The First Lesbian Porn and 10 Other Revealing Artifacts from Lesbian History

Credit to Author: Oriana Leckert| Date: Fri, 14 Jun 2019 20:26:30 +0000

In the early 1970s, thrumming with the excitement and possibilities of the gay liberation movement, a group of New York lesbians started to take stock of their community. They realized that, like any other marginalized group, if they wanted to preserve the specific struggles, triumphs, and contours of their movement, they needed to collect their own stories. “Our history was disappearing as rapidly as we were creating it,” says Deborah Edel, co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, in a video the organization made about its origins. “So a few of us said, Why don’t we just start our own collection? We’ll put together what we have and build from there.”

The Lesbian Herstory Archives opened in 1974, in the Upper West Side apartment that Edel shared with her then-partner and co-founder Joan Nestle. They started by filling a milk crate with some flyers, photographs, pamphlets, and ephemera. Once that was full, they parceled out space in the pantry. When that began to overflow, the collection took over the spare bedroom, then the living room, and as it crept through the rest of the apartment over the next decade, the collective, which was by then a half-dozen women, realized the archive needed a home of its own.

In 1990, after many months of fundraising, touring slideshow presentations, and rent parties, the group purchased a three-story building in Park Slope, Brooklyn. By 1993, they opened their doors to the public, inviting in anyone looking to learn about lesbianism. Today, 45 years after it began in a milk crate, the archive contains some 20,000 photographs, thousands of books, massive collections of newsletters, magazines, periodicals, flyers, diaries, correspondences, video and cassette tapes, theater scripts, posters, banners, matchbooks, buttons—and the list goes on.

As American pop culture has gradually become more inclusive, even people not terribly focused on queer stories likely know specific shards of LGBTQ history—the rise and fall of Harvey Milk, the heroes and victims of the HIV crisis, the erotic portraits of Robert Mapplethorpe. Very few of those tidbits, however, shed light on lesbian history. Today, ephemera like what’s housed at the LHA gives us a glimpse into the rich, surprising stories that have long been ignored. These objects reveal intimate details about the lesbians who left them behind and the fascinating lives that they led. Below, find a list of 11 of those moments and people worth remembering, illustrated through artifacts from the LHA.

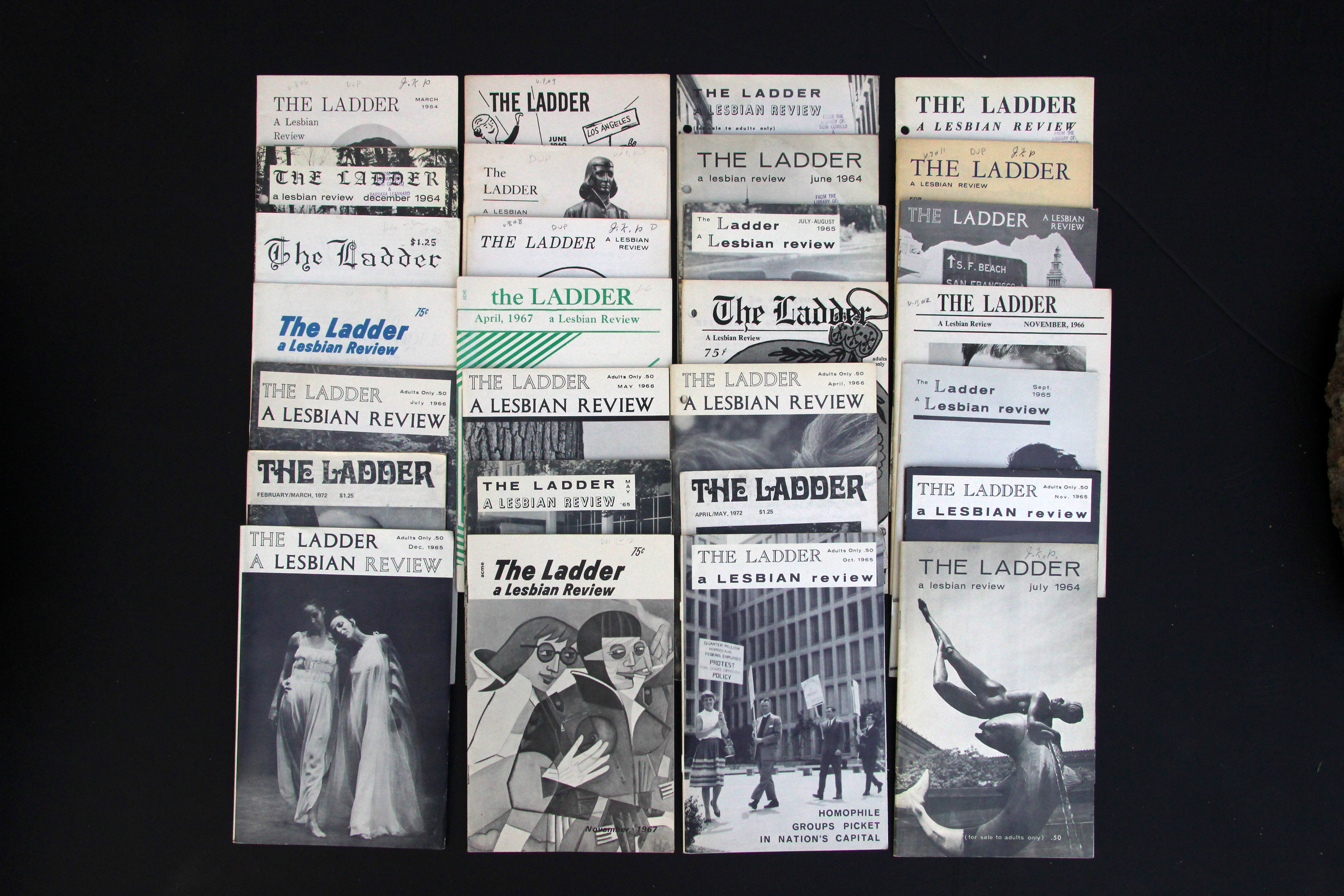

The first national lesbian magazine

The Daughters of Bilitis, the first national lesbian social and political organization in the U.S., was founded in San Francisco in 1955. The following year, the group began publishing The Ladder, the country’s first nationally distributed lesbian serial publication. The monthly magazine, which was always mailed in anonymous manila envelopes, contained news, editorials, poetry, short stories, letters, and a running bibliography of lesbian literature. When the Daughters of Bilitis disbanded in 1972, the group donated their entire lending library to the LHA.

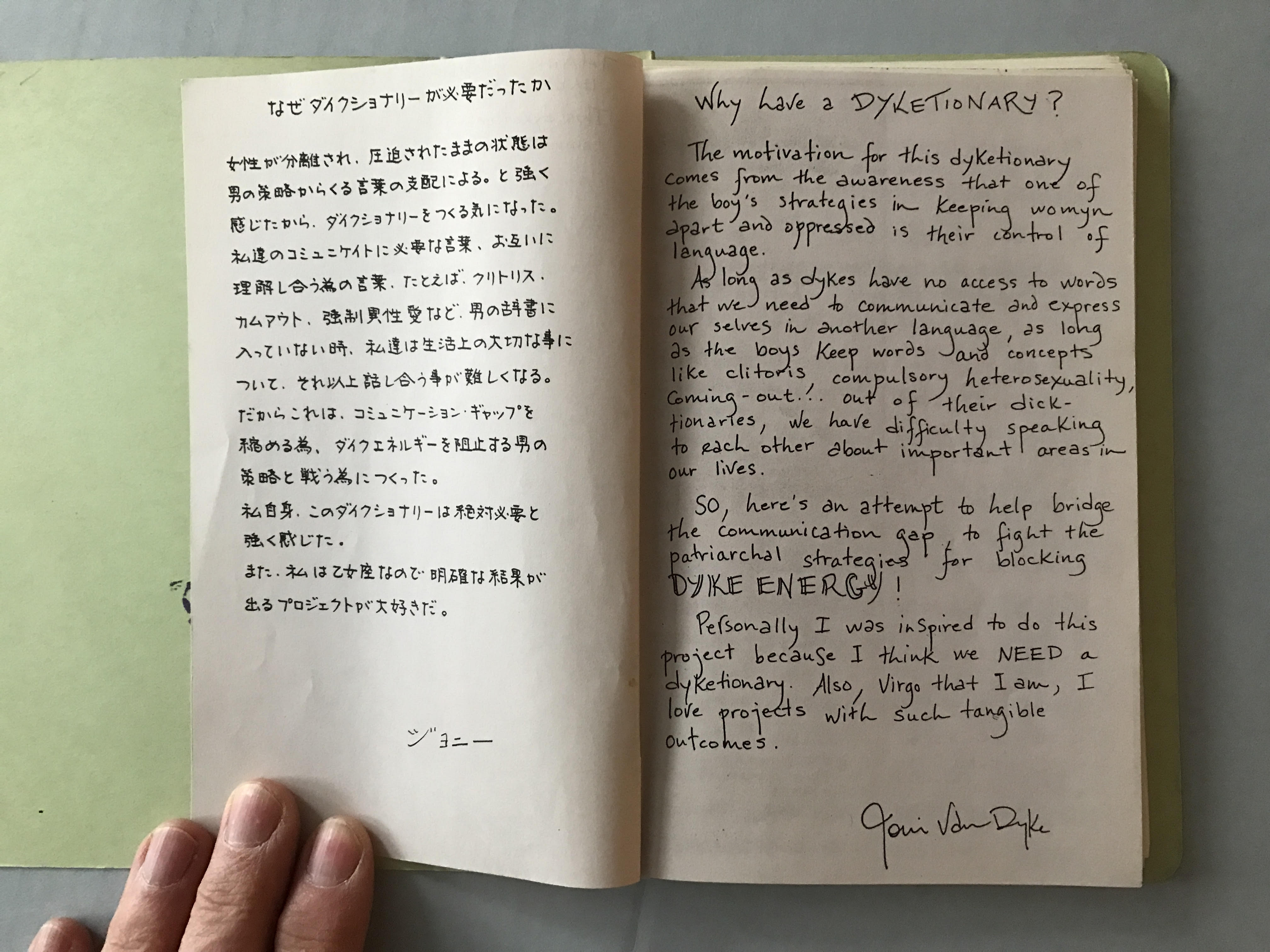

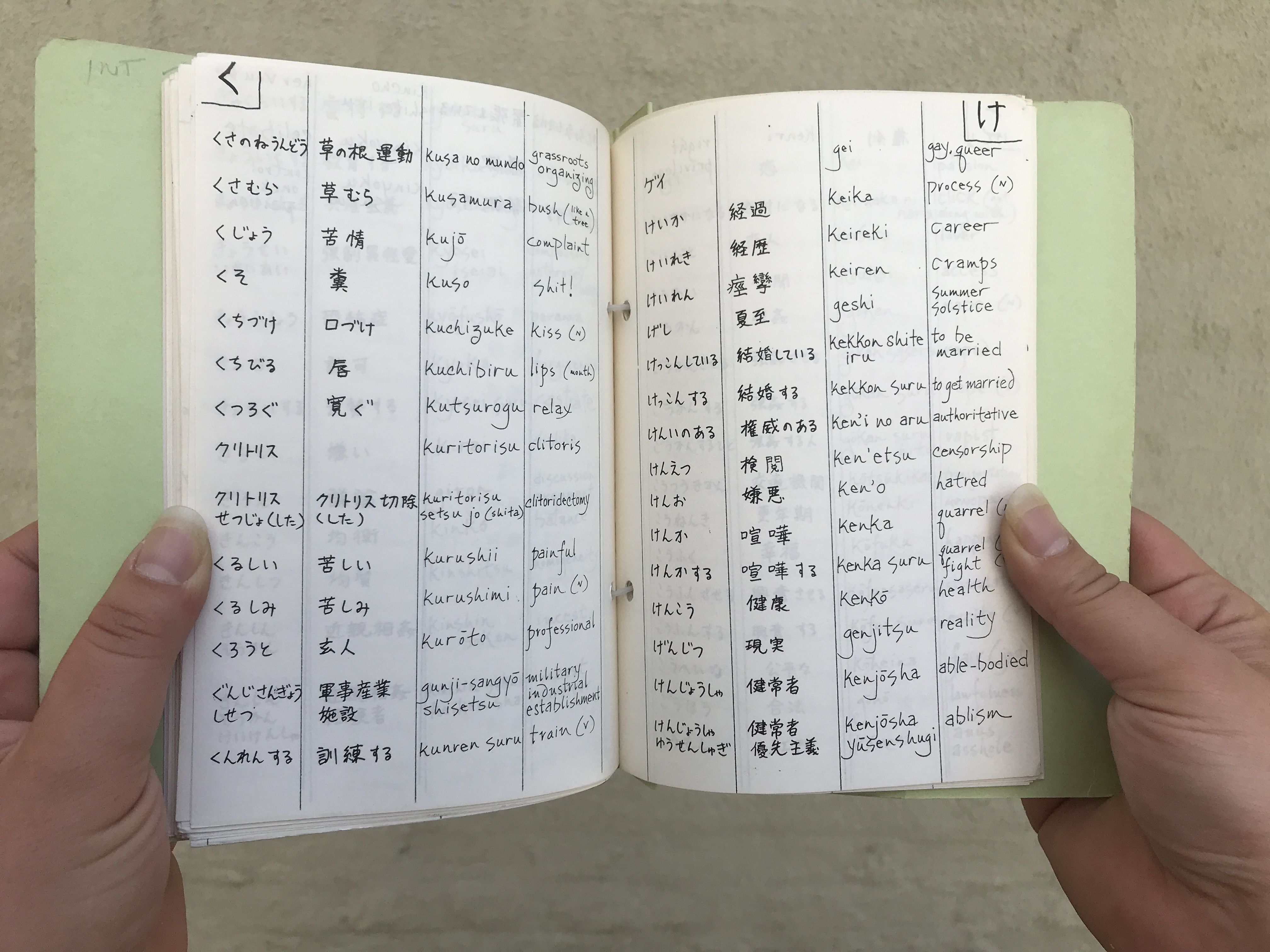

The Japanese Dyketionary

At the LHA, books are shelved alphabetically by first name, “as a gentle reminder of the fact that women lose their names very often,” explains Saskia Scheffer, who’s been volunteering as one of the archive’s 10 or so co-coordinators since 1989. So The Japanese Dyketionary can be found under “J,” for the (presumed) pen name Joni van Dyke. The beautiful, handwritten and hand-bound book contains hundreds of words and phrases, like “femme,” “bush,” “clitoris,” and “fag hag” in three languages: English, casual Japanese, and formal Japanese. There has long been a current of lesbian activism in modern Japan, which can be traced to 1975, when a dozen women became the first group to publicly identify as lesbians, publishing a single issue of a magazine called Subarashi Onna (Wonderful Women). In Tokyo in the 80s, a community of English-speaking lesbians began to form, and in 1985 they began holding in-person gatherings called uiikuendo (“weekends”) as part of the International Feminists of Japan conference. Uiikuendo was one venue where Dyketionary was circulated. As van Dyke explains on the title page, the book is “an attempt to help bridge the communication gap to fight the patriarchal strategies for blocking DYKE ENERGY!”

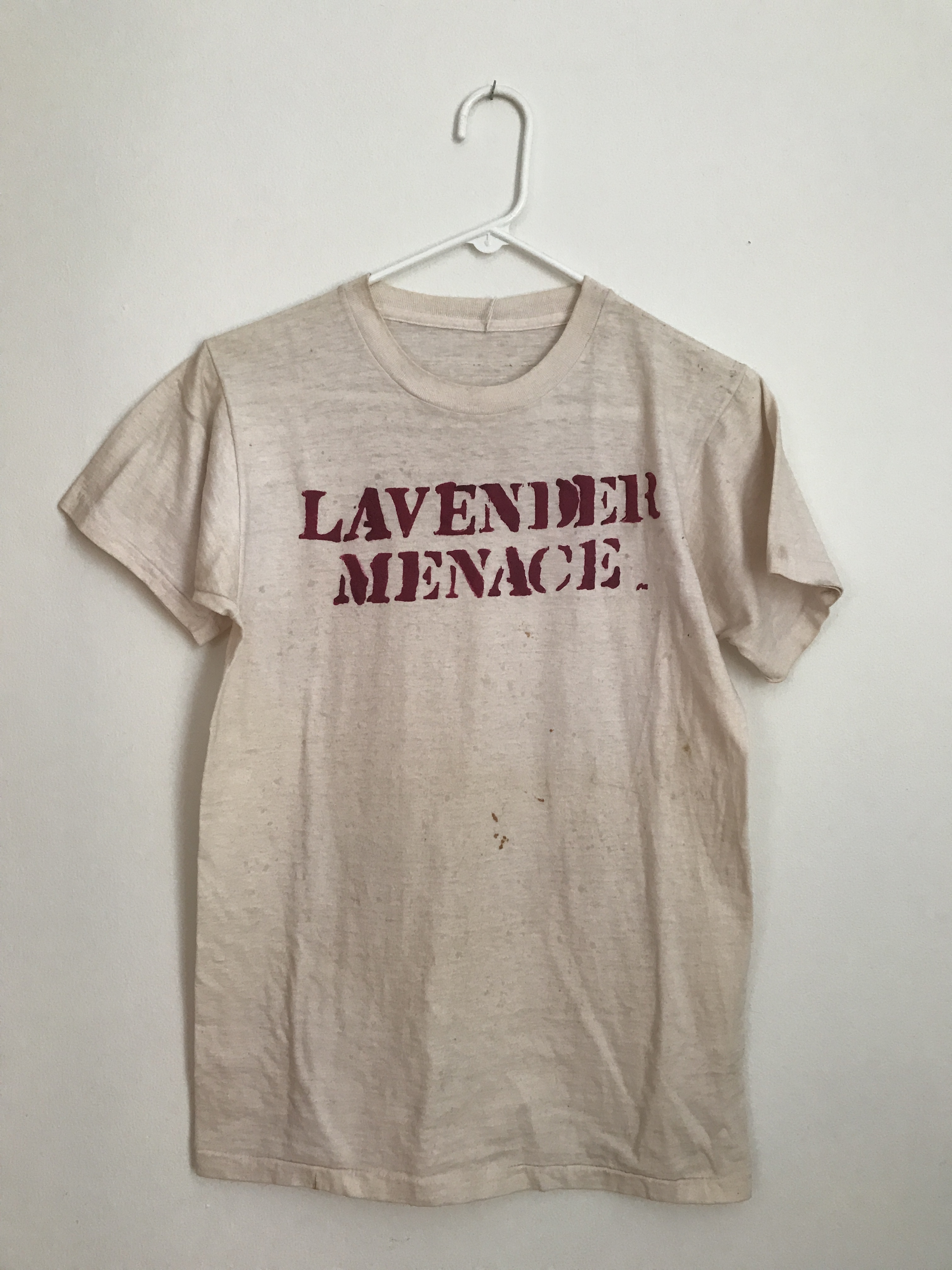

A shirt that reclaims an angry epithet

On May 1st, 1970, writer and activist Rita Mae Brown led a group of 40 women in a collective action at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City. Betty Friedan, a prominent second-wave feminist and founder of the National Organization of Women, had angered Brown (and many others) by referring to lesbians, whom she did not want as part of her movement, as a “lavender menace.” Brown and her cohort infiltrated the congress as Friedan was about to speak, cut the lights, and filled the aisles of the auditorium. When the lights came back on, all the women were wearing handmade T-shirts emblazoned with the phrase “Lavender Menace.” They began yelling demands for the feminist movement to embrace lesbians, and handing out copies of “Woman-Identified Woman,” a manifesto-like publication that the organizers of the action had co-written for the occasion and signed “Radicalesbians.” After the action, the organizers continued to use the new moniker. They would go on to serve as key figures in the lesbian feminist movement.

Pulp novels that circumvented the obscenity laws of the time

With titles like That Other Hunger, The Delicate Vice, The Evil Friendship, and The Odd Girls, lesbian pulp novels of the 50s and 60s were certainly not subtle in their prurience. Although mainstream publishers allowed the risqué novels to circulate, due to the strict obscenity laws of the time, the female characters had to be punished for their indiscretions and offenses against heteronormativity in order for the books to make it to print. To get past government censorship, any lesbian characters needed to give up her “wicked” ways by the end of the book and settle down with a man, or else lose her child, her job, or even her life. “You could be as lecherous and steamy as you wanted,” Scheffer says, “but you could not give them a happy ending.” Still, when these books were being produced, “they were among the only places where lesbians could read about themselves,” Scheffer adds. That’s why the archivists at LHA label them “survival literature.”

Photos of lesbian icon Mabel Hampton

Mabel Hampton is an icon of New York City’s lesbian history. She was a dancer and performer during the Harlem Renaissance, a gay-rights activist and philanthropist later in life, and an out lesbian through it all. Born in North Carolina in 1902, Hampton lived in New York City for all but her first few years of childhood. She spent much of her young adulthood as a dancer in Harlem’s artistic milieu as well as performing in Coney Island and throughout New York, proudly surrounding herself with many of the era’s most prominent queer Black women. Hampton met her lifelong partner, Lillian Foster, in 1932, and the couple lived in the Bronx together for more than 40 years, until Foster passed away in 1978. (Their apartment building is listed as an NYC LGBT Historic Site.) After that, Hampton went on to live with LHA co-founder Joan Nestle, in the apartment that originally housed the archives. Nestle created an extensive oral history of Hampton’s life through many interviews, and upon her death, Hampton donated all of her and Foster’s personal papers, memorabilia, letters, books, and ephemera to the archives.

The first women-run lesbian erotica magazine

As a reaction to what many felt was a deep strain of prudishness in the feminist movement at the time, On Our Backs was founded in 1984 as the first women-run, sex-positive, lesbian erotica magazine in the U.S. Throughout the 70s and 80s, there was a sharp divide between lesbians who downplayed talking about sex because they didn’t want it to define them in mainstream culture, and those who wanted sex to be celebrated and central to their identities. On Our Backs, which was published until 2006, was named in reaction to the long-running radical feminist (and often anti-porn) newspaper off our backs, which ran from 1970 to 2008. Over its 20+ years, On Our Backs published an array of groundbreaking and controversial erotic writing, often exploring social and political issues around lesbian sex and relationships, from writers like Dorothy Allison, Lucy Jane Bledsoe, Sarah Schulman, Thea Hillman, Jewelle Gomez, Patrick Califia, and Red Jordan Arobateau.

The first porn for women

Nan Kinney, one of the co-founders of On Our Backs, wanted lesbians to have more than just written erotica, so in 1985 she founded Fatale Media, the first company to make porn for women, which is still active today. Shadows, Fatale Media’s first release, promises “passion and spontaneity [that is] refreshingly genuine” from two women who are lovers both on-camera and off. A later Fatale film, Bathroom Sluts, was partially filmed at the LHA, “and in good lesbian fashion, the video ends with the participants proudly processing why they made it,” says Scheffer.

The only known recording of Paula Gunn Allen

Over her lifetime, award-winning Native American poet, literary critic, and scholar Paula Gunn Allen produced several books of poetry, scholarly works, and edited anthologies. Her groundbreaking 1986 book, The Sacred Hoop, posited that European scholarly and historical works had framed Native American society through a patriarchal lens, diminishing the important roles women took on in politics and culture. Her scholarly work was considered both controversial and influential, and her acclaimed books of poetry helped bring a Native American literary presence to the United States. She did not identify as a lesbian until later in life, after several marriages to men. A few years after her death in 2008, a researcher at the LHA discovered a cassette with a spoken-word poetry performance by Allen in 1980, which had taken place at the archive’s original Upper East Side location. It is the only known recording of Allen’s voice.

The moving diary of an ordinary lesbian from 1950’s Ohio

One of the principles of the LHA is that a person doesn’t have to be well-known to be remembered. “We don’t care whether you’re important or famous or even good or bad,” says Scheffer. “You can have your own special collection here.” One of the largest of those special collections is that of Marge McDonald, a lesbian who lived in a small Midwestern Ohio town in the 50s. She was a shy, self-described loner who lived most of her life extremely closeted. But she kept extensive, detailed diaries of her hopes and fears, her budding understanding of her own sexuality, and her inability to act on or discuss it with anyone in her closed-minded world. Among the 1,500 pages of diary entries from 1955 to 1957 is an account of her first visit to a lesbian bar—she’d concocted an elaborate fantasy for her friends, involving an imaginary boyfriend who wanted to see what it was like inside, “just for kicks”—and her first lesbian kiss, of which she wrote: “I could never describe my feelings so I won’t even try. It is sufficient to say that as long as I live, I shall never forget that moment—or the kiss.” When McDonald died, a lawyer called the LHA and said they had three days to pick up her entire personal archives; she had bequeathed everything to them in her will, effectively coming out to her family for the first time.

Memorabilia from Vietnam army medic Mary Minucci

Mary Minucci was an army medic and a noncommissioned officer in Vietnam. She was highly decorated, receiving a Vietnam Service Medal with six Campaign Stars, National Defense Service Medal (1 Oak Leaf Cluster), Bronze Star Medal, Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, and the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Palm. After her military service, she traveled to Papua, New Guinea, teaching native people to use Western medicine. She and her partner, who was also in the military, lived their lives deeply closeted. Minucci contracted three different kinds of cancer after her time in the service, and it was only after her death that her family gave permission for her to be named and recognized as a lesbian. It was an unlikely thing for Minucci’s story and her lesbianism to come out; given the extensive policing of sexuality for United States service-members throughout history, so few personal histories of queer people in the armed forces will ever be known.

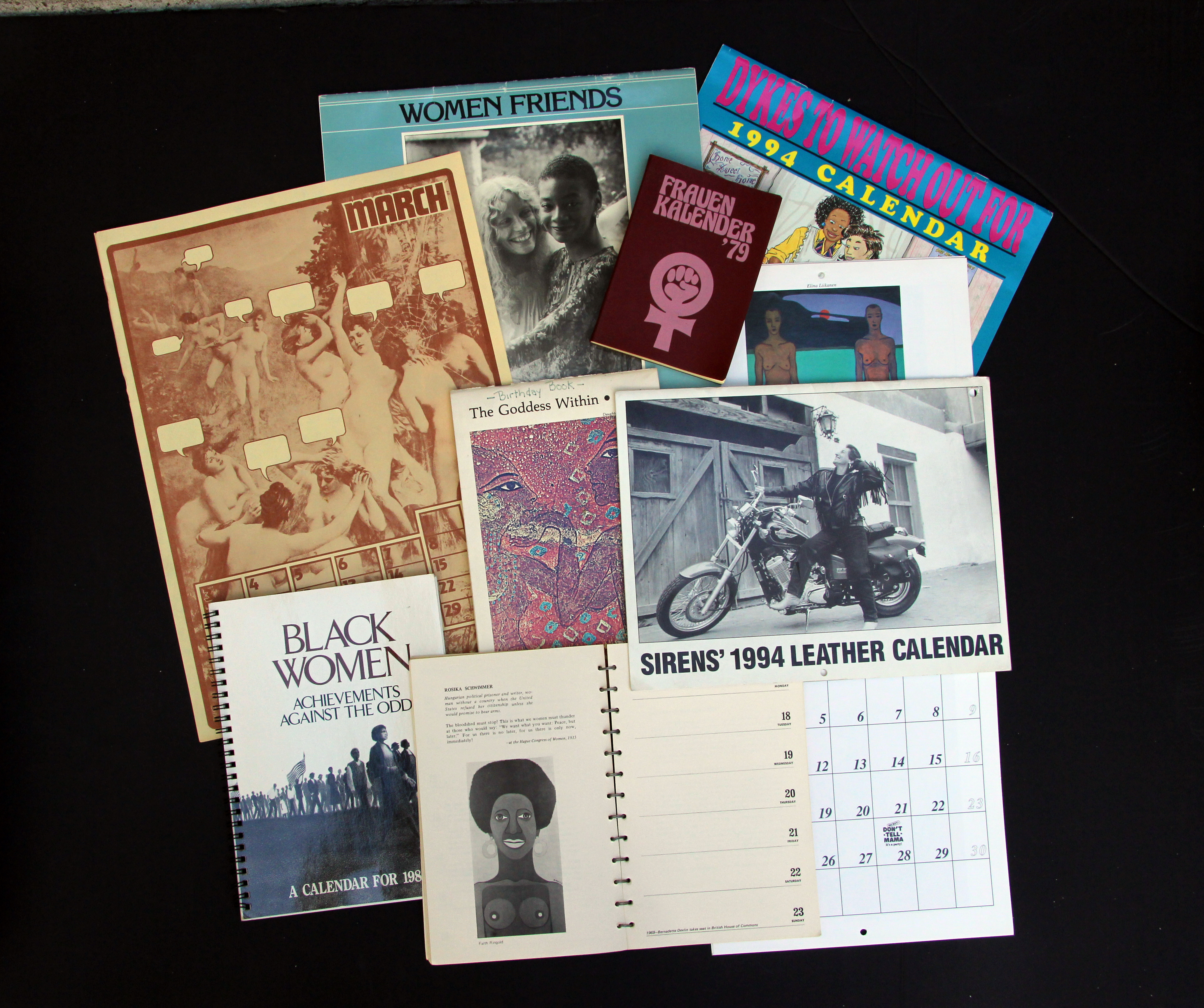

Calendars and daybooks that were used as subtle signals

Among the quieter, more personal items that tell queer stories are the handmade and small-batch paper goods that organized people’s lives. Before the digital age when lesbians could congregate in chat rooms and online forums, women often signaled their persuasion to one another with simple things like the calendars on their walls and the date books in their pockets. Some of these would later become mass-produced, like wall calendars featuring “Dykes to Watch Out For,” Alison Bechdel’s wildly popular long-running comic series, and “Sirens Leather Calendars,” made by the Sirens Women’s Motorcycle Club, the oldest and largest in NYC. Others were only produced in much smaller runs, and still others were handmade with care and distributed only to friends. In the 80s and 90s, these sorts of books were easy to produce cheaply and were widely used. Scheffer herself carried the small, red Vrouwen Kalender year after year; that particular date book was also available in English (“Woman’s Calendar”) and German (“Frauen Kalender”).

For more people, places, and moments from lesbian “herstory,” follow the LHA on Instagram .

This article originally appeared on VICE US.