An Oral History of ‘Transworld Skateboarding’ Magazine

Credit to Author: Hanson O’Haver| Date: Thu, 30 May 2019 19:29:10 +0000

In early March, subscribers to Transworld Skateboarding (TWS) got notice that the magazine was ending its print edition. In its place, they would receive issues of Men’s Journal for the remainder of their subscription period. The news was met with disappointment, if not total shock. The skateboard rumor mill had been whispering about the fate of Transworld magazine since early February, when the Enthusiast Network (TEN), which owned Transworld, was bought by American Media, Inc. (AMI), best known for publishing National Enquirer.

Many feared that the 36-year-old skateboard institution was dead, but while several employees were laid off, Transworld Skateboarding continues online. Still, the brand is far reduced from the thick magazine of its glory days, and has been for quite some time. Since the mid-90s, the skateboard magazine and its parent company, Transworld Media, have been bought, sold, and folded into other media entities in a confusing variety of ways. Through it all, TWS has held a special place in the hearts of skateboarders.

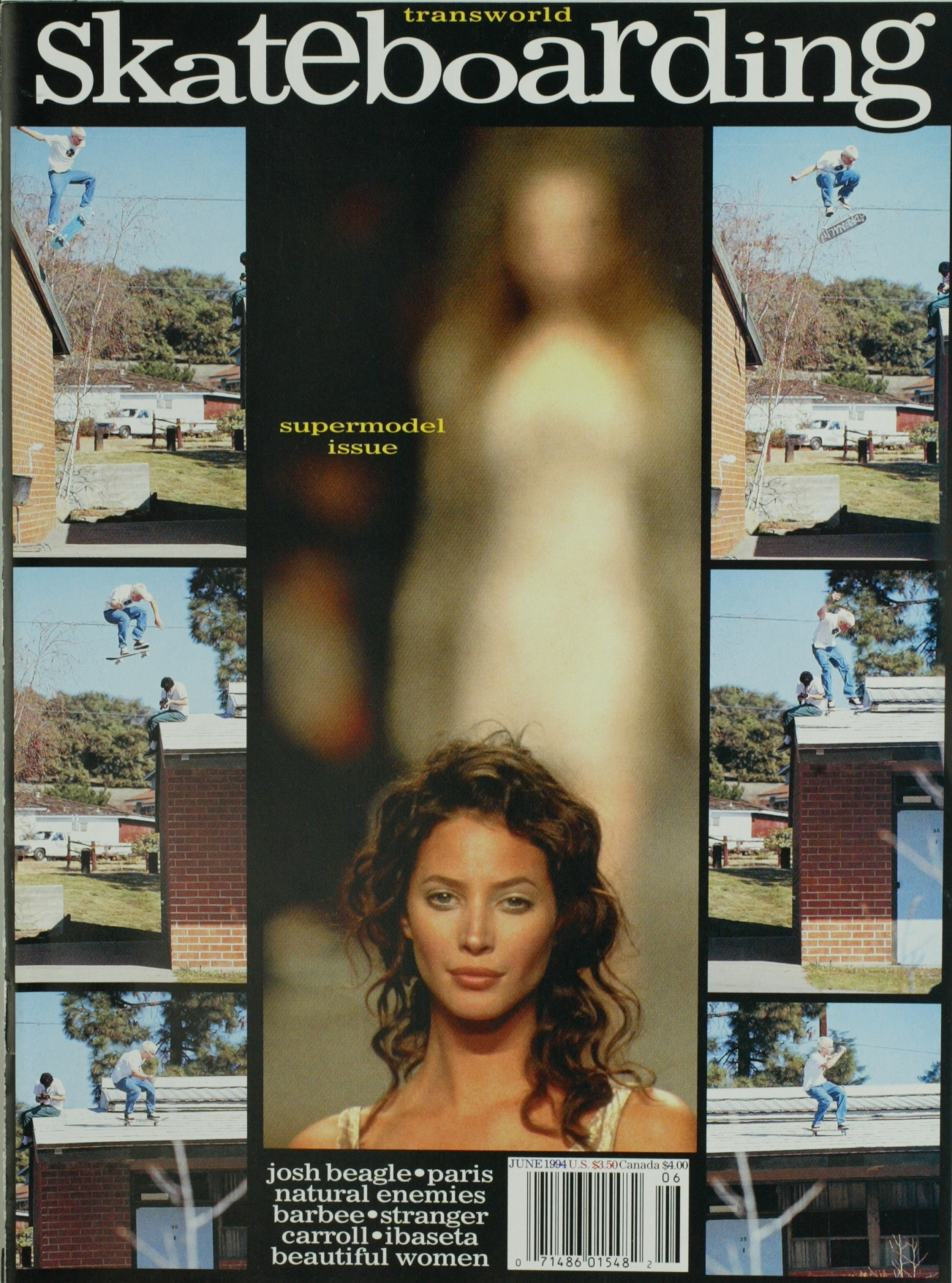

Thrasher, the only mainstream American skateboarding magazine still in print, has been called skateboarding’s Bible. If that’s the case, Transworld functioned as something of a cross between skateboarding’s TIME and its LIFE. With high-quality photos and parent-friendly articles, Transworld was the definitive publication of skateboarding’s boom years (think X Games, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, and puffy skate shoes). It had the biggest pros, the most ads, and the largest subscriber rolls.

In an effort to take stock of Transworld’s impact on skateboarding and the lives of the people who put it together, VICE asked some key figures from the magazine’s history about their time at the publication and their thoughts on its closing. In many ways, the conversation around Transworld’s decline parallels that surrounding other publications in the last decade: the rise of the internet, the recession, and magazines being treated as short-term commodities. What sets Transworld apart from other media entities, however, is that everyone VICE spoke to described their experiences with the magazine in overwhelmingly positive terms.

Larry Balma was an avid skateboarder and commercial fisherman in San Diego when he started Tracker Trucks in 1975. Previously skateboard trucks had mostly been modified versions of roller skate trucks. With their wider base, Tracker played a pivotal role in the transformation of skateboards from toys into, well, more capable toys. By the early 80s, Balma had seen skateboarding’s popularity spike and crash twice, once during the 60s “sidewalk surfing”–era, and again in the late 70s. When things began picking back up in the early 80s, Balma and Tracker employee Peggy Cozens came up with a strategy for keeping the industry healthy.

Larry Balma, founder, Tracker Trucks; co-founder, Transworld Skateboarding: In ’82 skateboarding started getting some momentum again, and the youngest kids were your body of buyers. When you turn 16 you get a car, you get a girlfriend, you might drift away. Say there’s a 13-year-old in Phoenix who wants a skateboard. He’s gotta get his parents to buy it, so they go to the local sporting goods shop. They really didn’t have many skateboards because it was so new and so off the wall—what they had was Thrasher, and Thrasher had the mail order companies in there. His dad takes the magazine and there’s guys throwing up and smoking weed and all the gnarly stuff, because Thrasher was a counterculture thing. It was great for everybody who was a little bit older, and it’d be fine for the younger kids, too, if their dad didn’t see it first. He’d look at it and say, “Johnny, let’s go over here and look at the soccer balls.”

Peggy Cozens, co-founder, Transworld Skateboarding: We weren’t satisfied with what was available in the media at the time, so we wanted to help grow the sport.

Garry Scott Davis (GSD) , pro skater, 1985–89; writer, editor, and art director, Transworld Skateboarding, 1983–93: In early 1983, I got a call from Larry asking if he could borrow an editorial out of my zine Skate Fate, to use in a new Tracker newsletter. I said yes, of course. A month or two later, the first issue of Transworld Skateboarding showed up in the mail. I was blown away.

Peggy Cozens: Basically, we called people and said we were going to do a newsletter—we didn’t tell them it was a magazine—and asked if they would send their ads to us. I can’t remember the number of pages—56 or something—but we got it printed and I called around to the distributors and asked them if they would please distribute these with their orders to the shops. We did that with the first three or four issues, all for free, and then sent out an invoice with a letter asking if they would pay either their advertising bill or their distribution bill, or both, and saying that we were going to start billing with the next issue. And people paid. They were on board once they saw what we were trying to do.

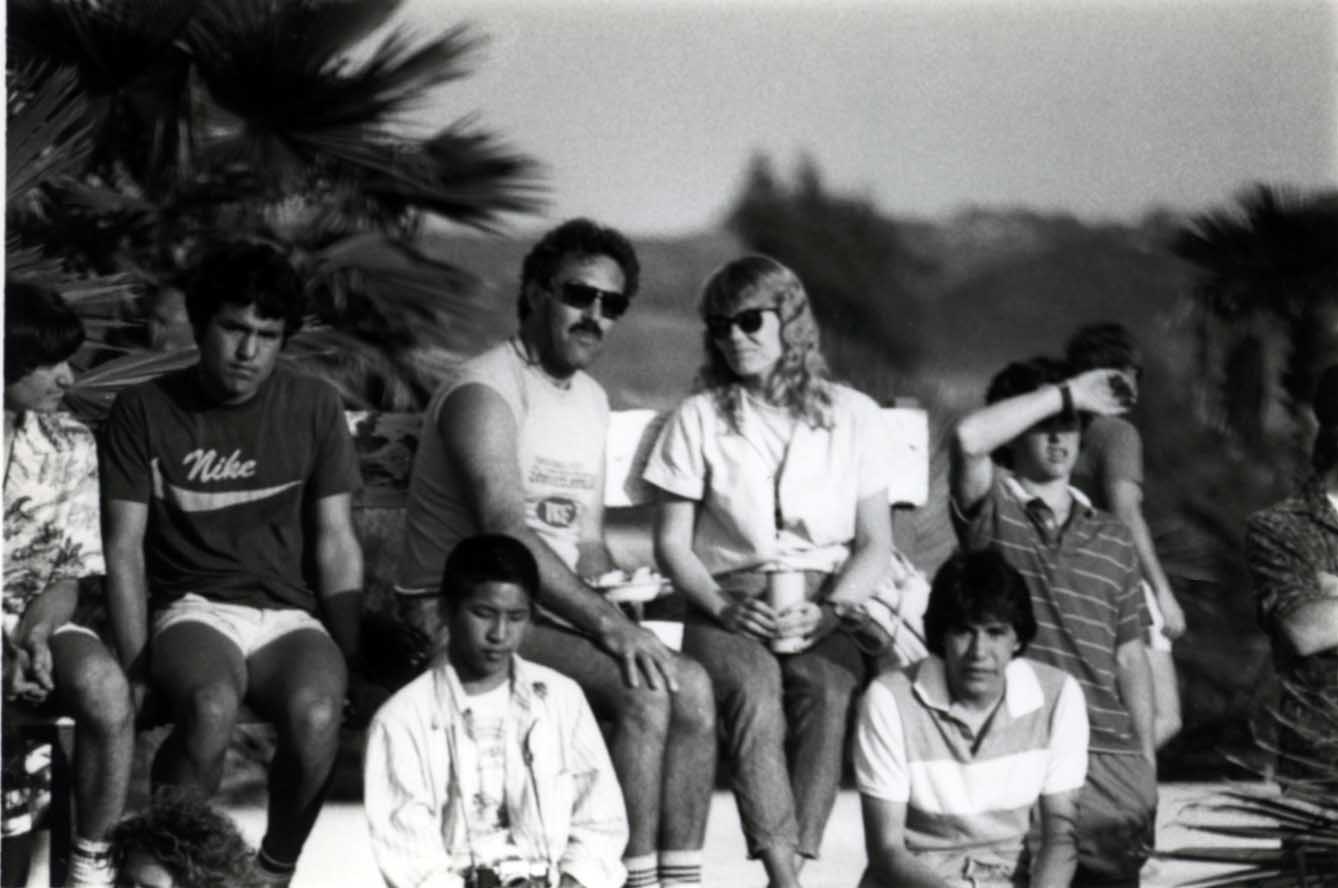

Tony Hawk, pro skater: When Transworld came, I was hyped that there was actually a magazine devoted to skateboarding. It felt like validation. I was stoked to be a big part of it. The pioneers of Transworld were the [legendary skatepark] Del Mar Skate Ranch crew, so to me it was like a really big family. It was Grant [Brittain], it was [Dave] Swift, Larry Balma, locals like [Tod] Swank. It was like, this is awesome, we still get to skate together and hang out.

Grant Brittain, writer, editor, and photographer, Transworld Skateboarding, 1983–2003: I started working at Del Mar Skate Ranch in ’78, and I knew Larry Balma through Tracker. In ’83 he asked if I wanted to give some photos to a newsletter they were working on. He wanted to start Transworld to kind of go against Thrasher and Independent Trucks, because Fausto [Vitello] owned Indy and Thrasher, and they didn’t like the direction that Thrasher was portraying skateboarding. “Skate and destroy” and all that.

Larry Balma: We wanted it to be a worldwide, international kind of name. Well, my corporation that I had with my fishing boat was Transworld Marine, and that just never dawned on me until our attorney said, “How about Transworld Skateboarding?”

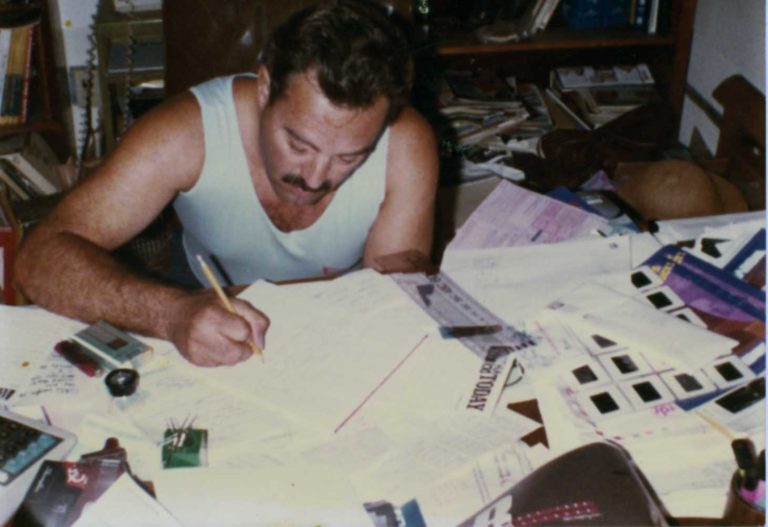

The first issue, Peggy and I put it together. She was doing the editing and I was figuring out the printing and all the pre-press stuff and everything. We’re working daytime doing Tracker and we’re working nighttime doing the magazine. The guys are sleeping at the company or sleeping at my house or whatever. It was crazy.

Tony Hawk: My dad shot the cover of the first magazine. It’s a picture of Steve Caballero, I think at Palmdale, and that was the last contest before the issue came out. I’m pretty sure I was in that issue—if not that one then the next one. Everything then was about contests. So it was pretty much guaranteed that if you placed well at a contest, you’re going to get a photo in the magazine.

Grant Brittain: It was heavily San Diego influenced at the time. There was always north vs. south, Indy vs. Tracker, San Francisco vs. San Diego. It was kind of friendly, but when I went up north to shoot, I’d get vibed because I was Transworld. They called us the slick, goody-goody mag and they were the punk mag. But everybody was the same pretty much. At a contest everybody was friends. I’d even hang out with guys from Thrasher.

Tony Hawk: In those days it became the best overall mainstream magazine because they could carry it in grocery stores and the content wasn’t so shocking to people. Thrasher, not that they were shocking, but they did get a little edgy and maybe turned some people off, like moms and dads—but that’s what skateboarding was. That’s why I appreciated both publications.

As skateboarding grew in the 1980s, so did the magazine.

GSD: In summer 1983, [pro skateboarders] Marty Jimenez and Bryan Ridgeway moved out from the Midwest and got jobs at Tracker and Transworld. We all slept on the floor in the upstairs offices for several months, until Larry grew tired of being greeted by slumbering bodies at work and gave everyone the boot. Earning minimum wage, I couldn’t afford to rent my own place, so I started sleeping at Del Mar Skate Ranch in the Hi-Balls (enclosed trampolines) or in the pools. The last bus down there from Tracker was at 9 p.m., and whenever I missed it I would be forced to play hide-and-go-sleep somewhere inside the Tracker building.

At first, it was in hidden corners, then behind strategically stacked boxes. After being busted and booted from there and everywhere else in the building, I was finally forced to take it to the outer limits. There was a ladder in the upstairs bathroom leading to the roof through a removable panel. In between the ceiling and the actual roof was a two-foot high space in the rafters, where a stray piece of plywood became my new bed. This set-up worked flawlessly for a while, and I went undetected. One morning, Larry Balma’s head suddenly popped up through the ceiling panel, only to solemnly announce, “You’re busted, GSD.” Supposedly, the clue that gave me away was a small crack in the ceiling.

Grant Brittain: I worked at [Del Mar Skate Ranch] til ’84, and then Larry took me on full-time. I was still only getting a few hundred bucks a month. I built a dark room at Transworld—I did all the photo work before that in the dark room at Palomar College. Then it just started to grow and grow. [Award-winning graphic designer] David Carson was art director, that was one of the first magazines he ever did. That brought us up to another level, where people started to take notice. The layouts got slicker.

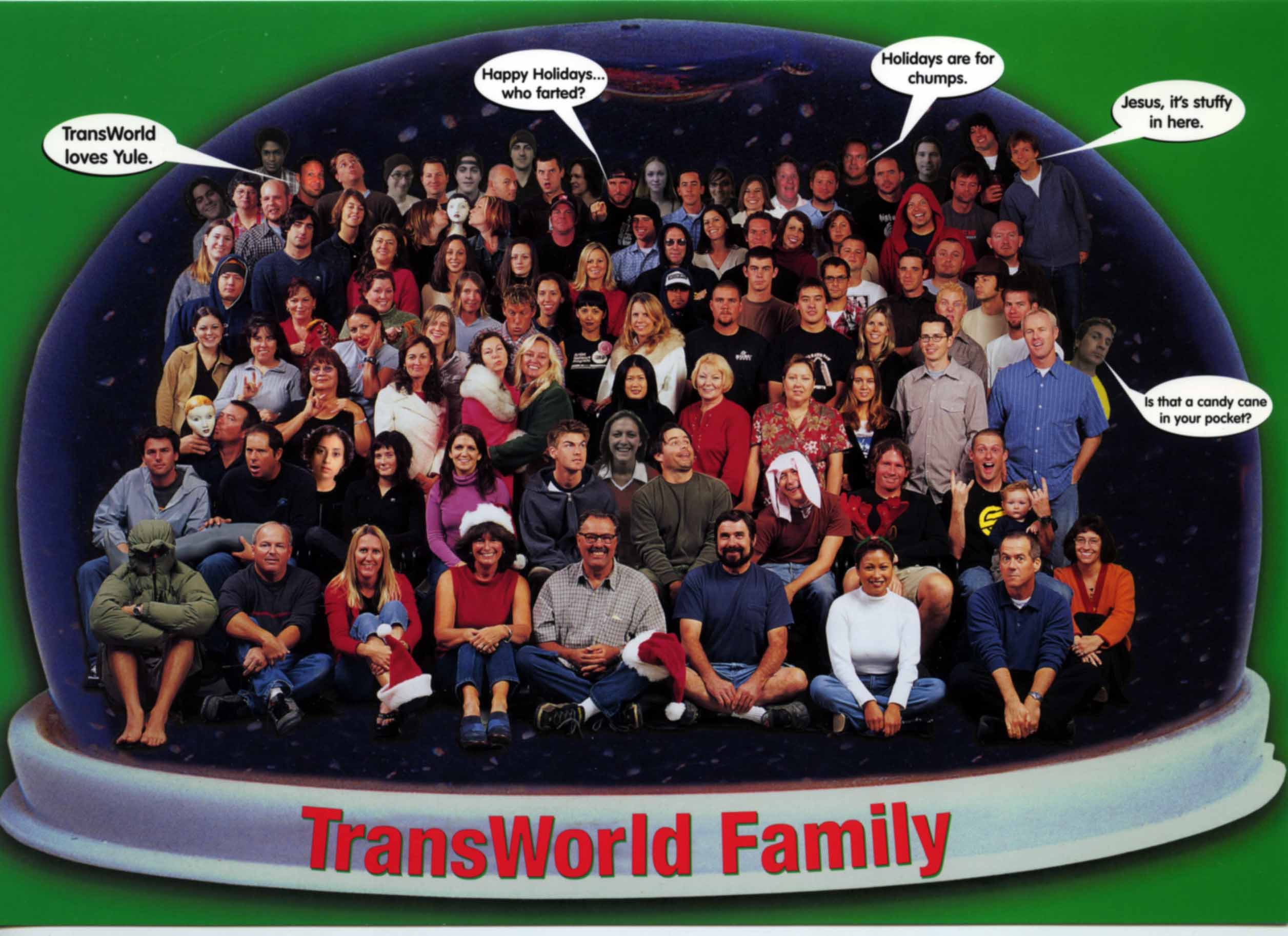

Peggy Cozens: One of the things that I think was so critical was that everybody felt like they were owners, like they were part of the whole picture. It was a synergy the way it developed over time. That was the best part, having all these fantastic, talented people come in and do their jobs. They loved it—we loved it.

Dave Swift, writer, photographer, and editor, Transworld Skateboarding, 1989–2003: I’d been a sponsored skater from ’84 to ’89. I was 24, the sponsored skating thing was getting a little tired. Being older, not being pro, kind of just living the skater’s dream, my parents were obviously pushing me to get on with my life. Which I obviously didn’t want to do. Somebody said that there were some openings at Transworld, and I was like, “Well, shit. Maybe I could do that.” I ended up getting a job as an assistant editor, and started working there on January 2, 1989.

That very first trip that I went on, and having that article printed in the magazine, was a real big deal for me. “Mom, look, I’m not as dumb as everybody thought.” At that time, people didn’t look at skateboarding as something you could do as a career, whether as a skateboarder or a photographer. It was just, “What are you doing that for? You’re too old.”

Grant Brittain: I was stoked for everybody, that they could make a living off of skateboarding. In the 80s when I was shooting photos, I didn’t do it to be a skate photographer. I was just shooting my friends at the park and skating and having a good time.

Despite the skate media ecosystem’s best efforts, another bust was inevitable. Case in point: In 1989, Tony Hawk could be seen on movie screens across the country alongside Christian Slater in the skate classic Gleaming the Cube. A few years later, Hawk was scrounging for “change underneath the floor mats of his Honda” so he could eat at Taco Bell.

Dave Swift: By about ’92, the skateboard industry had really taken a dip, and it seemed like there were far fewer people who actually rode skateboards. The legends from the 80s had all started skateboard companies, like Lance [Mountain] started The Firm and Tony Hawk started Birdhouse. The bigger companies, Vision and Powell, were all in financial turmoil. There wasn’t that much money in it at this point. You had to be pretty diehard to survive.

GSD: TWS went from skinny in 1983 to fat by ’87 and back to skinny again by the early-90s. If you put every issue of TWS on a shelf, you could, by looking at the spines, watch the skateboard industry, as well as the economy in general, wax and wane over the decades.

Tony Hawk: When everything stared shrinking, including my income, I chose to start a skateboard company, because I felt like my career as a skater was ending for the most part and that I still wanted to be in the industry. I think Per Welinder and I started Birdhouse with $40,000 each. Our very first expense was to advertise in Transworld. Transworld, for the back cover or the inside cover, was $500. We jumped on it, because we were like, if we’re going to make any kind of name for ourselves, that’s going to be the place to advertise. That was our way to tell people what we were doing and to announce our brand.

Big-name sponsors closed up shop, but the austerity period eventually passed. Vert superstars retired their contest pads and skateboarders stepped off of the backyard mini-ramp and into the streets. The “small wheels, big pants” generation emerged, codifying the style of skateboarding still dominant today.

Skin Phillips, photographer and editor, Transworld Skateboarding: I moved out to the States and got a job at Transworld in the spring of ’94. It was like a dream come true. We were there to document that rebirth of street skateboarding—it was just a good healthy time for skateboarding and the magazine.

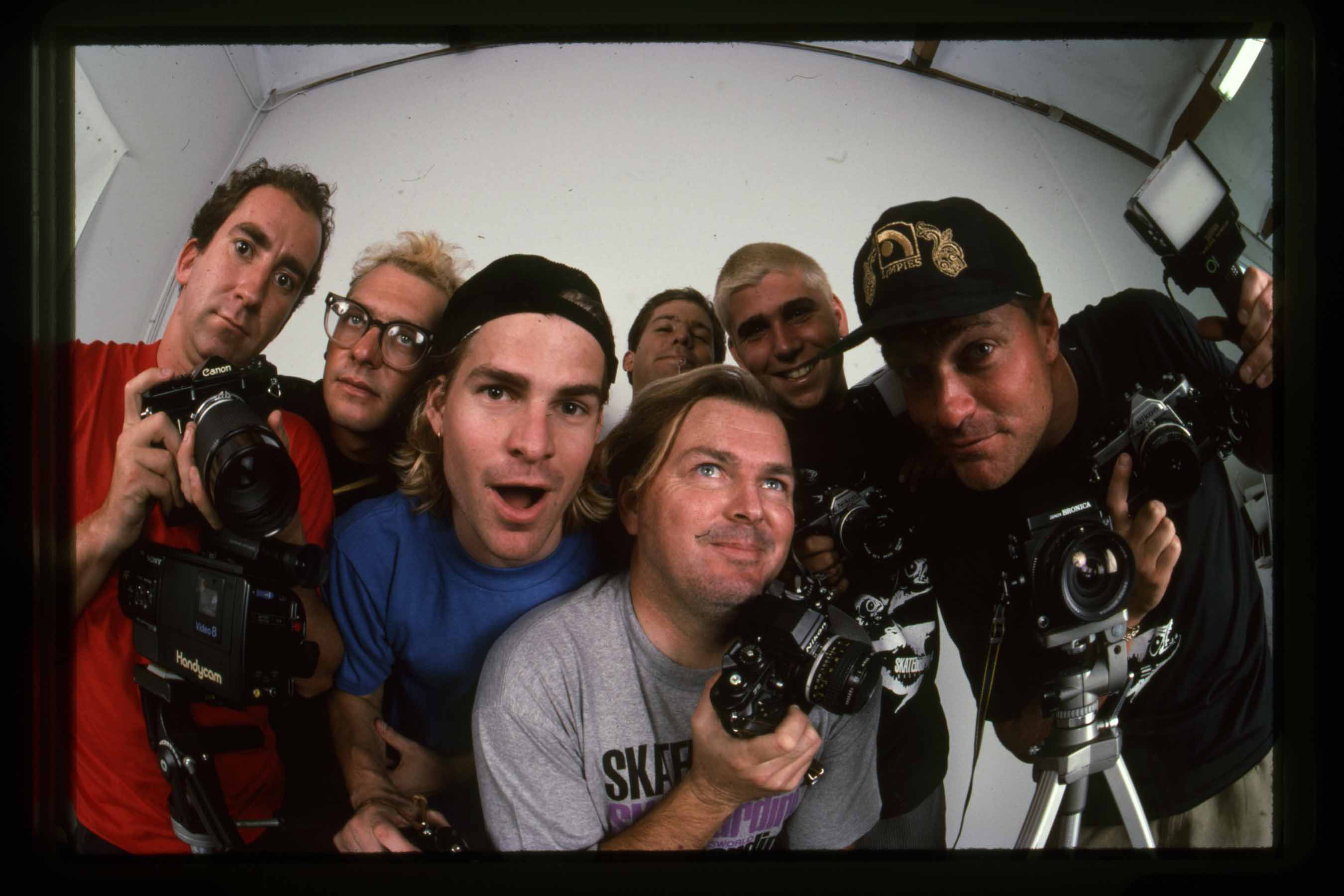

Grant Brittain: We’d sit around and make jokes and stuff would end up on the cover. “Oh, it’d be cool to do this.” “Well, why can’t we do that?”

Jamie Thomas, pro skateboarder: I basically hung out on the couch and befriended Swift and Grant and Skin. I gradually started getting invited on sessions and tried to make a good impression on those guys, because I knew that they were the gatekeepers to the magazine. But they were really cool guys, so it came about naturally.

I remember seeing a roof gap at Fallbrook High School and I brought Grant there and did a pop-shove and a kickflip across it. The kickflip was all rocket, like how kickflips in those times were, and I remember being super hyped on it. Then a month or two later I came into Transworld and they handed me the magazine and I was on the cover. It was mind-blowing.

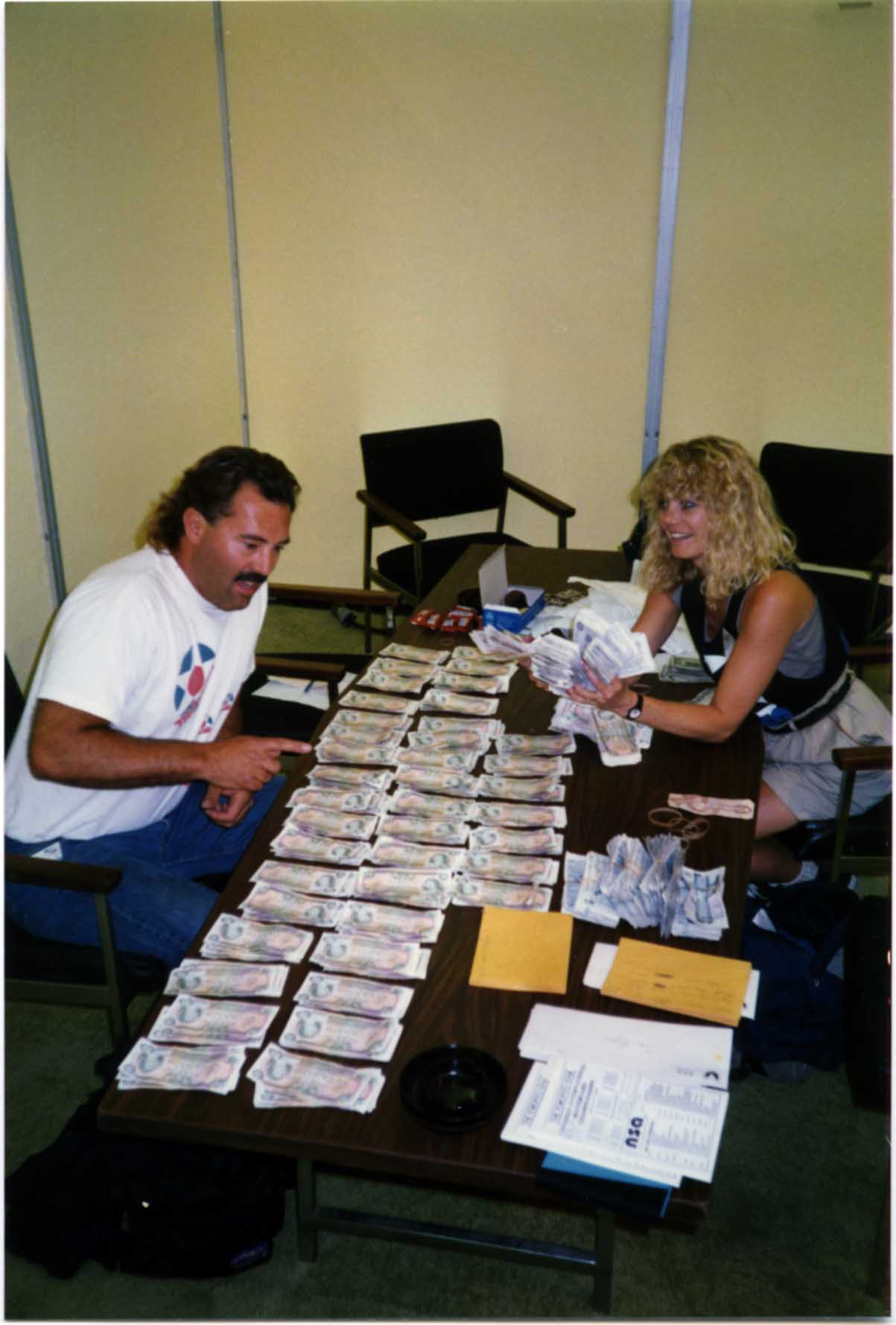

Dave Swift: Skateboarding started to grow from these fledgling companies. Sole Tech, Etnies, Emerica, DC Shoes—there were a lot of people who invested whatever they made as a skateboarder and threw it all into skateboarding. Which was really cool to me, how we as skateboarders really built this thing.

By 1999 it got really big. You’d notice magazines being 300 pages, and skateboarders were everywhere. The industry was thriving, with 100-something companies advertising in two or three magazines. Unheard of.

Jamie Thomas: There was a time in the late 90s and early 00s when it was definitely the biggest magazine with the broadest reach. If we wanted an article or ad to be seen, that was the place you had to have it. It was like two to three times the distribution of Thrasher. That’s what we were told—we didn’t really know—but you saw it everywhere. It was in every newsstand, every bookstore.

Greg Hunt, pro skateboarder; cinematographer, Transworld Skateboarding: When I worked there, the magazine itself was 400 pages. It looked like a Vogue or something. I’d never seen a skate magazine that thick. Videos like Sight Unseen and i.e., I think they were selling like 50,000 videos. That’s more than have been sold of a skate video in a long time.

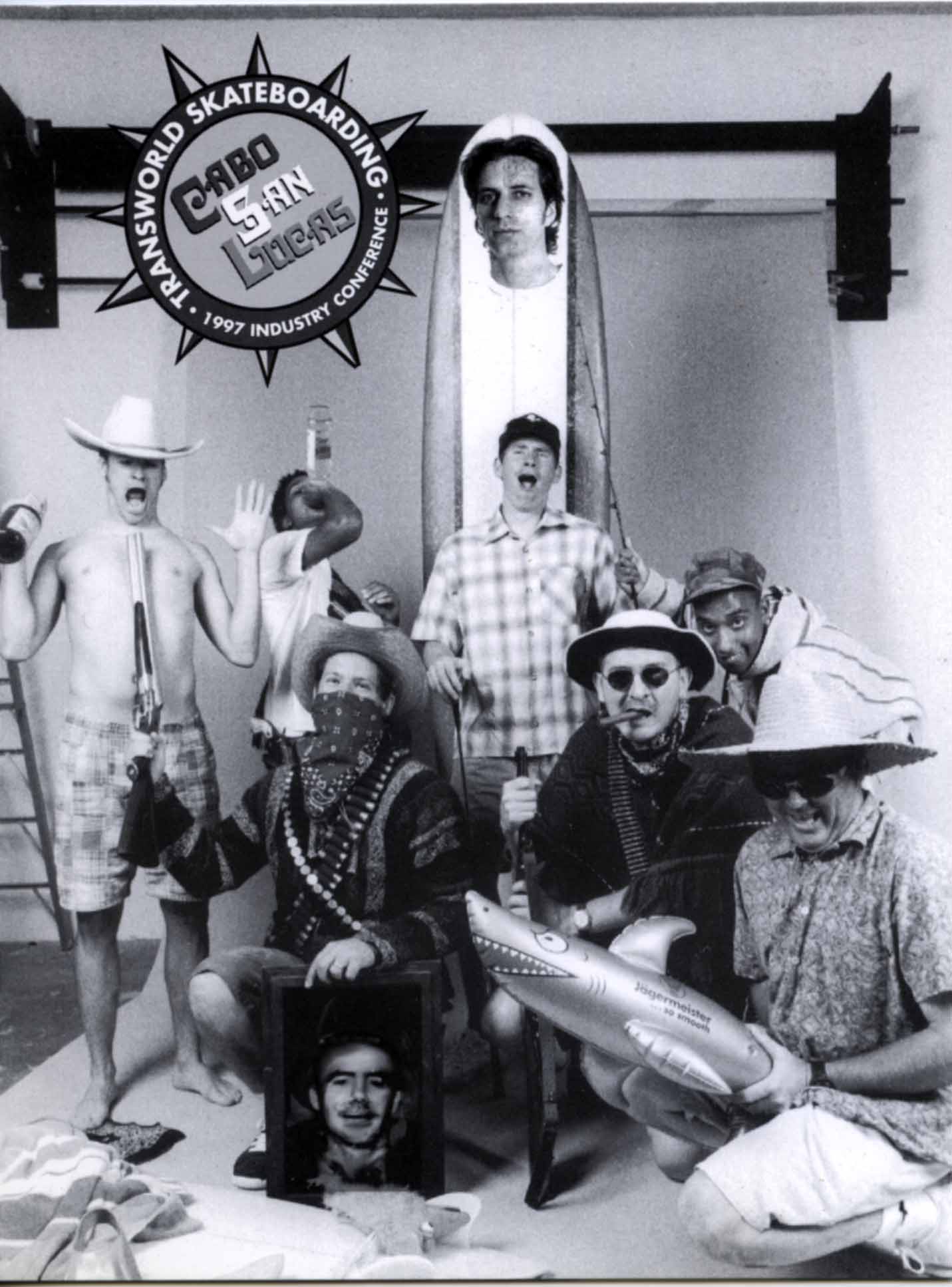

In the late 90s, Transworld Media, which by then included Transworld Snowboarding, Transworld Surf, and Ride BMX, was sold to Times Mirror, part of Tribune Media.

Larry Balma: We started talks in ’92, and I didn’t think we’d ever make a deal. That was just on Transworld Snowboarding. My basic deal was to string out Times Mirror as long as we could, and I had them sign a thing that they wouldn’t talk to anyone else. The other magazine was Snowboarder at the time, and if they couldn’t buy us they were going to buy Snowboarder, and then Snowboarder would have the finances to go blow themselves up. After a year they started listening to what I had to say. We were telling them that we had to do the magazine here. They’re going, “No, the way a magazine’s done is you go to 2 Park Avenue in New York and do your magazine out of the business building.” It took two years and we ended up doing a deal with them. They let us keep the magazine here in Oceanside and do the work on it. A year after that the guy who did the deal came down to Transworld, and he’s got four guys in the limo with him. I said, “What are you doing here?” He says, “We’re just trying to see how you guys can run so efficiently.” And I said, “One thing is we don’t haul four guys around in a limo to go figure that out.”

Dave Swift: Somebody would be like, it’s going to get corporate around here, and I was like, “What does that even mean? I’m getting a raise this year, sick.” We weren’t bothered by it. My staff was bigger, probably about ten people at that time. The people running the place still didn’t bother us.

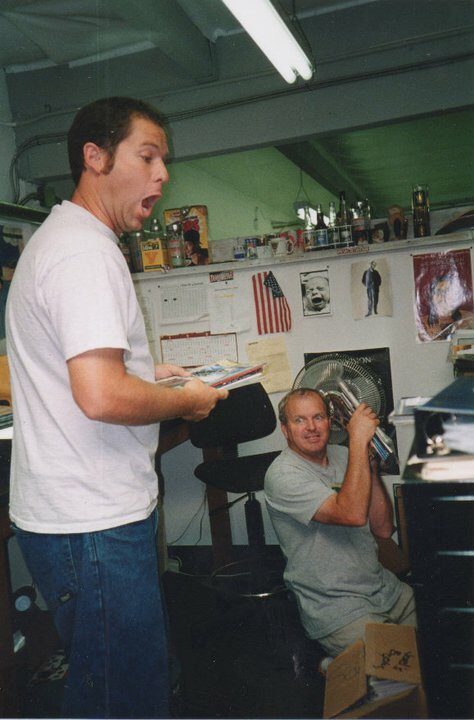

Greg Hunt: They’d been bought by someone, but it felt pretty independent. Everyone skated, everyone was cool. Dave Swift was technically our boss. We’d have budgets and stuff, but really he’d just come in and watch the video and be like, “Yeah it looks awesome.” It was so mellow. I’d live in that office and no one really seemed to mind. There was a little fold-out couch and I’d sleep there for like, three or four weeks. I was living there when 9/11 happened—I woke up in the morning and they evacuated the building. I was there a lot.

In 2000, Times Mirror was bought by Time Warner (soon to become AOL Time Warner) for $475 million.

Dave Swift: Times Mirror was fine. It went on for a couple of years and all of a sudden we’re bought by AOL Time Warner. That hit home a little more, that now we’re going to be really corporate. I had to go to the general manager to talk about budgets. We were spending probably $17,000 a month just on film by 2002. I talked to one of the ad guys in 2002, and he said I think we’re averaging about $1,000,000 an issue in advertising. Imagine that: A 400-page magazine—probably the average ad page is about $3,500—and they’re running 60% ads, 40% editorial. It was generating a lot of money.

Grant Brittain: They were running haircare products and Army/Navy ads, we didn’t have any say. We were like, at least we can keep the magazine pages up and have more skating in it. We tried to look at the good side of it. More pages, more skateboarding. Then the AOL disc got dropped into the magazine, by surprise—it was never run by us, because we probably would have flipped out. After that we just kind of went, this isn’t getting any better. We didn’t have as much control. We were trying to stay true to skateboarding, and people who didn’t skateboard didn’t care.

Peggy Cozens: I always said it was Harvard MBAs who thought they knew more than those of us in the trenches, and to this day I still believe they didn’t get it. They didn’t know the product, and they wanted to put Clairol in the front of the magazine and replace Santa Cruz on the back cover.

Jamie Thomas: When it got bought by some of those corporate machines, it started getting homogenized. They couldn’t do a lot of the things that made skateboarding cool and different. Thrasher had the edge—they’re independently owned—and they could do whatever they want. I feel like having milk ads and having Marines ads kind of set Transworld up for the gradual decline. I remember feeling kind of repulsed by them not saying no to any advertisers. When things get that blown out, usually there’s a pretty big backlash to it.

Dissatisfied with the new ownership, Grant Brittain, Dave Swift, Atiba Jefferson, and other TWS employees left to start The Skateboard Mag in 2003.

Dave Swift: In January 2003, 25 or 30 people [from throughout Transworld Media] got laid off. All at once, all in one room. It was really weird, there was no emotion as far as how they got laid off. Just, “Sorry, here’s your six months severance, adios.” To me that was weird, but to Grant it resonated more. He was like, “This is going to happen to me.” I was like, “There’s no way. We’re still growing. Why would you think anything’s ever going to change?” But then one of the ad guys, I think a few of his contemporaries got laid off, and he had a new boss pushing him to sell more for less commission, so he started going, “We should start our own magazine.” That kind of steamrolled into, “Let’s just do it.” Our first issue, I think we made $230,000 in ad revenue. From 2004 to 2008, it was peaches. I think there was a point in 2008 when the skate industry started contracting big time. Especially the shoe end. You had Sole Tech going from $28,000 an issue to $12,000, overnight pretty much.

After we left, it left this void, and it kind of split up San Diego as a media place. It put two magazines in one zone. Zero and all these companies that were down here had to choose where to put their money.

Jamie Thomas: I had my friends at The Skateboard Mag, and Transworld still had the biggest distribution, but after they left it became somewhat the softest mag. Then Thrasher had a limited distribution, but every single issue was consistently amazing. You were definitely torn in how to do it. All I did was alternate. Just try to grease the wheels, keep all the relationships rolling.

Following the Skateboard Mag exodus, several editors from long-running rival Skateboarder joined Transworld Skateboarding. Just as its staff was in flux, so too was Transworld’s ownership. The company was bought by Bonnier Corporation in 2007; in 2013, GrindMedia, which published Skateboarder, acquired Transworld from Bonnier. They shut down Skateboarder in 2013, at which point its former editor-in-chief Jaime Owens took the same position at TWS.

Jaime Owens, editor-in-chief, Transworld Skateboarding, 2013–present: I think when I got here in 2013, that was kind of the last hoorah of all the glory days of Transworld. It started dwindling and dwindling. People didn’t have the money, and a lot of times if they did have the money they were going to Thrasher.

Mackenzie Eisenhour, writer and editor, Transworld Skateboarding, 2005–2019: As far as my experience with it, there’s always been ownership somewhere and it’s always been dicey. I fell in love with Transworld, I discovered skateboarding through Transworld, so there was this romantic side of it that I tried to keep away from the uglier side of it being owned by all these corporate vultures.

Jaime Owens: People always have the perception that Transworld was owned by big corporations through the years, but you knew that the people making it were die-hard skateboarders. There’s a bunch of bullshit all around us but the nucleus of this is people who grew up loving skating.

We really focused to get the brand back on track, to make it respected within the industry, and I feel like we accomplished that with the magazine, and with the video—we were able to put out Duets this year. But it was probably too late—it’s just the industry itself.

It’s definitely in a downturn. There used to be five magazines, and there were brands that were advertising in all the magazines every month. That’s crazy to think: There was Skateboarder, Big Brother, Slap, Thrasher, The Skateboard Mag, Transworld, and Enjoi skateboards advertising in all of them every month. That was thousands of dollars for each of those mags. Those days are long gone.

Early this year, following months of rumors about Transworld’s future, AMI bought TEN’s Action Sports Network, which included a total of 14 brands. Multiple titles were shuttered, including Transworld Snowboarding. People lost their jobs, and it was announced that Transworld Skateboarding would no longer be printed.

Mackenzie Eisenhour: I got a heads up in November that they were looking to sell. I don’t know exactly when AMI and the National Enquirer came into the picture, but once that was announced obviously we were all super bummed. None of us are big fans of their media company. I can say that. I’m not employed by them.

Jaime Owens: The past few months have been such a weird gut punch, I’m like super disoriented in the realm of what’s going on and still trying to wrap my head around the future.

Early one week, late in January, they told us everybody’s gotta be in the building Thursday and Friday. If you’re on a trip, come back. We were like, that just means they’re going to tell us that we’re sold. That Thursday some people got an email that sent them to one part of the building for a meeting, and other people went to another part of the building. Then they laid off a bunch of people—I was in the other meeting. Then Friday David Pecker came into the skatepark [in the office, where they make videos for the website] and told us welcome to the company, we’re AMI, and here’s what we do, etc. In the middle of that meeting he’s like, OK, from here on out these are the three brands that are still going to be in print.* And named off Surfer, Powder, and Bike. And I just was like, “Holy shit, all right. Wow.” I’d already been punched in the gut the previous day when four of our staff people got laid off, so I was still reeling from that.

Peggy Cozens: You can always look back in hindsight about selling. I’ve had my times of going, “Dang, why did we do that?” It breaks my heart in some ways that we did. It was OK when Times Mirror owned us, they were fantastic. But you don’t always project into the future what the future’s going to be. We didn’t know; let’s face it. Going from the most soulful skateboarding magazine, reflecting the creativity and talents of these skaters, with the best people as staff, to having someone like American Media take it over is just beyond me. Never in my wildest dreams would I have anticipated that.

Mackenzie Eisenhour: I’m just super grateful that I got to work there. I just want to say thanks to all the fellow employees. It definitely was an amazing experience. It’s a tough thing to keep going. There’s not really any print magazine that’s killing it, even in the mainstream. If anything I think it’s amazing that it went as long as it did.

Tony Hawk: Honestly, that happened slower than I expected, just with the advent of social media. Online publications, online coverage, live coverage—who wants to read about an event that you saw online a month ago? I’m not surprised by that, it was surprising more to me that it took this long to really feel the pinch of that.

Grant Brittain: My son’s 24, he’s been skating all his life. I’d bring the magazine home and I’d set it on the kitchen table and it would sit there for three days. He’s not looking at it, and he skates every day.

Skin Phillips: I just used to look at those photos—it’s hard to explain to kids now what that meant. What that feeling was like when you got a magazine, or when you’d hear a record for the first time and you could only play it on vinyl in your room. I think that’s just a part that has died. It’s just a feeling you can’t get anymore, because you see it every day, every minute.

Dave Swift: All I can say is it was a great experience working at Transworld. We all had autonomy as skateboarders. Everybody who worked for me came from skateboarding. I don’t think anybody who worked for me had a college degree.

Peggy Cozens: I always felt like I was a fish out of water being the female. There weren’t a whole lot of women in this industry. It was hard at times, but I still persevered. It was out of my love for everybody—the sport and the kids—that I even got involved. I’m grateful for the experience. I still say it was the best time in my life.

Larry Balma: For me and Peggy, the magazine was kind of like our child. You raise your kids and tell them, “This is good and this is bad,” and they leave home and carve out their life. I don’t know if it was a smart thing to completely cut off the print, but that’s the way things are going. I have a couple magazines that I look at on my stupid phone.

Jaime Owens: With everyone on Instagram saying “Transworld’s dead,” we were like, “Technically we’re not.” Our sales guy said it was like being a ghost at our own funeral and watching everybody pay tribute.

Transworld’s audience is the biggest it’s ever been. We have over four million people who we reach on a monthly basis through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, all that. We have budgets to make stuff this year, so there’s still a great opportunity to do cool stuff and get it out to a large audience.

People like to romanticize things, but were the majority of people buying the actual magazine? I doubt it. Did they have subscriptions? I doubt it. I accept that Instagram is where a lot of kids see stuff, and I want them to see it.

Grant Brittain: I started thinking about all the families that magazine supported over those 36 years. All the people whose careers got started because of that magazine. All the time people tell me, “The photos in that magazine made me become a photographer.” It has such an impact on a lot of people.

Jamie Thomas: They gave me an amazing opportunity. I can’t thank the dudes enough for helping me and helping my career and all the good times we shared in those early days. For me those memories are priceless.

Tony Hawk: No matter what, I always made time for Transworld—that’s the bottom line. If they requested something of me, I would always cancel other things or make sure I had time to do what they wanted. I owed them a lot.

Dave Swift: The only survivor of this whole mess of skateboard media is Thrasher. And why? Because they’re still owned by a skateboard family. Skateboarding being a very cyclical business—which it has been for the last 40 years—you better have that stick-with-it-ness. Fausto’s values are what keeps that company alive. If I ever were to start another magazine, that’s how I would do it.

Skin Phillips: God knows what would have happened to professional skateboarding if it wasn’t for Thrasher and Transworld. It’s a scary thought.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

*An American Media spokesperson provided VICE with the following statement:

“American Media was excited to step up and invest in these brands and employees, ensuring much of the staff and the company’s office maintained their California presence.

“While the vast majority of the brands’ audience engages via digital platforms, we have maintained a regular print frequency for Surfer, Powder, Bike and Snowboarder, and other brands will continue to be made available as special issues throughout the year. The company remains incredibly confident in its investment in all of the Adventure Sports Network (ASN) brands and the events business which includes the continued management of the Dew Tour Skate + Snow events.”

Follow Hanson O’Haver on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.