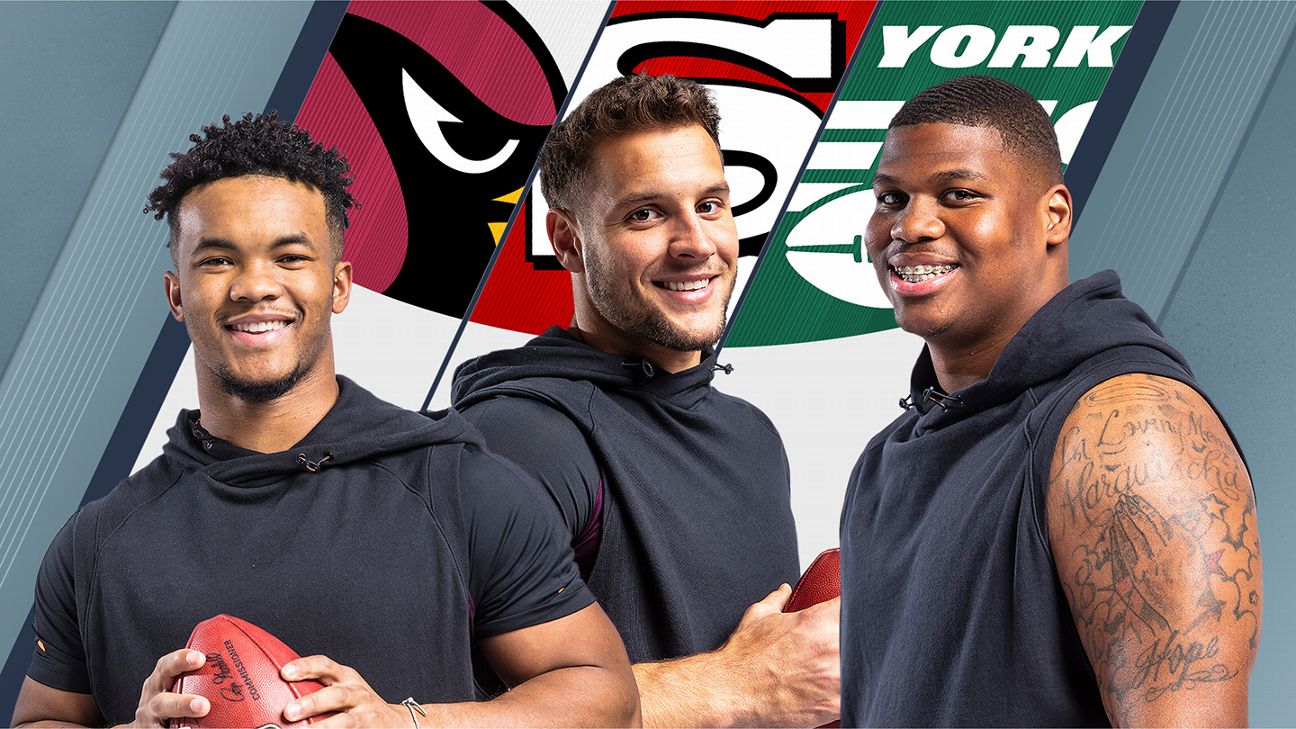

Can Kyler Murray continue legendary winning ways with Cardinals?

TEMPE, Ariz. — Kyler Murray‘s high school résumé is a thing of football lore in Texas.

Forty-two wins. No losses. Three straight state championships. Three championship game MVPs. Gatorade Player of the Year.

“It’s unbelievable,” said Tom Westerberg, Murray’s coach at Allen High School. “We played at the highest classification in the state of Texas, and to know that we ran the table three times with him, it’s unbelievable.”

Unbelievable? Yes. Incredible? Yes. New? No.

Murray, the quarterback taken No. 1 overall in the NFL draft last month by the Arizona Cardinals, didn’t start winning when he transferred to Allen before his sophomore year. By then, he’d been doing it for years. All he has ever done is win, and he has done it at every level. Now he joins a Cardinals team that finished 3-13 last season and has reached the playoffs just four times this millennium.

Kyle Nelson was on the board of the Lewisville Football Association in 2002 when a friend told him he had to watch one of the flag football players in the 5-6 age group. Nelson, understandably, wasn’t interested.

Then he watched Murray — as a 5-year-old — score five touchdowns in the first half.

“I was like, ‘Wow, this kid is pretty special,'” said Nelson, now the league president. “I just remember watching him just pretty much dominate that game as a 5-year-old.”

Catch up on the draft:

• Pick-by-pick analysis »

• Kiper’s grades » | McShay’s best picks »

• Team-by-team analysis » | Takeaways »

Catch up on free agency:

• Biggest impact moves for all 32 teams »

• Winners and losers of free agency »

• Barnwell: Grades » | Lessons from FA »

More on the draft » | More on FA »

Murray dominated the Lewisville Football Association for the next seven years, losing just one game, as Nelson recalls, and winning six league titles out of a possible seven. And Murray did it often by playing against older players. Because of his August birthday, Murray was always among the youngest kids in his age group.

Nelson saw firsthand how tough it was to beat Murray: He coached the team that gave Murray what’s believed to be his lone youth football loss, in 2006, when Murray was 9.

“It was a pretty big deal when that happened,” Nelson said. “I’ve been doing this 19, 20 years now. He’s the best youth football player I’ve seen. Hands down.”

By the time Murray finally took the field at Huffines Middle School, his reputation preceded him. Dick Olin, then the head coach at Lewisville, installed a watered-down version of the varsity’s scheme, which was essentially the Air Raid, for Murray to run.

It didn’t take long for Murray to pick up the offense, said Heath Naragon, his eighth-grade coach at Huffines, so he’d go back to Olin and get another part of the playbook to install. Murray would absorb it and Naragon would go back to Olin. It got to the point where Murray’s eighth-grade team was running an offense more complex than the junior varsity but not quite as complicated as the varsity.

“He was very knowledgeable,” Naragon said. “I’ve been doing this, I don’t know, 11 years now and I’ve never seen anybody like that.”

It translated into sheer dominance on the field. Huffines lost once that season, in the semifinals of the middle school playoffs — because Murray missed the game with a shoulder injury.

What stood out to Naragon beyond Murray’s arm strength, which he believed was better than 99 percent of Texas high school quarterbacks as a seventh-grader, was Murray’s poise.

“He doesn’t get rattled,” Naragon said. “Nothing really affects him.”

And as good as Murray was in eighth grade, he was better in ninth. He began showing an advanced understanding of Olin’s pass-happy scheme after having been in it for a year, and as a ninth-grader he started taking ownership of it.

Sonny Dack, the varsity running-backs coach, helped Olin and Naragon coach the freshman team. He saw Murray begin holding his teammates accountable, whether it was the offensive line, the running backs or the wide receivers. He’d let the receivers know if their routes weren’t crisp enough or work to figure out why they dropped a pass. Murray had an encouraging nature when getting on his teammates. He began running parts of the offense at the line of scrimmage. He’d audible in and out of plays.

“He knew what everybody was supposed to be doing and he expected him to do it perfect,” Dack said. “He delivered and then some once he got to the ninth grade.”

No one could figure out a way to stop him, Olin said. And Murray’s height never mattered.

“Everybody told me, you’re too small,” said Murray, who today is listed at 5-foot-10. “You just learn to deal with it.”

Olin, who remains close with Murray — he eventually drove him to a visit at Texas Tech, where Kliff Kingsbury was coaching — was fired after the 2011-12 school year. Murray transferred to Allen High School, where the rest, as they say, is history. Quite literally.

By the end of high school, Murray firmly established himself as the front-runner to be named the best high school quarterback Texas has ever seen.

Murray dominated his competition, throwing for 10,386 yards and 117 touchdowns while running for 4,129 yards and 69 touchdowns. His senior year showing of 4,713 yards and 54 touchdowns earned him the prestigious five-star rating by every major recruiting service.

“I had never seen anybody like him,” Olin said. “Kyler was the best I’d ever been around and I was around some really good ones.”

When he finally got his chance in college, he picked up right where he had left off. Murray went 12-2 in 2018, his only season starting at Oklahoma, and won the Heisman Trophy after passing for 4,361 yards with 42 touchdowns and seven interceptions. He also rushed for 1,001 yards and 12 more TDs.

Murray enters the NFL with plenty of accolades but a difficult test ahead. Arizona hasn’t gone to the playoffs since 2015, which was also the last time it had a winning record. Murray will be charged with resurrecting an offense that was one of the worst in the league last season.

Murray’s legend as a high school player is known by some in his new organization. Fellow rookie wide receiver Hakeem Butler, who went to high school in Houston, had heard about the kid who accounted for something like 25 touchdowns in his first four games.

“I was like, ‘Nah, this kid ain’t human,'” Butler said.

Even Kingsbury, who starred at New Braunfels High School outside San Antonio and is a member of the Texas High School Football Hall of Fame, couldn’t explain what it was like to be a high school star of Murray’s caliber in Texas.

“I can’t. I’ve never seen one — that big of a star,” Kingsbury said. “He was the best player arguably to ever come through the state. When you talk about [42-0] and all the records he broke and things of that nature, I have no idea what it feels like.”