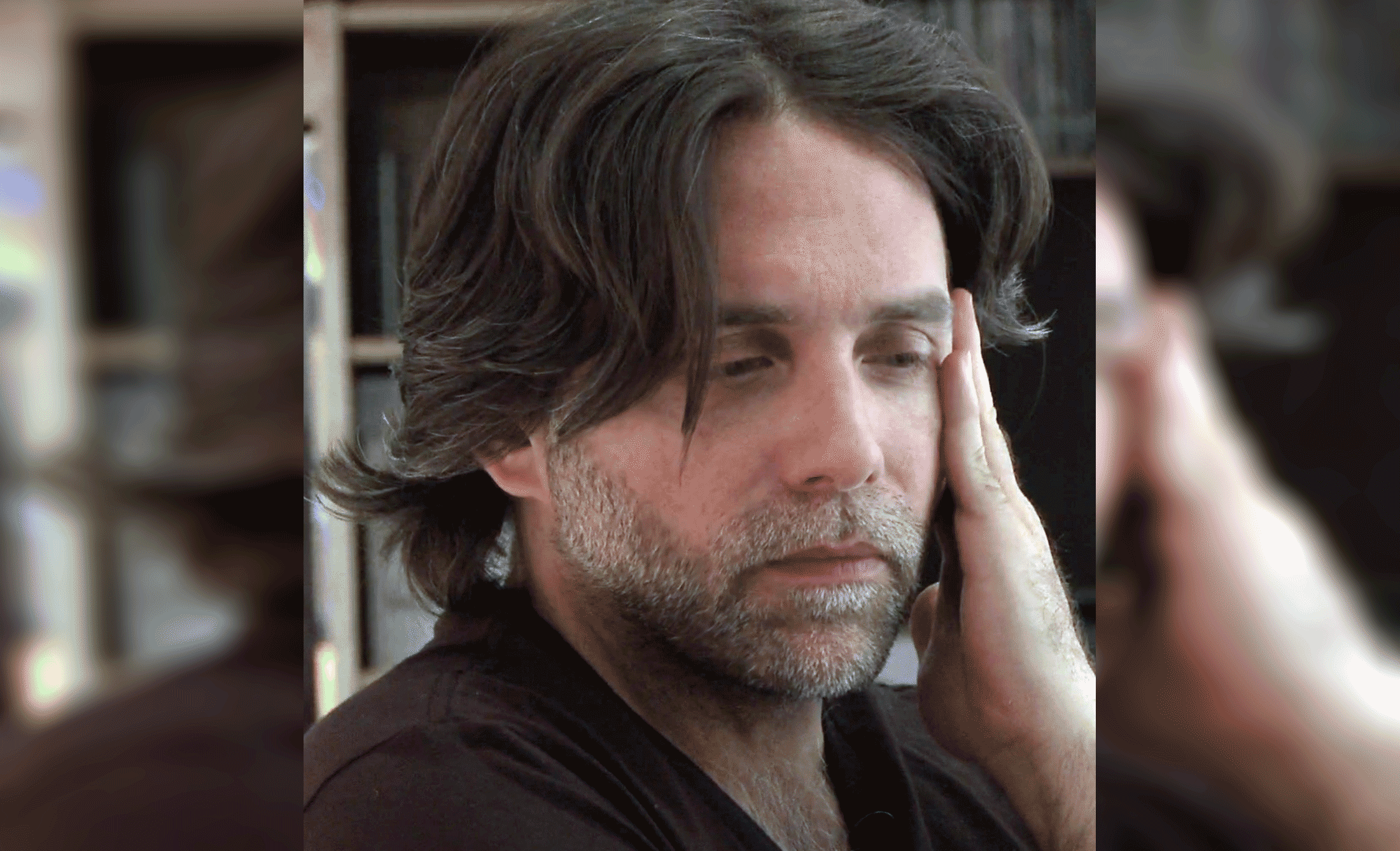

An Ex-Prosecutor Breaks Down the ‘Sex Cult’ Trafficking Case Against NXIVM Leader Keith Raniere

Credit to Author: Sarah Berman| Date: Wed, 15 May 2019 16:13:25 +0000

The racketeering and sex trafficking trial against self-help guru Keith Raniere has barely entered its second week, and already a number of disturbing details have been unearthed.

The court has heard the infamous founder of NXIVM believed the government was spying on him because of his high IQ, that some followers thought Raniere’s energy could affect the weather and computers, and that students were told Bill Clinton was supposedly part of a conspiracy to destroy Raniere’s first multi-level marketing business, Consumers’ Buyline. All of that came on top of the harrowing testimony from one of Raniere’s former “slaves,” who called him “Grandmaster,” and said she felt she had to go along with his sexual advances or risk having her family relationships destroyed.

But despite the high-profile names, strange “cult”-style practices, and bottomless bank accounts associated with NXIVM, the broad strokes of the trial are not all that different from cases against street-level pimps, according to former federal prosecutor Krishna Patel, who specialized in sex trafficking cases first in the Southern District of New York and later in Connecticut. The nuts and bolts of making these cases—proving a level of fraud, force, or coercion that made victims unable to say no—remain the same, she said.

Patel, who served in the Department of Justice from 1999 to 2015 and now works for the anti-trafficking advocacy organization Grace Farms Foundation, told VICE that the first few days of the trial have followed a pattern she has personally used to convict sex traffickers. It’s a strategy in which victims paint a picture of a subculture used to enforce control, and juries learn about their close attachment to the defendant.

While several NXIVM members, including actress Allison Mack, have pleaded guilty to various charges, none have copped to “sex trafficking” charges even as they have largely backed prosecutors’ accounts of a twisted web of blackmail material (including nude photos), orders to have sex with Raniere, and even forced detention and threats of deportation. Trafficking, of course, is a contested crime and political issue that sex worker advocates say is used to justify crackdowns on vulnerable people who are just doing their jobs. In New York, where efforts to decriminalize sex work have made inroads with state politicians, advocacy organizations have good reason to resist overboard definitions that lump all sex work in with trafficking. But criticisms of that kind of overly broad brush have not factored heavily into the case, and the allegation is one of the most serious facing Raniere, who has pleaded not guilty on all counts. A conviction could land him in prison for the rest of his life.

Patel recalled beginning her focus on sex crimes, most of them involving girls under 18, back in 2005. One of her first cases involved a girl as young as 12, and expanded to include 10 victims of the same pimp. From there she worked her way up to deputy chief of national security and major crimes unit for the US Attorney’s Office in the District of Connecticut. She said that while most traffickers end up pleading before trial, the cases that go before a jury usually follow a familiar script.

In the trial against Raniere, the first witness on the stand was 32-year-old “Sylvie,” a woman who first came to Albany, New York, from the UK when she was 18 years old, and said she later became a “slave” in a secret society called “DOS” within NXIVM that claimed to be about women’s empowerment. Starting with a traumatic personal account—rather than some kind of technical appraisal of a group prosecutors have suggested operated like the mob—was wise, Patel argued.

“It’s a very nice trial strategy by the prosecution to start with a very human story, instead of making it about the organization,” Patel said. “You want to have her testify that these were things she didn’t want, that she didn’t feel like there was any way she could say no.”

In the case of NXIVM, which includes allegations of confinement, branding, and the threat of damaging information and photos being released, Patel saw strong evidence of force, fraud, or coercion. The “collateral” women handed over in order to hear about the “special project” known as DOS remained a threat throughout their membership in the group, even if it was never released. “That’s the gun to her head,” Patel said.

Similarly, Patel said, in some of her own cases, threats of violence were not necessarily acted on, but created a situation where the victim had little choice but to assume the danger was real. “Each of us is different—we all have a different point where we would say, ‘I’m going to go along with this because I’m afraid.’ The question is, does the jury believe her, and if they believe her, then you’ve got a trafficking case.”

Patel noted that shame is usually a good indicator a person didn’t want to be there—feelings Sylvie expressed on the stand last week. “I remember the thing that kind of sparked anger in me more than anything was the use of the word ‘special,’ actually, and that he was calling me ‘brave,’ because I felt so disgusting and ashamed,” she testified. “I just thought—I felt like it was all lies, like it just felt disgusting, and it wasn’t true.”

Sylvie testified under cross-examination that she sent a nude photo to Raniere every day, often with the recurring message “good morning, grandmaster” and heart emojis. While this could be interpreted as a bit of roleplay between consenting parties, Patel said, prosecutors could also use it to establish the language and subculture of a trafficking operation.

In more typical cases Patel has prosecuted, this language usually establishes some kind of rank among victims. A “stable” of trafficked women will often call each other “wife-in-laws,” and will answer to a “main girl” who has status above the others, she explained. In the case of NXIVM, titles like “master,” “grandmaster,” and “slave,” may serve to establish their own hierarchy.

Sylvie was also cross-examined about whether or not she felt love toward Raniere. “That’s trying to say, ‘Listen, this was somebody who chose to do this on their own,’ without saying those words,” Patel said of the defense strategy.

It’s not uncommon in a trafficking case, even one involving violence and threats, for victims to resist any help from authorities, Patel continued. “They will kick and stomp and spit and yell at law enforcement,” she said. “[The defendant] is usually this person’s father, boyfriend, or the only person who truly loves this person. That bond is so powerful, and you are the person breaking this bond.”

Patel expected the branding and initiation reportedly at the center of NXIVM’s secret sorority will also become a key part of the prosecution’s case against Raniere. In her experience, “Gorilla” pimps, as she called them, often stage some kind of initiation for new recruits, which could be anything from a public humiliation to a gang rape. Branding itself is common across many trafficking cases, she continued, working to “break down any of our normal psychological defenses.”

Finally, Patel said, it’s not uncommon to have a manipulative and charismatic personality at the center of a case like this. Prosecutors will sometimes choose to bring in a forensic psychologist to explain how a particular kind of manipulator, who claimed to be able to fulfill targets’ dreams and exploited their vulnerabilities, could establish control over seemingly powerful or high-status women. In that way, cult leaders may not be so different from pimps.

Of course, sex trafficking is only one part of the government’s case against Raniere. As part of racketeering charges, prosecutors were also expected to bring evidence of extortion, forced labor, sexual exploitation of a child, and possession of child porn—though separate child porn charges were recently thrown out on a technicality. Once the six-week trial is concluded, Raniere may face a second trial for those alleged offenses.

“The crime’s already proven because they have the images,” Patel said of that possibility. “Now they’ll get a whole second shot at this guy.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Folllow Sarah Berman on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.