FCC Commissioners Say the Agency Won’t Tell Them About Phone Location Data Investigation

Credit to Author: Joseph Cox| Date: Mon, 13 May 2019 17:29:33 +0000

Two Commissioners of the Federal Communications Commission say that the agency has not been forthcoming about its investigation into the sale of consumers’ real-time cell phone location data by AT&T, Sprint, Verizon, and T-Mobile. The commissioners told Motherboard that they don’t have insight into what’s actually being investigated. It appears the investigation has not been prioritized by the agency.

After The New York Times and Senator Ron Wyden found telecommunications companies were allowing their customers location data to be accessed by low level law enforcement without a warrant, the FCC said it launched an investigation into the practice. Then, when Motherboard revealed that some of the telecom companies had been selling access to that same data to a slew of middlemen brokers, eventually ending up in the hands of bounty hunters, the FCC reiterated it was investigating the sale of location information. Since then, Motherboard has also found that the problem was much larger than previously understood, and showed that hundreds of bounty hunters and bail bondsmen could track most phones in the United States.

But Jessica Rosenworcel and Geoffrey Starks, two of the five FCC commissioners who lead the agency, want more information. Around a year after the inquiry was opened, there have been no public updates, and the two commissioners said they have little knowledge on what’s actually being investigated.

“So far it appears that the FCC is more interested in protecting the privacy of its investigation than the privacy of wireless consumers across the country,” Rosenworcel told Motherboard in a statement.

Do you know anything else about the sale of location data? You can contact Joseph Cox securely on Signal on +44 20 8133 5190, Wickr on josephcox, OTR chat on jfcox@jabber.ccc.de, or email joseph.cox@vice.com.

“In my enforcement experience, cases with clear and significant public safety implications must be prioritized and resolved expeditiously. The stakes here couldn’t be higher,” Starks said in an emailed statement.

“The alleged misconduct touches all the major wireless carriers, hundreds of millions of their customers, and many other third parties. The data at issue is among our most sensitive—our real-time location,” he added.

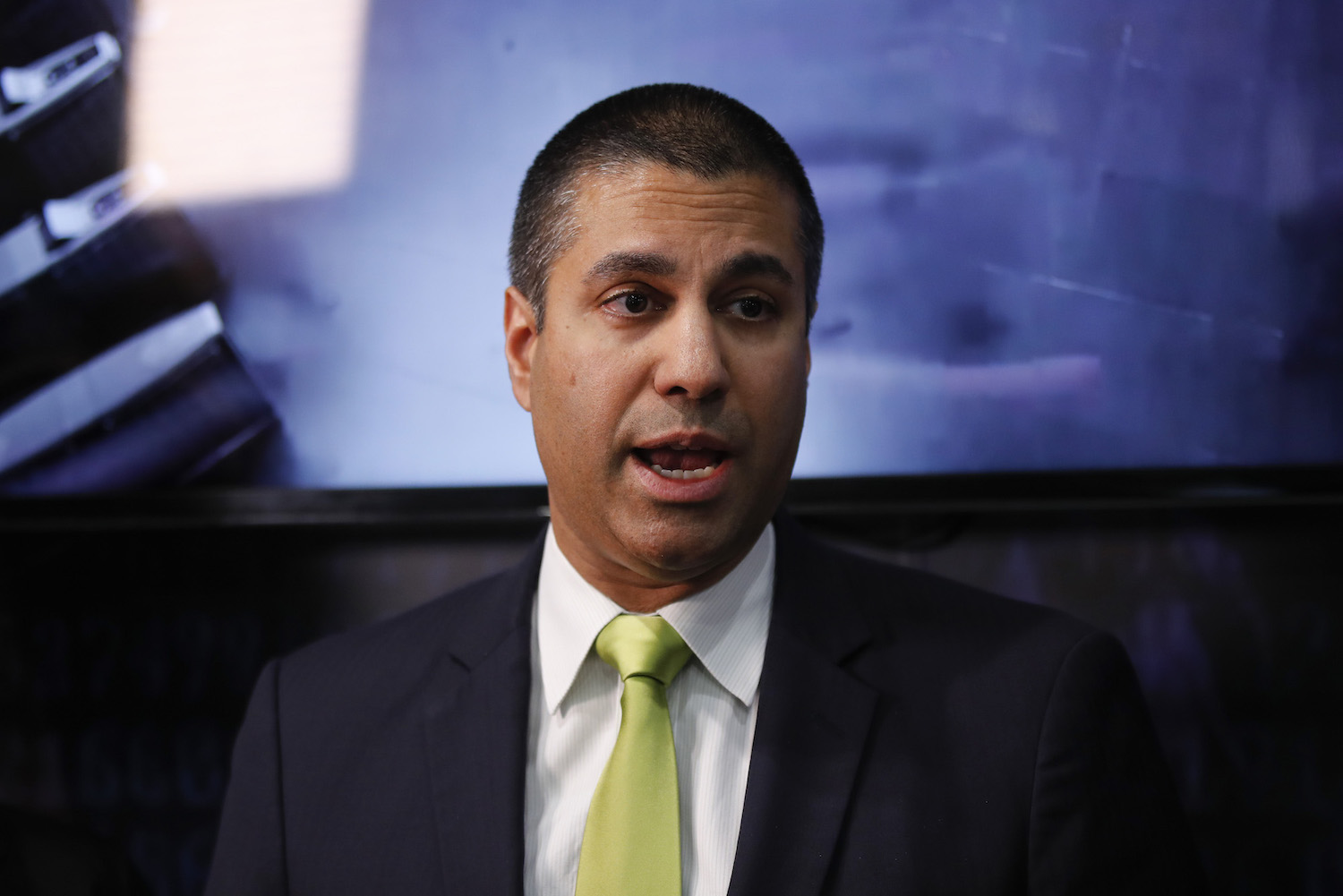

Under FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, the agency has been openly divided. Rosenworcel and former Democractic commissioner Mignon Clyburn publicly fought to keep net neutrality intact as Pai repealed it; Clyburn even publicly protested the decision in front of the FCC’s headquarters.

The FCC has the power to launch investigations and to subpoena companies in order to acquire internal documents or compel testimony from employees. The FCC also sends Letters of Inquiry (LOI) and has the power to physically inspect facilities. In this case, the FCC’s mandate would be over the wireless carriers themselves, and not the so-called location aggregators they sold data to, such as LocationSmart and Zumigo.

Like other law enforcement agencies, the FCC does not comment on active investigations; an FCC spokesperson reiterated that point in an email on Thursday.

But a source familiar with the FCC investigatory process said that this particular investigation could have moved quicker. The FCC Chairman’s office, when it wants, can act faster, they said. Motherboard granted the source anonymity to speak more candidly about FCC processes.

The FCC may also be running out of time to investigate. The statute of limitations on issues the FCC investigates is generally one year after the violation occurred. Although investigators or administrations may disagree on when exactly a violation happened—was it when the problem came to light in media reports or when a specific phone was located, the source said—the one year anniversary of the first New York Times article on the issue was last week.

“It has been a year since these practices first came to light, which means that we are running up against our one-year statute of limitations,” Starks added. “The Commission has done nothing to assure consumers in this period of time that they are safe and their data is protected. At this point, we should all know more about what the Commission is doing to protect our sensitive data.”

The FCC can extend the time period with agreement from the subject of the investigation, with a so-called “tolling agreement.” The FCC did not respond when asked if it had obtained such an extension.

“This is a matter of personal and national security.”

After Motherboard’s initial investigation showed AT&T, T-Mobile, and Sprint customer real-time location data was ending up in the hands of bounty hunters, 15 Senators called for the FCC and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate. Frank Pallone, the Chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce also asked Pai for an emergency briefing on the issue. Pai refused, with his staff telling Pallone that the issue is not a threat to the safety of human life or property that the FCC would address at the time. Pallone made the request during January’s government shutdown, but as Pallone said in a previous statement “There’s nothing in the law that should stop the Chairman personally from meeting about this serious threat that could allow criminals to track the location of police officers on patrol, victims of domestic abuse, or foreign adversaries to track military personnel on American soil.”

On Tuesday, in response to a question from Senator Chris Coons during the FCC and FTC Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Request hearing, Pai said the investigation was covering “any and all carriers that might be exchanging in the practice,” but didn’t provide any more specifics, including whether the investigation was tackling the bounty hunter issue or when it would be completed.

Commissioner Rosenworcel added, “This is a matter of personal and national security. The silence of the agency on this issue is simply unacceptable.”

Subscribe to our new cybersecurity podcast, CYBER.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.