How an Augmented Reality Game Escalated into Real-World Spy Warfare

Credit to Author: Elizabeth Ballou| Date: Wed, 08 May 2019 16:30:51 +0000

At 4:30 PM on February 17th, 2017, Meng was getting ready to take the last ferry to the island at the center of Qinhu National Wetland Park in Jiangsu Province, China. In one hand was a bag of camping equipment and a telescope. In the other, a phone, which she checked obsessively. Meng had spent the day traveling from her home in Beijing to Shanghai and then Nanjing, assembling a trusted squad of eight people that she rarely met in-person. They told park officials that they were there to do some overnight birdwatching with their telescopes, but that was a lie. The telescopes were just for show. Meng and the others were there to execute the final step in an international conspiracy to open a secret line of communication to another Resistance position in Alaska.

Meng was tired. The weekend before, she’d flown from Beijing to Seattle and back in less than forty-eight hours in order to meet one of her counterparts and obtain the key required to complete the connection from Jiangsu Province to Alaska. Then she’d spent the following days coordinating with the Nanjing group. Now she was getting ready to sleep in a tent on a backwater island. She only hoped that all her effort to marshal other teams into following her lead would pay off, because her plan hinged on whether they could take and hold that island long enough to complete their mission.

At first, Meng hadn’t wanted to get involved in the Resistance. But she made an ideal agent, which is why they recruited her. She traveled a lot for work, and made enough money that she could travel extensively outside of it. Those two factors would make her a powerful player within the intensely competitive community around Ingress, an augmented reality mobile game. It uses the same geolocation functions as an app like Foursquare, but places them in the context of a sci-fi story about factional intrigue: to seize territory, players go to different physical locations in the world. Which is where Meng came in. In 2016, some friends convinced her to start doing them small favors on her travels, little side-trips that wouldn’t take her too far out of her way. Within a year, 25-year-old Meng was planning and executing some of the group’s most ambitious operations while working another job full-time. She went about it with the zeal of a fanatic and the secrecy of a clandestine operative. Then, just as suddenly, she stopped.

Ingress is not an easy game to understand or play. Unlike Niantic’s later hit Pokémon Go, which has a cheerful, casual tone, Ingress is a sci-fi tale about humanity on the brink of destruction. The discovery of a powerful force called Exotic Matter (XM) divides players – called agents – into the Resistance and the Enlightened. According to the game’s fiction, the Resistance believes that XM is dangerous and wants to quarantine it, while the Enlightened want to harness it. It’s not a very original story, but it doesn’t need to be. The hints of plot are only there to propel players into conflict, and that creates the real story.

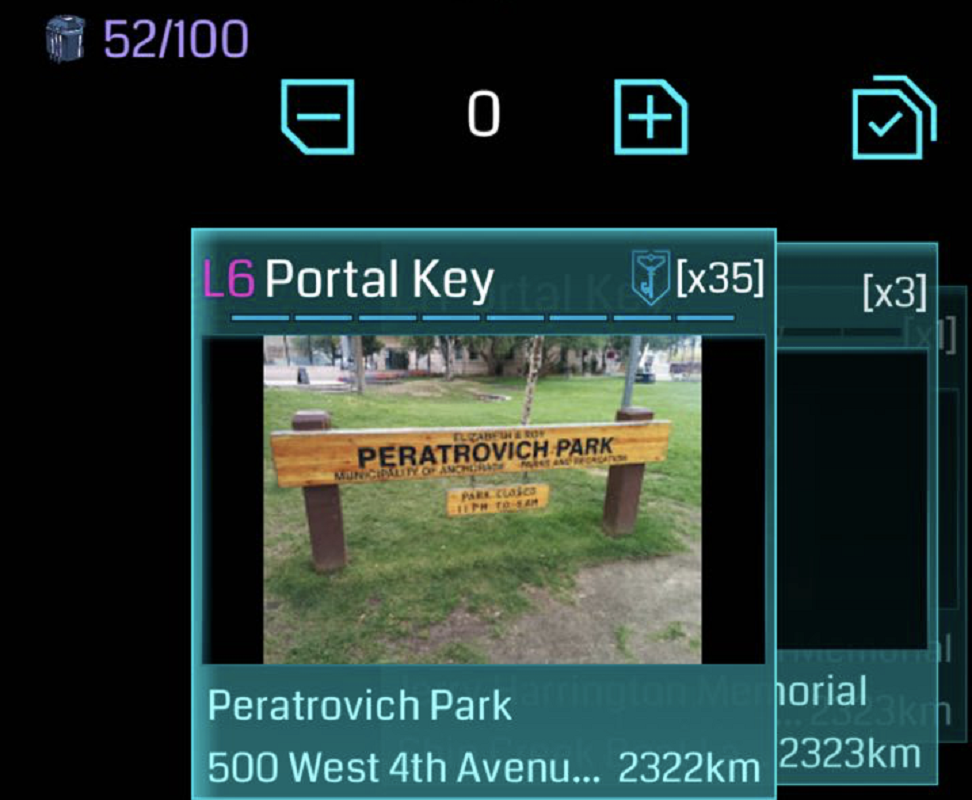

Ingress players take part in the war by traveling to “portals,” special locations in the real world which they can hack through the mobile app. The app displays a map of the player’s surroundings in moody black and white, with Resistance territory marked in blue and Enlightened in green. When a player hacks a portal, they receive items, like weapons and shields; resonators, which are used to capture a neutral portal; and portal keys, which serve as unique portal IDs. Placing eight resonators on a neutral portal means that the portal belongs to the player’s faction. By standing close to a portal their team controls, players create links to other portals whose portal keys they possess. The more links a faction controls, the more powerful they become.

Meng first heard about Ingress in 2012, when she was a Chinese college student living in St. Louis, Missouri. Meng doesn’t consider herself a gamer, but the beta version was getting a lot of buzz because it required players to go outside, so she gave it a try. Today, map-based AR games are common, but in 2012, Ingress was the only game of its kind.

Right away, Meng was disappointed. Her campus had no portals, or bases, so she couldn’t play. “I deleted the game about half an hour later,” she told me. Meng didn’t think about Ingress for the next four years.

By 2016, Meng had moved back to Beijing and started a busy career, first in tech journalism and then in investment. One night, some friends asked if she remembered Ingress. “You live very close to portal clusters,” Meng recalled one saying. At their urging, she redownloaded Ingress and saw that the world was much more accessible. “There was a park where I lived, and the park alone had thirty portals,” Meng said. This time, she stuck with the game.

Choosing the right portals to link, and when to link them, is key to playing Ingress well. Dedicated players hang out on forums and messaging apps to talk strategy, just like any other gamers. The difference: Ingress players constantly meet up in real life. Fortifying a portal to top strength means putting only the highest level resonators on it, but a player can only place a single high-level resonator on a particular portal. That means eight top-tier Ingress players have to assemble within a few meters of the portal they’re trying to take. Coordination is everything.

Some compare Ingress to a global game of capture the flag, but Mitu Khandaker, an AR/VR expert and game design professor at NYU, thinks it’s more like a hyper-engaged geocaching league. Geocaching is a global, multiplayer game that was born in 2000, when GPS technology became good enough for people to pinpoint specific locations with their GPS receivers. An American named Dave Ulmer hid a stash of items—books, a slingshot, a can of beans—in the woods outside Portland, Oregon, posted the GPS coordinates on an online message board, and dared people to find the stash. The game caught on fast, and people all over the world created their own geocaches.

According to Khandaker, the allure of map-based AR games like Ingress and Pokémon Go is similar to the thrill that geocachers felt when they left their computers and hiked into the middle of nowhere with people they hardly knew. “It’s about, ‘Are you willing to go out into the world and construct these shared, playful experiences with strangers?’” she said.

Zhao Leon, a veteran Ingress player who befriended Meng, agreed. “Everyone can play Ingress by themselves, but you cannot enjoy the game without a community. The community connects people and makes you happy. The community makes you care, not the game itself.”

But Ingress doesn’t always feel playful or happy. The friends who convinced Meng to re-download Ingress thought of the game as a series of battles, and Meng came to view it that way, too. “The main objective of the more devoted players is about commanding wars. Ingress is a war game,” she said. In addition to the official Ingress app, agents use a host of fan-made apps and websites that let them strategize by mapping links and digging up personal information about the enemy. Top players spend months planning for Anomalies, special events that Niantic announces several times a year. Those top players then reach out to dedicated agents in the target countries, who then reach out to players they know in target cities, until the faction finds someone who can access any given portal in the world. “We can think of it as, there’s a council at the top looking at global stuff. They have regional contacts and leaders representing different continents, and then down to different countries and different cities,” Meng told me. She paused. “I’m out of the game for two years now, otherwise I wouldn’t be saying this to you.”

I wanted to see what Meng saw, so I downloaded Ingress and joined the Resistance. I spent the next month hacking portals along the New York City subway lines, feeling proud whenever I managed to create tiny links. One evening, I took the subway in the wrong direction and ended up in Queens. As I waited for a train to take me back to Manhattan, I pulled out my phone and captured several low-level Enlightened portals within my reach. After a few seconds, my phone erupted with notifications. An Enlightened player was destroying all the Resonators I had just deployed. I spun around, looking for the person who was doing it, but the platform was almost empty. Then I saw a lone figure across the tracks, looking straight at me. Our eyes met. He seemed angry.

The tracks began to rumble, and then a train screeched to a stop between us. I hurried on, eager to get away. In that moment, Ingress felt as real to me as the train floor beneath my feet.

By the end of 2016, Meng also felt like Ingress was real. At first, she played solo because she felt likeIngress groups she’d checked out on QQ, a Chinese social media app, had too much drama. “I saw people chatting and thought that they were really stupid,” she said. Then other players, who knew she traveled a lot for work, began asking her to pick up portal keys in other cities.

One of these players was Li Ratoo, a Resistance agent from a town outside of Shanghai. Ratoo had been playing Ingress for two years and had worked his way up the informal hierarchy of China’s Resistance community. At the end of 2016, Ratoo and Meng met in person at an Ingress event in Nanjing. He remembers being impressed by Meng’s dedication. “She showed a very strong sense of leadership,” Ratoo said. “When you show leadership, people will recognize you very fast.” Meng also met some of the other most active Ingress players in China, including Leon, who has updated his Ingress blog on WeChat at least once a day for the past three years; and Huang Nuo, one of Beijing’s top community organizers.

Soon, Ingress had become such a major part of Meng’s life that she had started spending her weekends traveling to events in nearby cities. She also began to make battle plans alongside the others. Ingress players in China don’t have formal community positions; instead, “influence comes from how much time and effort you put into the community,” according to Nuo. “If it’s more, then people listen to you.”

And people were starting to listen to Meng. “One of the plans I drew up required a hundred people to show up in a specific spot in Taipei at 5:00 in the morning. And they did [show up],” she said. Meng didn’t even know most of the agents until that morning, when a hundred sleepy-eyed players helped her create portals in a specific pattern for an operation. The event, Meng said, was “super complicated. You had to have 100 people there, doing specific actions at the same time that were choreographed before.”

The Enlightened showed up and began destroying portals before she and her team could finish the pattern, but that didn’t really bother Meng. For her, Ingress wasn’t about the Resistance defeating the Enlightened. She still thought faction drama was childish. “I think the fun was drawing out the plan,” Meng said. She loved getting total strangers to work together, executing plans that she had drawn up after hours and hours of painstaking coordination. “I had a printed-out playbook of specific actions for each group that they had to access,” Meng told me of the Anomaly in Taipei. Her voice grew dreamy as she recalled the details, like a football coach reliving their team’s best plays.

But there were parts about Meng’s new passion that grated on her. One was the frustration caused by bad sportsmanship. Some players were spoofers, or cheaters who faked their GPS location to fool theIngress app into thinking they were in a specific place. To Meng, Ratoo, Nuo, and Leon, spoofers ruined the plans they worked so hard to make. “It’s a huge problem for the whole game,” Nuo told me. “There are principles. Without rules, there is no victory. I believe that cheating is totally unacceptable, but some people don’t think that.”

Other players held grudges, spread vicious rumors, and even stalked agents from the other factions. Ratoo told me that Enlightened players started accusing him of photographing them with a long-range camera as an intimidation tactic. Meng said that if agents wanted to insult a specific player from the other faction, they’d track that player’s movements, figure out where they lived, and take down their “couch portal,” or the portal closest to their apartment. Targeted agents felt like their privacy had been violated.

Meng rarely told her non- Ingress friends what she was doing, even as she spent up to six hours a day playing, planning, and traveling. “Because of the operation security, it was very hard to talk about these things, even with close friends,” she said. In addition, no one knew her as a dedicated gamer, and she didn’t want them to think she was strange for devoting so much energy to a game she hadn’t even liked until less than a year ago. Sometimes she felt like she was living a double life: office worker by day, Resistance operative at night and on the weekends.

None of these problems seriously dissuaded her. Still, the next event that Meng had to plan for would challenge her in ways she hadn’t expected.

At the beginning of 2017, whispers began to circulate about an Anomaly that Niantic, the developer behind Ingress, planned to hold in February.

The Anomaly would be a Global Shards event, a complicated and labor-intensive operation. Story-wise, the shards were fragments of images that depicted thirteen characters from Ingress lore. Shards would appear in portals all over the globe, and they would move every five hours. The two teams had to capture shards, then move them to designated end portals for points. Whoever had the most points at the end of the event would win, and the fates of the thirteen characters would change depending on which team controlled more of the shards.

Ratoo was nervous when he heard about the upcoming Anomaly. “People were not happy about it,” he said. “It’s very exhausting for agents to get involved. You need to explain why they should be out at two or three in the morning on a work day.” He’d participated in previous shard Anomalies and remembered the burnout. Normally, executing operations in Ingress required months of planning. During Global Shards, players only had hours. Despite Ratoo’s reservations, he, Meng, and the others were ready. They would do whatever it took to make sure the Resistance had the manpower it needed.

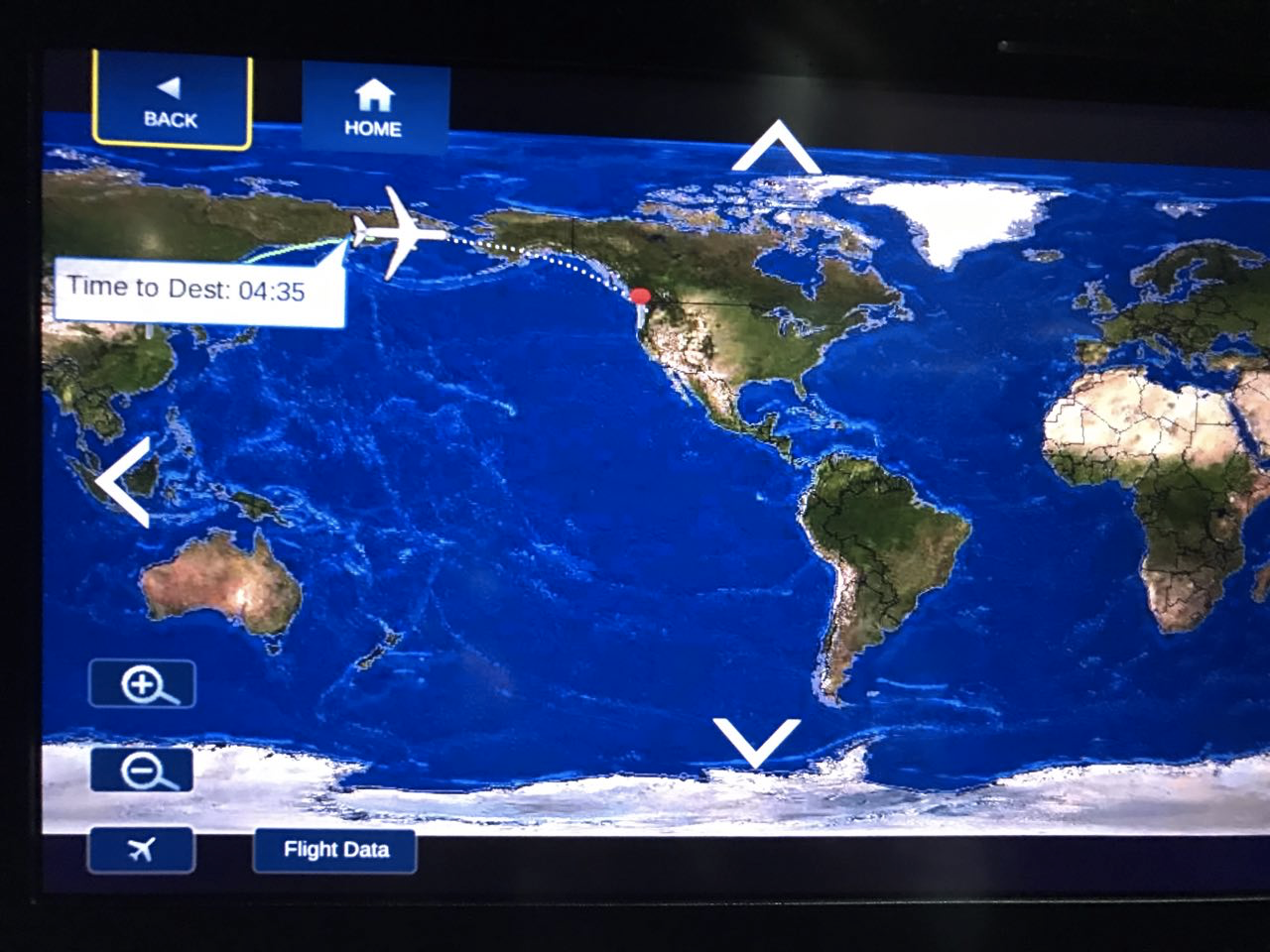

The first round of shards spawned on February 10th, 2017. All over the world, Ingress players scrambled to chart the most efficient links between those original portals and the portals where the shards were supposed to end up. One of the target portals was in Anchorage, Alaska, and Meng and the others realized that it was the best match for a shard that had spawned nearby in Hangzhou, China.

Right away, they knew they had a difficult task ahead. One, they didn’t have a key to the target portal in Anchorage (to build a link from Portal A to Portal B, an agent must have a key for Portal B). Two, even if they did get a portal key, they would have to construct a link over 4,400 miles long. Links can’t be built through territory controlled by the rival faction, so the Resistance had to make sure that nothing, not even a single Enlightened link, stood between Hangzhou and Anchorage.

The team got to work pinging Resistance players all over Russia, the United States, and Southeast Asia. It didn’t take long for them to find an agent in Anchorage who said she would fly to Seattle if someone could meet her there – but that still meant a Chinese agent had to fly to Seattle. “We looked around us and knew we didn’t have a lot of choice and it was going to be hard,” said Ratoo.

Then Meng stepped up, and bought a ticket for the next flight to Seattle; an 11-hour trip that departed the same day. “I still remember the flight number: DL128. It made that kind of impression. It was a very tremendous thing for the community and for us,” Ratoo told me. In Seattle, she met with the Alaskan Resistance agent, got the portal key, and came straight back to Beijing.

While Meng was in the air, Ratoo, Nuo, and Leon were busy drawing up plans. They tried to clear the way for the link to Anchorage, but Enlightened agents blocked them at every turn. By the time Meng landed, they still hadn’t figured out how to make the link. Finally, they settled on a location they thought the Enlightened would never figure out: a portal in Qinhu National Wetland Park, an isolated nature preserve on the coast. Eight agents, plus one for backup, would travel to Jiangsu Province and make the link at night. They’d camp out, waiting until the shard jumped, then head home in the morning.

Once again, Meng took charge. She and Ratoo would go to Jiangsu themselves, buy camping supplies, and pick up a crew of Resistance agents in Nanjing. That was how Meng found herself on board the ferry to the island at the center of Qinhu National Wetland Park, holding a telescope so that the park employees would believe that they were really there to birdwatch. Everything she’d done for the sake of Ingress had been exhausting, but they were finally going to make the link, she figured. No one else would be on the island, so the nine agents would be left alone to concentrate on the game.

It didn’t take them long to discover that they weren’t alone at all.

XM is the substance that drives the story behind Ingress, and it’s present all over the in-game map. Players suck up ambient XM just by walking around, and they use the energy it provides to attack portals or make links. Portals have a perfect circle of white XM particles around them, which is only disturbed if a player starts absorbing it.

When Meng and her crew reached the island, they found a deserted building where they set up their tents. Then they walked the perimeter of the island, checking to make sure everything was safe. That was when Ratoo noticed that the circle of XM around the portal was broken. All of the Resistance agents had a full supply of XM, which meant someone else was absorbing the substance.

“I was like, ‘uh oh,’” said Ratoo. “Another agent said, ‘There are Enlightened agents here.’” The sun had gone down, so the nine of them peered into the darkness, trying to make out human shapes. Though they couldn’t see anything, their phones began to buzz, the same way mine had on the subway platform. “We were ambushed,” Ratoo said.

The portal, which they had equipped with valuable items to make such a massive link possible, was under attack. If they lost the equipment, they lost the chance to make the link. As the digital onslaught progressed, Meng and Ratoo caught a glimpse of their attackers. “There were four of them, and I had seen them before. They were from Nanjing,” Ratoo said. “They were pretty ruthless.”

One after another, the link amplifiers broke. The Enlightened agents vanished without the teams exchanging a word. There was nothing much to say: the nine Resistance players were stuck on an island in the middle of nowhere, with no way to make the link to Anchorage. Meng was crushed, and so were all the other agents. “I traveled from Beijing to Nanjing, and drove from Nanjing to Jiangsu, so across half an entire country for this plan. The people who went weren’t there for sightseeing,” Meng said. Forming her battle plan had been intense, and so was the realization that there was no way to pull that plan off. “We were all tired and beaten up,” she added.

What’s more, they all knew that it was no coincidence that the Enlightened had figured out their plans. “It had to be that someone from our side told [the Enlightened], either intentionally or by mistake,” Meng told me. “It had to be.”

“We have never deducted what happened,” Ratoo said. However, there were a lot of theories. Software vulnerabilities are what Meng tends to focus on. A lot of Ingress players are professional developers and programmers, and there was a rumor that Intel Maps, an app used by a lot of Ingress players to sketch out portal links, was vulnerable to snooping. It’s a more comforting explanation for Meng. A Resistance agent was careless, not malicious. But both she and Ratoo also admitted that they wondered if a Resistance player, maybe even someone who came to the island, had betrayed them. Ratoo has theories, but he didn’t want to discuss them with me.

The next day, the demoralized agents returned to the mainland. Meng participated for the rest of the Global Shards event, but with less fervor. No matter what had happened, players had violated the spirit of the game. If a slighted Resistance player had slipped some information to the Enlightened, that was disrespectful to the community. If an Enlightened player had taken advantage of a security vulnerability, that was also disrespectful to the community.

Her opinions on Ingress continued to shift, and in October, she had a sudden realization: She wanted to quit the game. After spending the day driving around the island of Hainan to perform Ingress missions, Meng was feeling listless. “I remember lying in my hotel bed and thinking about two things. The first thing was that I was going to get a new apartment and a cat. I thought I should stop traveling that much and put all that money into renting a better apartment and getting a cat,” Meng said. “The second thing was that I should uninstall Ingress, which made me do so much traveling.”

Meng played Ingress because she loved the detail work of planning operations, but the other players were what made those operations possible. Players weren’t just pieces on a chess board—they were real, and they were as committed as Meng was to taking the world of Ingress seriously. In fact, Meng met her boyfriend playing Ingress in 2017. But by the end, the Ingress community was taking more than it was giving. “I think [Meng’s] life is better without Ingress,” Ratoo told me. “She got something out of the game, and I congratulate her. But still, tremendous pressure shaped her gameplay.”

Games like Ingress only work when a group of people decide to accept a set of rules that are distinct from everyday life. In Ingress, players accept that every park and train station could be the site of an epic showdown, but that’s only the first step. The magic happens when other people accept that, too. When players feel like that magic is real, there are few limits to what they’ll do or where they’ll go for the sake of the game. When the magic dries up, there’s no reason to stay.

Today, Meng doesn’t regret her time playing Ingress. She also doesn’t regret leaving. Ratoo, Leon, and Nuo still play, and she keeps in contact with them through a private account on Telegram, a messaging app. They mostly talk about non- Ingress subjects. Sometimes Meng logs into her other Telegram account, the one she used when she was a dedicated player, to see if she’s missing anything. She never feels like she is. “[Ingress] was a good chapter but it was taking a lot of my effort that could have been better used elsewhere,” she said.

These days, Meng has also fulfilled the other thing she promised herself. She has a better apartment – and a cat named Cosmos.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.