Ask a Lawyer: Can Hotels Really Deny Entrance to Rappers?

Credit to Author: Jessica Meiselman| Date: Wed, 29 May 2019 17:57:57 +0000

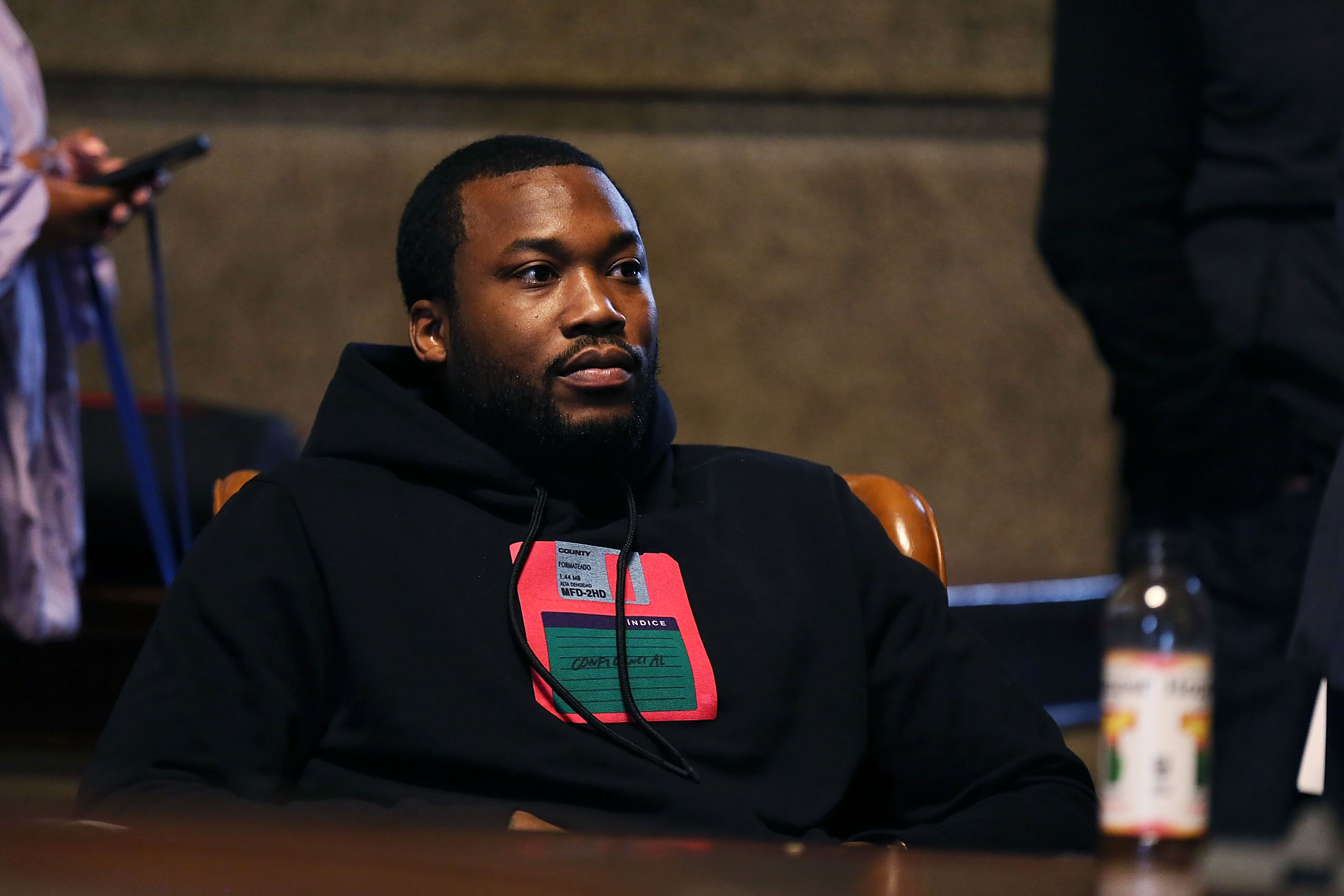

In a series of videos posted to Twitter on Monday, Meek Mill documented a Las Vegas hotel refusing him entry to the premises without much explanation. Meek alleges the refusal constitutes race-based discrimination and is evidence of a pattern of conduct by Las Vegas hotels: ”Vegas [is] notorious for this too, its not just me.” The videos show Meek leaning out of a car repeatedly asking a security guard at the Cosmopolitan Hotel why he is being denied entry, to which the staffer states “we are a private property—at this time, given the information we have, we are refusing to do business with you, we have the right to do that.” The guard continues to tell Meek that if he does not leave, he will be arrested for trespassing.

The Cosmopolitan released a statement much later, stating that they were at capacity and Meek’s refusal had nothing to do with his race or status. Meek has since engaged an attorney who released the following statement in response: “The assertion that the Cosmopolitan denied Meek because of capacity concerns at Marquee Dayclub is outright false. In the recorded video, Meek also inquired about getting a meal at one of the hotel’s restaurants, yet their security team continued to deny Meek and said he would be arrested for trespassing regardless of location in the hotel premises. The Cosmopolitan’s conduct continues to be deplorable.”

Meek’s attorney is vowing to sue the hotel for discrimination and defamation over the altercation. He also alleges that the hotel’s conduct on Monday is just one event in a pattern of discriminatory conduct; specifically, that the hotel has a formal list of rappers who are not permitted entry, including Blocboy JB and Yo Gotti. Last night, Yo Gotti weighed in on the situation, telling TMZ “he has experienced similar discrimination at the Cosmopolitan, and other hotels in Vegas.”

But what can one make of the security guard’s insistence that as a private property, the Cosmopolitan has the right to refuse “to do business” with individuals? Technically, he’s right, but the hotel cannot base their refusal on specific categories protected under law, such a race and gender. If indeed the Cosmopolitan’s door policy is grounded in racial preferences, or—even if that isn’t the case—if their policy disproportionately affects people of a specific race, it could be against applicable civil rights laws.

Door policies at nightclubs have long been the subject of discrimination cases. The combination of one person having total decisionmaking power, plus the lack of transparency why someone has been rejected can easily hide improper motives—or sow confusion, even if there is a legitimate motive. That being said, it is no surprise that door policies that require decisions to be made about potential guests relying only on their appearance often manifest problematic results.

So, if Meek decides to file a case like this, what will it look like and what does he need to prove? The entire United States is subject to the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits in part “discrimination [on the basis of race] by privately owned places of public accommodation.” The act provides examples of places of public accommodation—including hotels, restaurants, and places where entertainment is offered to consumers. The Civil Rights Act permits the US Attorney General to look into establishments accused of violating the act and potentially bring a civil action in district court against them. Given the ambiguity around nightclub refusals, and the obvious other priorities of Trump’s Justice Department, it’s not likely that we’ll see this kind of investigation.

However, many states, including Nevada, have implemented their own civil rights statutes that go further than the federal legislation. Unlike the federal legislation, Nevada’s civil rights statute allows a person to pursue “actual damages” in which the infringement of civil rights occurred. Actual damages would have to be proven, and do not include “punitive damages,” which would resemble a penalty. Other remedies could include a court order for the business to cease discrimination and reimburse a plaintiff for attorney’s fees and costs.

In order to make a successful claim for discrimination, Meek would have to prove that there were discriminatory motives behind the Cosmopolitan’s door policy. Although perhaps relying on his denial alone would be insufficient—if indeed other similarly situated Black artists have been treated comparably—he may be more successful in showing a formal policy behind the pattern.

Meek’s lawyer also claims an intention to sue the Cosmopolitan for defamation. In Nevada, defamation can be claimed when a defendant negligently or recklessly “publishes” a false statement about an individual, and such publication leads to a damaged reputation. Although “publication” is not limited to written publication, the scenario at hand doesn’t appear to suggest any specific false statement was made that subsequently damaged Meek’s reputation.

The most likely scenario is that this will fizzle on the legal front—a discrimination claim would be an uphill battle with little monetary upside and a defamation case would be similarly inconsequential. However, on the public relations front, more attention to this kind of behaviour and treatment could fuel actual change. This wouldn’t be Meek Mill’s first foray into civil rights activism—after facing multiple years of incarceration for minor probation violations, he become a spokesperson for prison reform. Attention to actual injustice from a figure like him or other artists has the potential to influence local legislative priorities and priorities of private businesses as well.

Jessica Meiselman is a lawyer and writer based in New York. Follow her on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.