Enter Thrash Zone, a Japanese Metal Bar Where ‘Extreme Beer’ Is Everything

Credit to Author: Hilary Pollack| Date: Wed, 29 May 2019 12:20:36 +0000

A particular kind of thrill-seeking kid will find catharsis for their adolescent angst in the opening notes of Metallica’s 1984 album Ride the Lightning. Koichi Katsuki found the rest of his life.

Like many other teenagers in the 1980s, Koichi got into heavy metal when his friends started passing around albums emblazoned with images of skeletons, spikes, leather, and mullets. In Japan, where Koichi grew up, you could rent records from local shops for 200 or 300 yen a piece—a tenth the cost of buying your own copies. While the forlorn ballads of Yosui Inoue and the jazzy yacht rock of Akira Terao topped the Japanese charts, he’d whirl through Iron Maiden’s Killers and Judas Priest’s Screaming for Vengeance, then dig deeper in the bins for heavier riffs, deeper wails, and more epic stories of hell, monsters, and war.

“I need more, ah… intense,” Koichi recalled as I sat across from him at the bar of Thrash Zone, his brewery and bar in Yokohama, a bustling port city just south of Tokyo. “More faster, heavier. And then finally, I met Metallica.”

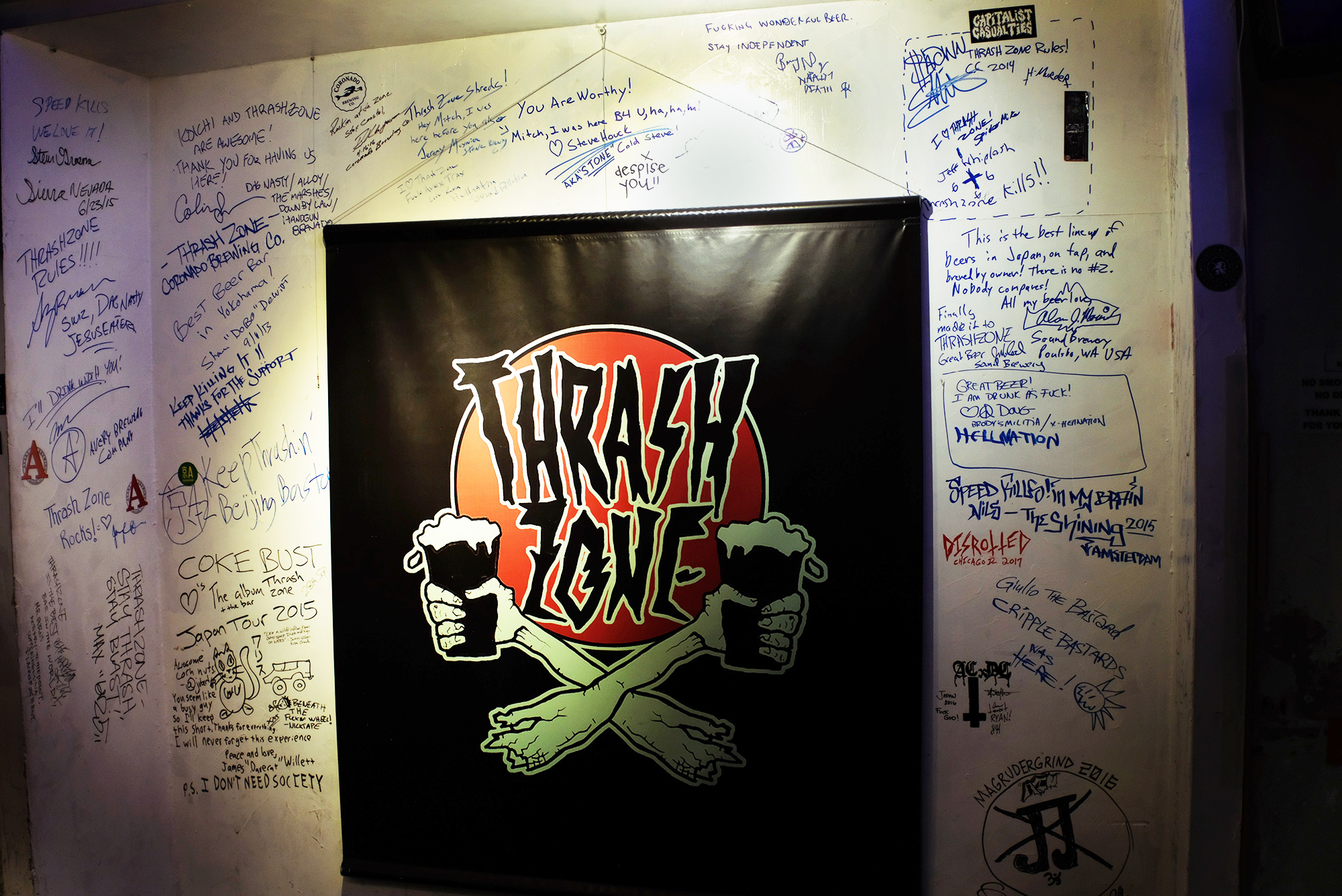

Koichi’s taste in music is echoed by his taste in beer. Thrash Zone’s slogan is everywhere: EXTREME BEER ONLY. The bar is tricky to find, a bona fide hole in the wall in a residential area of the city, marked only by a small hanging sign and a Marshall amp by the door.

Named for D.R.I.’s seminal 1989 album, Thrash Zone is a beer bar, but it’s also a shrine to heavy music. One wall is covered in old Xeroxed flyers for punk and metal shows, and the fonts and images on the signs, glasses, and coasters are pulled from Black Flag and Bad Brains. The back wall is built to resemble a stack of amps; its shelves are lined with hundreds of records, and with DVDs like American Hardcore and Slayer: Live in Montreux. Like a giant plaster cast turned inside out, the interior of the bar is emblazoned with hundreds of hand-scrawled notes and drawings from touring bands that have stopped by for the beer, the blast beats, or both—as well as tags from brewers at craft beer empires like Ballast Point and Coronado. (Sample entry: “FUCKING WONDERFUL BEER. STAY INDEPENDENT,” scribbled by Napalm Death’s Barney Greenway.)

Thrash Zone doesn’t serve just any beer; it’s a shrine to the bitterest and most brutal brews out there. Their flavors can be as malty and rich as a mouthful of cocoa powder, or so hoppy they taste like smoking a blunt, or so tart and grassy that taking a sip is like chewing a leaf just picked off a lemon tree.

When I dropped in, there were 14 beers on tap; eight were Thrash Zone’s own brews, with names like Speed Kills, Hop Slave, and World Downfall Stout. They’re made at a nearby facility and only sold here (and at Thrash Zone’s other location, which is a few miles away and also serves meatballs). Most are 7 to 10 percent ABV; one barley wine, Aru-Chu Ale, is 13 percent. Japanese pilsners tend to be about 5 percent, so a pint of these brews will get you two to three times as drunk as a mug of Sapporo. And while India pale ales typically clock in around 60 IBUs, or International Bitterness Units, most that Koichi serves are over 100.

This might seem like a pretty simple story: Kid hears heavy metal; kid loves heavy metal; kid becomes man; man finds out he likes beer; man starts heavy metal brewery. But Koichi’s path to Thrash Zone could only be manifested through true obsession. One of his, as you know by now, is very loud, very heavy music. The other is wild beers. And to bring Thrash Zone to life, Koichi had to make sacrifices and blaze trails where none existed.

In the States, craft breweries with punk rock leanings aren’t difficult to come by. But by Japanese standards, Koichi isn’t hyperbolic in calling his beers extreme; craft beer is relatively niche in Japan, with sales accounting for just 2 percent of the overall market as of 2018. Craft beer bars are becoming increasingly common in Japan, but are few and far between even in large cities like Tokyo; when Koichi opened Thrash Zone in 2006, beers like this were near-impossible to find.

“At the time, in the 80s [and early 90s], this kind of culture [was] obviously [for] the outlaw, or like the anti-mainstream,” he explained. “Outsider. Angry.”

Dressed in a turtleneck, wire-rim glasses, and a knit hat—no black leather jacket or mohawk, though his long hair signals alternative leanings—he reads mellow and polite, professional and unimposing, even shy. You wouldn’t necessarily guess that this guy was in a punk band called Ministry of Ignorance for 10 years. (He also played in Dictator, and currently performs in Marubellmen.) As I sipped a red ale that tasts like cardamom and the smell of my chain-smoking grandmother’s wallpaper (in a good way), Koichi told me about his path to Thrash Zone.

When he went off to university, Koichi started playing in punk bands. This was the early 90s, long before experimental Japanese rock acts like Boris, Merzbow, and Boredoms broke the collective cultural consciousness, and he soon found that making a living off heavy music was next to impossible. “At the time, in the 80s [and early 90s], this kind of culture [was] obviously [for] the outlaw, or like the anti-mainstream,” he explained. “Outsider. Angry.”

By 1995, Koichi found himself dragged into Japan’s salaryman culture, with its grueling suit-and-tie work ethic. Pulled from his greatest passion by the pressure to seek financial success, he took a job at Nippon Oil, a “big, big,” “very conservative” oil company in the coastal city of Osaka, and quickly realized that his appreciation for face-melting riffs was not going to be a valuable asset. “The role was not my real self,” he sighed. “Like a secret.”

While his 11 years at the company brought him little gratification, there was one bright spot in the job: its close proximity to a beer bar. As fate would have it, this wasn’t just any other pub where businessmen blew off steam with a couple rounds of Asahi. It was Minoh, a brewery that pioneered the early craft beer scene in Japan.

In Japan, roughly 95 percent of beer sold is pilsner-style lagers. The Big Four reign supreme, and government policy enables them to tightly maintain their control of the market. Microbreweries weren’t even legal in Japan until 1994, and the first boom of craft brewers struggled to break through a byzantine licensing process and a closed-minded public. The mouthy, bitter craft beer flavors that had been popular in the States for years were considered challenging compared to familiar, smooth-drinking pilsners. Minoh, which launched in 1997, didn’t shy away from fuller-bodied varieties like dark lagers and stouts. It was also run by a female brewer, a rarity in Japan to this day.

In 2006, Koichi ditched his job with a dream of starting his own beer bar. From its conception, the idea was to serve craft beer—none of that mainstream crap. He chose Yokohama for a location because despite it being the second-largest city in Japan, with a population of nearly 4 million, there wasn’t a single craft beer bar in town.

Andrew Balmuth is the founder and COO of Nagano Trading Company, one of the first distributors to help Koichi import those “extreme” American beers to Japan, and subsequently, to Thrash Zone. They met in 2006, shortly after Koichi left his salaryman job, and have been working together for over a decade. It was Balmuth who helped Koichi find many of the super-flavorful, outside-the-box beers he wanted to serve (and, of course, drink).

“Everything about his beer is like [his] music, and so his beers had to be extreme IPAs.”

“Those kind of intense, high-flavor, high-alcohol IPAs were very, very rare in the market,” Balmuth told me over the phone from his office in Yokohama. “Everything about his beer is like [his] music, and so his beers had to be extreme IPAs.”

In its first few years, Thrash Zone served whatever “extreme” beer Koichi could get his hands on. But soon, he caught the brewing bug himself. Waiting for his imported beers proved tedious; the journey from the US to Japan is by ship, and takes weeks. “I thought that we need more fresh, more high-level. And at the same time, I can adjust the taste,” he says. “So that’s why I started [brewing] on my own.”

Through a little resourcefulness and ingenuity—Koichi purchased his steel tanks second-hand through online auctions, and built most of the equipment himself—he fashioned a rig for half the cost that most brewers spend. “At that time, the average cost to open a brewery was around 100,000,000 yen (US $1,000,000). But as I studied about brewing, I noticed that [a] simple system was enough to [build a] small-scale brewery,” he says. In 2009, he applied for a brewing license, and finally received one two years later.

While he waited, he crossed the ocean to the veritable Oz of experimental brewing: California. He visited the craft breweries that were popping up like wildflowers there: Sierra Nevada, Bear Republic, Coronado, Ballast Point; he surveilled the coast and hit the Bay Area, San Diego, and Portland, trying every beer he could. His favorites were the super-bitter, freakishly hoppy ones—the pale ales and double pale ales, beers that were a little hard to take compared to what most of his peers grew up drinking.

The feeling Koichi got from drinking West Coast IPAs reminded him of his reaction to another California export: Metallica.

“That’s it! Just like Metallica!,” he remembered thinking. “The beer of Metallica. The Metallica of beer.”

When he was finally cleared to start producing his own beer in 2011, it was that boldness that he strove to emulate. Ry Beville—the founder and publisher of Japan Beer Times, a quarterly bilingual beer magazine—remembers the infancy of Thrash Zone, and of Koichi’s brewing style, as subversive and exciting.

“It was the early days of craft beer in Japan,” Beville told me from his current home in California. “It was way outside the box, back then, and even now. His place was famous as being one of the only places you could go to drink those beers.”

Koichi’s first beer was Hop Slave, an Imperial double IPA and a collaboration with a brewery called Atsugi. As Koichi once told the JBT, “Brewing a double IPA as your first beer is the equivalent of learning death metal in your first guitar lesson.” Hop Slave has been described as tasting “resinous” and “piney”—like “an outstanding citrus hop bomb” or a punch of marmalade, resin, and skunk.

The beer that Koichi was making didn’t just stand out for being hoppy and bitter; it was also a nod to the West Coast IPA boom that flourished in the 90s. “They’re kind of like throwbacks to 15, 20 years ago—they seem kind of old school, but it works,” said Beville. “Even other brewers from America that visit are like, ‘This is crazy… and it’s great!’ I don’t know of any other brewery quite like him in Japan. There’s something kind of punk about the brewing style.”

Thrash Zone isn’t meant for everyone. Touring musicians and beer connoisseurs are frequent visitors, but white collared shirts aren’t uncommon on weeknights—locals, as the rules say, are the most important customers.

“If my life is the anti-mainstream style life, the sacrifice will be money,” Koichi explained with a shrug.

Really, though, Koichi wants it to be a hub for local music nerds and beer obsessives who need a safe haven to listen to screaming guitar gods and drink brews so hoppy they taste like old coffee and wet matchbooks, or so sour they conjure pineapple juice and expensive vinegar. Should you wish to partake, you will have to play by the rules of Thrash Zone, which are found on both its walls and in English on its website, which is currently down. (Koichi’s been meaning to get it back up, but says he’s “not good at these kinds of things.”)

1) DO IT by YOURSELF = D.I.Y.

2) ANTI MAIN STREAM ATTITUDE

3) LOCAL PRIORITY POLICY

Koichi sees plenty of parallels between punk rock and beer brewing: the camaraderie between breweries, similar to that of touring bands; the strong DIY ethos; the respect for others in the game. And there’s the shared emphasis on art over profit. Koichi keeps prices low—almost shockingly low, considering he uses large quantities of hops and malt in his brewing process, neither of which are cheap. Balmuth also notes that Koichi will never add a beer to the taps just because it might sell well: “He chooses beers based on his own underwriting, his own criteria, his way.”

Koichi may be dignified, even gentlemanly, but he’s not big on compromise. “If my life is the anti-mainstream style life, the sacrifice will be money,” he explained with a shrug. But he’s made other sacrifices, too. Like many people in Japan, Koichi, now in his late 40s, has forgone the traditional trappings of adulthood—marriage, children—to focus on his passions. According to the CIA World Factbook, the median age in Japan is 46, and the Japanese welfare ministry predicts that by 2035, more than a quarter of Japan’s male population will have forgone marriage in their childbearing years.

But for someone who listens to heavy metal and hardcore all day, Koichi seems zen as hell. (The beer might help.) There is one thing that clearly ticks him off: While he may idolize the West Coast craft beer scene, he is not keen on how craft beer has become big business in the States, and is wary about brewers leveraging that counterculture to turn a profit.

“Beer is belonging in the subculture scene,” he told me emphatically. “The music, the beer—beer is subculture. They are doing, how do I say… just for money? Or just for, ‘Oh, this is fancy?’”

“Ah, trendy. Posers,” I replied.

“Posers! Yes!” Koichi shouted with a belly laugh.

Recently, he fulfilled one of his dreams by teaming up with the beer-themed powerviolence supergroup Trappist for a “beer and hardcore punk tour,” for which Thrash Zone made a beer (called Shout at the Duvel) to serve at the band’s Japanese shows. “For me, this was [a] big experience,” he told me in a recent email. “Like my dream comes true.”

Chris Dodge, the singer and bassist of Trappist, moonlights as a beer columnist for Decibel (his column is titled “No Corporate Beer”) and has also played in legendary hardcore acts Spazz and Infest. He, too, sees Koichi as a truly unique figure—one deeply appreciated by the many heshers in the international beer circuit.

“[Koichi] really is a pioneer,” Dodge told me over the phone. As Dodge sees it, the crossover between the craft beer and heavy music scenes is natural. “[Thrash Zone] shows me that there are people like me who are excited about both extreme music and good beer. [Koichi] is just super down-to-earth and cool, and he just really appreciates connecting with people who have that similar mindset—very DIY, very grassroots.”

While his bar remains tucked away and unpretentious, there’s no question that Koichi’s influence has resonated through Japan’s craft beer world. After Thrash Zone opened in 2006 and began importing and then producing ultra-hoppy ales and West Coast beers, Koichi became the go-to guy for other slowly burgeoning craft beer bars looking to follow suit. And a USDA report from last year shows that while overall beer consumption in Japan has been on the decline, craft beer’s market share has quadrupled.

“Andrew Balmuth would always bring [beer] people there, and from there, the popularity just spread. I definitely think he was influential to the early craft beer bars, and he emboldened others to feel like they could do that,” Beville said. “They saw [Thrash Zone] and thought, I’ve got a chance.”

Koichi is happy just holding it down at his tiny bar. Balmuth said that he’s dropped in a couple of times while Thrash Zone was empty to find him practicing his guitar, playing lightning-fast licks to no one.

“In a way, it’s his church. It’s his house,” Balmuth said of the Thrash Zone experience, “And he’s kept it that way.”

This article originally appeared on VICE US.