The Anatomy of Empathy

Credit to Author: Shayla Love| Date: Tue, 07 May 2019 17:42:46 +0000

One morning in the winter of 2007, a medical student sprinted toward a code blue at the University of Miami Hospital. A man had collapsed in the waiting room.

Before the alarm sounded, the two men were strangers. Seconds after, 24-year-old Joel Salinas and the man having a heart attack became linked—not just by Salinas’s medical responsibility to try to save him, but by an incredible fluke of the brain that allowed Salinas to intimately experience what the man was feeling. Salinas has a condition called mirror touch synesthesia, which means, simply, that when he sees another person feel something, he feels it too.

“I felt my back pressed firmly against the linoleum floor, my limp body buckling under each compression, my chest swelling with each artificial breath squeezed into me through a tube, a hollow slipping sensation,” he wrote in his memoir Mirror Touch, published in 2017. “I was dying, but I was not.”

After a flurry of doctors and nurses spent 30 minutes trying to revive him, the patient was pronounced dead. Salinas stared at the body. “I lay there with him, dead,” he wrote. “The absence of sensations in my own body, the absence of movement, the absence of breath, a pulse, any kind of feeling. In my body, nothing but a deafening absence.”

“It was a moment of trauma for me,” he told me when we met last November in a hotel lobby in downtown Boston, near Massachusetts General Hospital where he is now a neurologist. “But by the time I had collected myself, I was really mad. I started telling myself if I’m going to be the best goddamn doctor I’m going to be, I need to figure this out. I cannot let myself be this unstable around patients.”

Now 34, Salinas is better at managing the constant barrage of other people’s sensations. Since his book was published, he’s been the subject of several articles that tout his mirror touch synesthesia as the reason he’s an excellent doctor, rather than being a hindrance to his work. As one reporter put it: “Because of mirror touch, he closely attends to his patients, leading to effortless empathy with their condition.”

Salinas’s condition might sound straight out of a sci-fi novel, but there is a potential neurological explanation that is very of this world: Mirror touch may be an exaggerated form of a process all our brains have—the ability to mirror, or somewhat simulate, what others are doing and feeling.

For most of us, this mirroring happens beneath the surface of our consciousness; Salinas’s brain appears to plumb those depths regularly. Mirroring might be an integral part of how all humans experience empathy, and studying mirror-touch synesthetes like Salinas could offer scientists a rare look into how that all-important emotional impulse works in our brains.

Empathy can seem like the touchstone to our humanity—the driving mental process behind good deeds, a necessity for building strong relationships. Yet empathy strikes as a limited resource in our current political and cultural environment. So many people struggle and fail to understand the perspectives of those whose circumstances differ from their own. The search for the biological mechanisms of empathy serves as a reminder: We are capable of imagining what it’s like to be someone else. It may, in fact, be our instinct to do so.

On a rainy and cold Friday afternoon, the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital was a frenetic mélange of people in pain. As Salinas walked by patients, he saw a man holding his stomach in agony, which made his own stomach feel uncomfortable, and another man who was asleep with a bucket near his face, causing nausea to hit Salinas’s body in waves. He works regularly on the neurological floor, and when he walks into a room with a person who has had a stroke, who can’t move their right arm, leg or face, a side of his body immediately feels limp too.

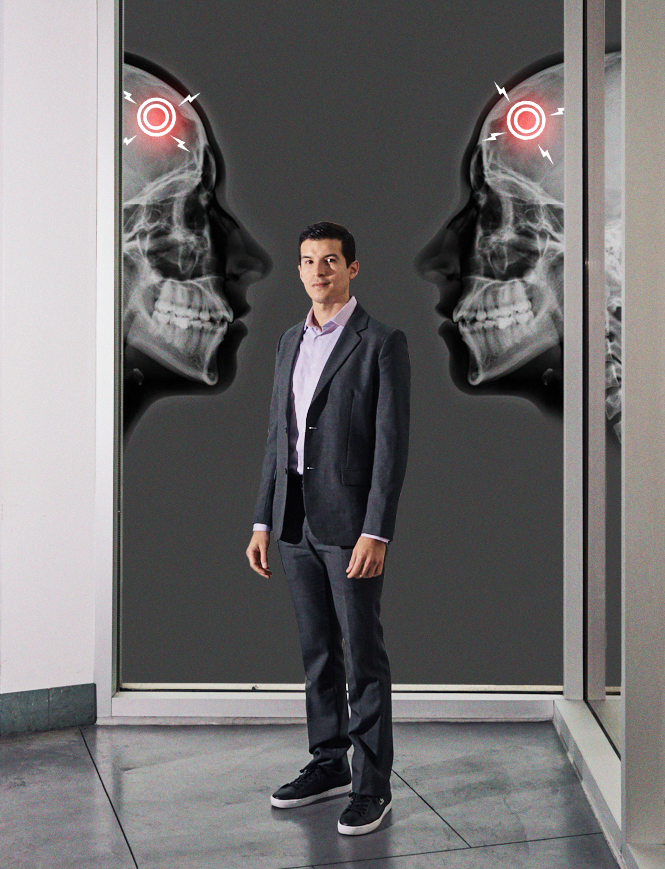

I watched as Salinas performed a neurological exam on a female patient who had been re-admitted to the hospital after having a bad reaction to medication following brain surgery. He was styled impeccably in a dark grey suit and lilac button down. His hair was slickly combed back revealing a friendly face that still shines with youth—if you didn’t know better, you might mistake him for an overdressed intern.

Salinas told his patient to move her arms and legs in certain ways, and checked her reflexes. Her hand flickered. “Do you usually have pretty brisk reflexes?” he asked her.

“I’m not sure,” she said.

He continued with the exam. He told her that her reflexes seem a little jumpy, and she said that the medication also caused some muscle cramping.

“I think it may still be some residual effect of the medication,” he said. “On this left hand it’s still slightly higher, slightly jumpier, compared to the right, which kind of makes sense in terms of your surgery.”

Satisfied, he moved on. He told me after that he could feel the change in reflex between her right and left side in his own hands, which helped alert him to the difference. Given the rest of her workup, he wasn’t concerned. Mirror touch also helps Salinas pick up on subtleties when he’s teaching. If a resident presented a case and he felt a tremble in their hand reflected in his own, he might be clued in to the fact that they’re feeling uncertain or nervous, and he can follow up with them later.

There’s been a move over the past decade to incorporate more empathy into medical training—to produce doctors who try to understand what their patients are going through, and express that while providing care. “The empathic component of medicine is what makes a physician special,” a medical student wrote in 2007 in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. Without it, doctors would merely be “highly trained computers.”

The human connection Salinas has to those around him is almost palpable. He is an extremely good listener, makes near-constant eye contact, and gives off a strong impression that he cares about what you say. There was a tingling eeriness to knowing—as many people do, with his book out in the world—that whatever I felt during our conversation, he felt too. I was aware of the times I was touching my face, or resting my chin on my hand, knowing that he was mirroring those sensations.

“It’s my brain’s automatic reflex to try to recreate the experience of another person based on my past experiences and the context, as best as it can,” he said. It’s clear that Salinas is an empathetic caregiver, and yet the exact connection between this automatic reflex he has and the complex emotion of empathy is still up for debate. When mirroring was first discovered in the brain, it was thought to be the holy grail that explained how we related to one another. But we may be finding that there’s more to empathy than just reflecting someone’s feeling back.

Empathy was first mentioned in a paper in 1967, when neuroscientist Paul MacLean called it “the capacity to identify one’s own feelings and needs with those of another person.” He urged scientists to study it, writing that empathy would be “a topic of critical importance for solving pressing problems of the modern era, including interpersonal callousness and aggression.”

Fewer than 20 years later, mirror neurons were discovered by accident in the brains of macaque monkeys. Scientists were surprised to find that the same neurons that were active when a monkey did something were active when they watched the experimenters doing the same thing (mirror neurons have also been called “monkey see, monkey do” neurons). The discovery presented the alluring possibility that our brains map others’ experiences onto our own. Scientists thought they might have solved the problem of how empathy works.

Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, known for his books on neurological case studies and work with phantom limbs, is largely credited with bringing mirror neurons out of academic obscurity. In an article from 2000, he wrote that mirror neurons would “do for psychology what DNA did for biology,” by providing a mechanism for traits and behavior that previously eluded explanation. There’s a direct link between empathy—the desire to understand and imitate each other—and the development of language and culture, he wrote. Language and culture are hallmarks of what separates humans from animals. Mirror neurons, therefore, were fundamental to our humanity.

Within a year of that article, “the use of the phrase mirror neurons more than doubled, and over the next decade, mirror neurons captured the public imagination, claiming to offer insight into everything from empathizing with therapy clients to international diplomacy, how children learn music, and how people appreciate art,” wrote Harvard psychology graduate student JohnMark Taylor in a blog post on the subject.

But just because we all have the ability to mirror the actions and feelings of others, doesn’t necessarily mean that mirror neurons are the essence of what it means to be human. Since mirror neurons’ discovery, the extent to which they explain complicated traits like empathy and altruism has been called into question, and theories that faulty mirror systems were a driving force behind conditions like autism have not panned out. There’s since been a scaling back on claims of a direct link between mirror neurons and empathy, but this cognitive process has continued to attract fruitful curiosity from scientists. If our brains are doing it, the thinking goes, it must have some purpose.

In 2005, researchers from University College London reported on a new form of synesthesia in which “visual perception of touch elicits conscious tactile experiences in the perceiver.” It was the first documented case of mirror touch; it’s now estimated that 1.6 percent of the population has the condition.

Their subject, called C, was an otherwise healthy woman. When researchers looked at C’s brain using fMRI, they found that her mirror system activations were higher than those of people without mirror touch. “The results suggest that, in C, the mirror system for touch is overactive, above the threshold for conscious tactile perception,” the authors wrote.

Just a few years later, in 2009, Salinas showed up at Ramachandran’s lab in San Diego. He had signed up to be studied as a synesthete for his lifelong associations between colors and numbers. He had also physically felt other people’s sensations since childhood, but hadn’t considered it to be that special. But Ramachandran knew just how unique Salinas’s condition was.

“He made the astonishing remark that when he watched somebody being touched, he felt the sensation in his own hand, or wherever they were being touched,” Ramachandran said.

Ramachandran knew it was likely that Salinas’s mirror system was somehow different from other people’s—and that his participation represented an opportunity to ask questions about the causal role of the mirror system and empathy.

“The thing with empathy is it’s related to so many constructs,” UCL neuroscientist Michael Banissy said. Banissy is one the leading researchers on mirror touch today, having studied more than 30 people who have it, including Salinas. “It’s related to sympathy, to compassion, but these are all slightly different to empathy in itself because empathy is purely the sharing of the experience. Then all these things come from it.”

Banissy thinks the implications of us having mirror neurons is important, but has been oversimplified. We now know that rather than specific mirror “neurons” that mimic behavior, he said, humans have whole brain systems that have mirroring properties, or are active both when we are touched and when we see other people being touched. The difference between a handful of neurons and a system is that it’s a larger, more dynamic process.

If you see someone being touched, it will activate similar parts of your brain as when you are touched. We know this. Brain imaging with fMRI has shown that mirror touch synesthetes over-activate this network, but that’s only one potential explanation for why they feel the touch of others.

In structural imaging research, which looks at the shape of brain areas rather than the function, people with mirror touch synesthesia exhibit differences in areas like the temporoparietal junction, or TPJ. This area, Banissy said, is involved in many things, one being that it’s associated with controlling “self-other representations,” or the ability to identify you as you, and someone else as someone else.

“Potentially [mirror touch synesthetes] have a general difficulty in inhibiting other people and they tend to treat other people’s bodies as if it’s their own,” Banissy said. “It’s what you might call a ‘self-other blurring.’ They’ve got a greater tendency to incorporate representations of others onto representations of themselves.”

When Abigail Marsh, a neuroscience and psychology professor at Georgetown, was 19, she was driving home late at night and a dog ran into the road. She swerved to avoid hitting it, spun out into the freeway, and found herself stranded in the fast lane with no phone. From the darkness, a man appeared who, “within a fraction of a second of seeing me stranded there, must have decided to pull his own car over to the other side of the road and then run across five lanes of freeway traffic in the dark to get to me,” she said.

He helped her to safety, got the car running again, and then said, “You take care of yourself,” and walked away. Marsh was stunned that someone could be so nice, at the peril of getting hit by a car themselves. “The reality that there are people who will risk their life to save strangers is sort of mind-blowing when you’re really confronted with it,” she said. Ever since, she’s dedicated her work to empathy and altruism—both qualities thought to be brought on by a blurring of the line between the self and the other.

Marsh studies groups of people who exhibit unusually high levels of altruism, like those who donate their organs to strangers. She’s found in multiple studies that when these organ donors watched someone else feel pain, they had similar levels of activity in the brain regions associated with pain as when they were feeling the pain themselves.

Marsh said that when scientists started to look at much bigger brain networks, they found something more than mimicry. Many neuroscientists now think of the brain as basically a predictive organ: It’s trying to find patterns in the outside world so as to stay just ahead of what’s actually unfolding in real time. When we interact with other people, our brains could be attempting to represent what’s going on in their minds and create a model in our own.

Marsh’s research has looked at the extent to which people are able to represent others’ emotions, like fear. An inability to do so might be a trait that leads to psychopathy. “People who are psychopathic seem to have a lot of difficulty internally representing other people’s fearful states, and the reason is because they have difficulty experiencing fear themselves,” she said. “So they aren’t able to create a good internal model of what somebody else’s fear looks like either. [That modeling] is sort of similar to the mirroring process. It is using your own experiences of that state to try to understand somebody else’s state.”

In her work with altruists, Marsh has found that they are better than average at representing other people’s fear. They are better at recognizing when other people are afraid, and the areas in their brains associated with fear react more strongly when they see others in fear. This is slightly different from the process for mirror touch, but Marsh thinks of it kind of like another form of mirroring. “We don’t exactly know how it works, but there does seem to be a sense of internal simulation happening there,” she said.

Mirroring alone does not lead to empathy. We still have to choose to believe another person’s feelings matter.

Other research has shown that when people interact with each other, especially with others they like, their brain activity starts to sync up. “[It] suggests that they are kind of modeling each other’s internal states, or their brain patterns of activity are becoming more similar during the interaction,” Marsh said. “What that helps produce is somehow related to good rapport. When people say something like ‘on my wavelength,’ that’s actually literally true.”

As we learn more about the biological constructs of human emotion, it turns out there may be a lot of ways to achieve empathy. Our brains may have more than one route to trying to guess and then simulate what’s going on in the mind of another. Still, Marsh thinks that while all these forms of simulation are important, we shouldn’t prescribe empathy as the only cure for all of our social woes. She accepts that it’s an important social tool, but not the only one.

Marsh hasn’t met Salinas, but said that the fact that he automatically feels others’ pain isn’t necessarily the reason he is a caring person. Empathy and care, though related, aren’t the same thing. “You can empathize with somebody else’s internal state, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you care about their internal state,” she said. “The urge to care about somebody’s pain or suffering seems to be sort of a downstream effect of empathy.”

Is the reason that Salinas decided to become a doctor, and is empathetic, because the feelings of others are pushed upon him? Maybe. But he also had to decide to care, and decide to make a career out of caring for others. Even without mirror touch, Marsh said, highly empathic people like Salinas are drawing on feelings of compassion for others.

Which is to say that mirroring alone does not lead to empathy. We still have to choose to believe another person’s feelings matter. In Salinas’s case, he sometimes has to scale his empathy back, so as to not be so overwhelmed that he can’t properly act on it; the rest of us might need to more consciously tap into it. We may not experience mirror touch, but it is our brains’ default to try and understand one another.

Often, people want to see something mystical in mirror touch, Salinas said, sitting in his tidy office about a 15 minute walk from the hospital. On the bookshelf are volumes about the neurobiology of synesthesia—literature that Salinas once turned to in order to learn about himself.

Since he also has “regular” synesthesia, his other senses blend together too: colors and letters and numbers, people and numbers, colors and smells. When people hear that he can feel others’ feelings, and see colors and numbers around them, they think he’s a mind reader or an aura reader, and ask him to say what “color” they are, like a parlor trick. “People really want this to be a psychic thing,” he said.

I’ll admit that after I read Salinas’s memoir, in which he described the people he meets by their synesthetic associations, I wanted him to “read” me. I wanted to know what colours and numbers I was, what his brain somehow came up with when he saw me. I too felt the desire to have him do his parlor tricks, for my own sense of selfish curiosity. That impulse made me think about how empathy doesn’t always beget empathy in return. People sometimes take advantage of him, he said, even if unconsciously. They open up to him, tell him their secrets, expect him to serve as a kind of therapist.

Salinas has struggled in his personal relationships. It’s easy for him to lose himself in a partner, and get wrapped up in their emotions rather than his own. He got married at 30, was divorced three years later, and said that with his ex-husband, the emotional boundaries got too blurry. It felt like his own mental map included his partner. When they got divorced, it felt like amputating part of his own body.

After his divorce, Salinas gave himself a year of not dating anyone. When he does go on dates now, people often feel a strong connection to him right away. “I know it sounds weird and arrogant, but when I say that, it comes from a neurobiological standpoint,” he said, laughing. “Imagine talking to somebody who’s like a super-active listener, super empathetic and is on the same page as you on a lot of things.”

It can be a self-perpetuating loop. If someone starts to feel attraction for him, Salinas could start to mirror it back—even if he doesn’t feel the same way—and it can snowball. If someone has recently been through something traumatic, it’s easy for him to get pulled into the emotionality of that and build a bond based on the sensations he’s mirroring.

Salinas now has tricks to not lose himself in what another person is feeling. He focuses on his own body and experience, or might physically stop looking at them. He does this when interacting with patients, too. It can be isolating, and at times he wishes he could talk about his condition more often—not as much about what he feels but about the colours and shapes that he regularly sees. But there aren’t many who understand.

He lives near a candy store, and sometimes when he walks by he’ll be hit with a wonderful sweet smell, and the synesthetic colors that accompany it. “I’m like, oh my God, that’s such a cool purple and yellow,” he explained. “I’ll take out my phone to take a picture and post it on my Instagram story and be like, oh wait, that’s not how smell works.” He can also sometimes slip up and remark that a colour was really loud or ask if others smell a particularly fragrant colour.

Salinas is just starting out in his medical and research career, and he’s not yet sure if he wants to center his research around mirror touch and synesthesia—though he does want to remain a study subject whenever his brain can be helpful.

Salinas wants to understand how social relationships influence health overall, and develop tools that can measure those effects. There are studies that look for patterns within social networks that have found that if you are obese, your friends and friends of friends are more likely to be obese. Same goes for happiness. He wants to see how social relationships affect brain volume, and the risks of developing cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s. This is, at its core, still about the ability of one person’s feelings, habits, and sensations to somehow rub off on another.

Many are surprised that Salinas would choose a life in which he is so vulnerable to the pain of others. But he doesn’t regret his choice at all. Since he’s felt people’s sensations since he was young, he takes it in stride. But he admitted that he does make an effort to sometimes indulge in the perks of mirror touch, without the pain. He recently started to do improv comedy for fun, where by coincidence, mirroring is a concept they teach. “If you walk into a scene, if you don’t know what to do, just start mirroring each other,” he said.

And being around laughter feels good—really good. “The feeling of people laughing has this quality of iridescent wild flowers,” he said. “These little flowers just turn their heads, patching all over the place and their actual petals have this iridescent kind of a multicolor quality to it. And it’s warm and great. I love it.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.