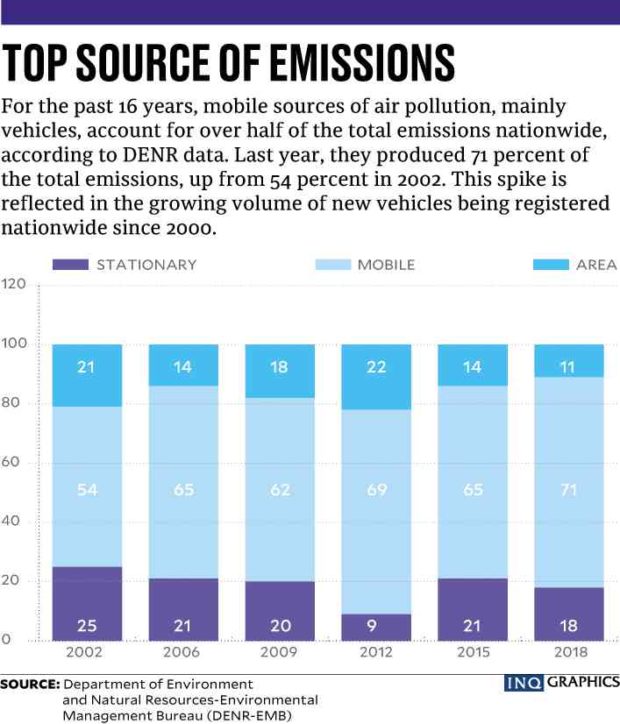

According to the National Emissions Inventory, compiled by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), emissions from transport sources accounted for over half the total emissions in the country from 2002 to 2018.

The danger has since increased: from 54 percent in 2002 to 71 percent, or nearly two-thirds of the total emissions, last year.

The two other sources of emissions—stationary sources such as industries, and area sources such as open burning—each only account for about a quarter or even less.

In the National Capital Region (NCR), deadly air from vehicles present an even more dismal picture. Latest data from the regional DENR show that vehicles are responsible for nearly 88 percent of pollutants in the metro in 2018.

These numbers align with the steady increase in registered vehicles in Metro Manila and elsewhere. Land Transportation Office records show 11.5 million registered cars nationwide last year, with 2.7 million in the metro. The number marks a whopping increase from the start of the millennium: only 3.7 million vehicles registered nationwide, including the 1.2 million in the NCR.

Most exposed

With cars clogging urban centers, polluted air also affects sectors that have little to do with the emissions around them.

“Those who cannot afford enough ventilation in their homes and those whose occupations force them to be exposed on the road are most vulnerable. Usually, these are the people at the lower levels of society,” said Dr. Mylene Cayetano, who leads the Environmental Pollution Studies Laboratory (EPSL) at the University of the Philippines’ Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology (UP IESM).

Recently, researchers led by scientist Dr. Emmanuel Baja of the National Institutes of Health in UP Manila assessed the condition of over 100 Metropolitan Manila Development Authority traffic enforcers deployed on Edsa. The enforcers’ exposure to black carbon and heavy metals from the emissions was found to have affected their lung functions and blood pressure.

A component of a mix of solid and liquid particles called particulate matter (PM), black carbon comes from gas and diesel engines and is the product of incomplete combustion.

The commuting public, particularly students and employees who daily brave rush-hour traffic, are also very much at risk to the adverse impacts of polluted air.

Being a commute expert, Cruz is no stranger to the dangers posed by the air he breathes. He has had a fair share of trips to emergency rooms due to extreme asthma attacks that required intravenous corticosteroids just to open his airway.

Cruz wears a face mask or uses a handkerchief to cover his nose and mouth when he travels. But these little defensive acts do not prevent him from smelling strong fumes from vehicles or inhaling possible airborne organisms in packed vehicles, he said.

Black soot

Studies have shown that the high volume of cars and heavy traffic in the metro contribute to higher levels of air pollutants, such as PM.

Two pollutants known as PM2.5 or PM10 measure 2.5 or 10 micrometers or less, respectively, finer than a single strand of hair. But from a car exhaust, they can come in such high concentrations that their aggregates are visible as black soot, said Dr. Gerry Bagtasa, head of the UP IESM’s Atmospheric Physics Laboratory.

A study by the EPSL in 2018 found that the highest PM concentrations were recorded during daily rush hours, particularly between 7 and 9 in the morning and between 8 and 9 in the evening, in roadside monitoring stations at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, Muñoz in Caloocan City, the Lung Center of the Philippines in Quezon City, and Ayala Avenue in Makati City.

The study also found that Thursdays and Fridays held the most pollutant concentrations within a week, declining into the weekend with fewer cars on the roads.

In terms of exposure, those positioned closest to smoke-belchers—for example, those waiting for or alighting from jeepneys or buses—would naturally be more exposed to the pollutants, Bagtasa said.

He cited a personal exposure experiment that he conducted in 2015 on Edsa, which showed certain areas of concern where soot had reached dangerous levels. On a weekday, these included Muñoz, Cubao, Shaw Underpass and Ayala Underpass. The volume of idling passenger buses and the limited space in the tunnels affected the soot measurements in these sites, he said.

Similar to the 2018 trend, these measurements would drop significantly on weekends.

“Let’s connect it: You have your rush hours, then your cars are in idle mode in traffic. At nighttime, the atmosphere contracts, so there is smaller space for the air to travel,” Cayetano said. “And then you have all these people exposed outside, the whole community.”

Experts agree that the rainy season presents a respite from pollution, with rains cleaning the air of its pollutants, almost like a blessing from the heavens.

“But storms don’t happen every day. Emissions do,” Cayetano said.

No public clamor

Emissions also imperil the environment.

Black carbon, for instance, is a short-lived climate pollutant. It stays in the atmosphere for a shorter period of time, but can potentially contribute to global warming by absorbing solar radiation energy and converting it to heat, according to the Climate and Clean Air Coalition.

Experts and advocates agree that there is a growing awareness of the impacts of polluted air, but there is still no public clamor for the government to ensure clean air for everyone.

“People usually … won’t complain on issues that they can tolerate. Commuters, pedestrians, drivers and bikers will just perhaps tolerate the pollution, but there are long-term impacts,” said Khevin Yu, climate and energy campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

Yu said the public silence may also be rooted in the lack of available transportation alternatives. As the public transport system, which is often blamed for pollution, takes a turn for the worse, more and more people are forced to buy their own cars, compounding the problem in the streets and in the air that we all breathe.

(To be continued)