Hunting the ‘Beast of Buckland’: The Search for Linda Cook’s Killer

Credit to Author: Hayden Vernon| Date: Wed, 27 Mar 2019 12:54:50 +0000

Just after midnight on the 9th of December, 1986, 24-year-old bar worker Linda Cook was walking home through Buckland after visiting a friend. The area is a patchwork of estates in the middle of Portsmouth; only a mile from the sea, but you wouldn’t guess it if it wasn’t for the constant wind and the seagulls. They don’t put Buckland on the postcards.

Before Linda made it home she was raped, then stamped on so brutally that her spine was fractured and her larynx crushed. Her naked body was discovered the next morning, dumped on a patch of wasteland known as Merry Row.

Portsmouth has a reputation for violence, stemming from its military history. In reality, it is a city of petty crime and pub fights. Broken jaws and stolen purses are common – murder is not. More than 30 years on, Cook’s killing is still one of the most savage unsolved crimes in the city’s history.

Chris Clark was a good policeman, but his career in the force never quite hit the heights. A constable in Norfolk, in 1993 he applied for a position at the newly formed National Crime Intelligence service, where he felt he could put his intelligence gathering skills to use. Despite recommendations from his seniors, the then 47-year-old was turned down. His police career was curtailed and he retired the following year. His interest in solving crime would stay dormant for 16 years, before his second wife Jeanne reawakened it.

“In 2010 I was just enjoying retirement when she told me the story of nearly being abducted from a small village in Cambridgeshire back in 1971,” Clark tells me. “When I looked at the circumstances, I realised who she was talking about was [serial killer] Robert Black.”

Clark looked into Black’s movements around the time that Jeanne’s attack took place. Although he eventually hit a dead end, his interest in cold cases had been piqued. Now known as the Armchair Detective, Clark has written a number of books about murderers from the 1970s and 80s. “My aim is to make sure these cases are not forgotten and to give some sort of closure to the families left behind,” he says.

Clark’s research into serial killers and patterns of unsolved murders – skills honed during his time in the police – have made front page stories in the red tops and local newspapers. In particular, he picks up cases that the police failed to investigate properly at the time, which is how Linda Cook appeared on his radar.

Hampshire police reacted quickly after Cook’s body was discovered; they had to. Her murder came after a series of sex attacks in the area, and public pressure to catch the culprit – who had been dubbed the “Beast of Buckland” – was immense. They had a few clues, not least the imprint from the sole of a trainer reading “flash” that had been left on the victim’s stomach by her attacker.

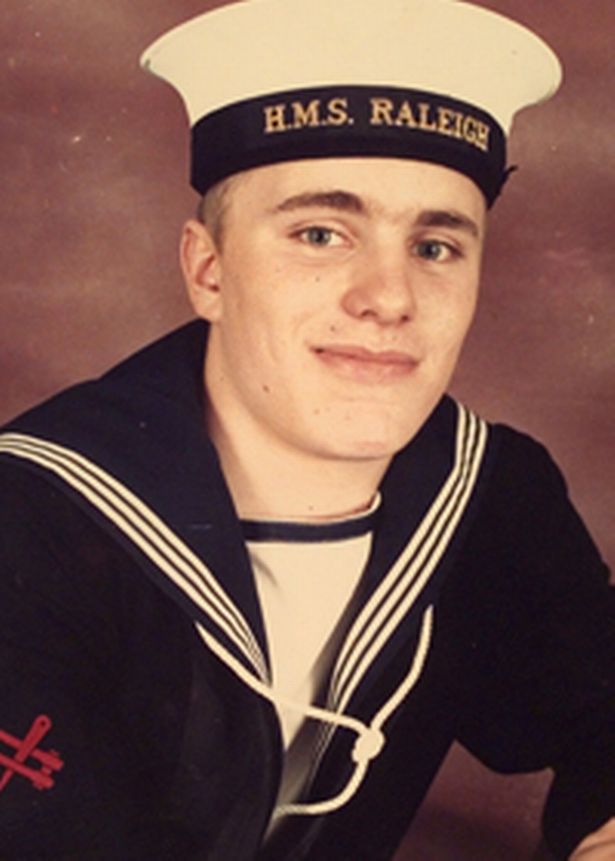

Michael Shirley, an 18-year-old Able Seaman stationed in Portsmouth at the time, owned a pair of those trainers. He had been drinking in Joanna’s the night of Linda Cook’s murder, a sticky-carpeted seafront club popular with sailors on shore leave who would try their luck with local girls. Shirley got lucky that night, almost, when a young woman called Deena Fogg agreed to take him back to her flat. They shared a taxi, but Fogg had a change of heart, mumbled something about having to collect her baby and left him in the car. The young sailor waited a while and then looked around for her, but she had ditched him. He walked back to the naval base with his tail between his legs and clocked in just before 2AM.

By chance, he met Fogg another couple of times before he was scheduled to sail out from Portsmouth for the Falkland Islands. On the second of those encounters, again at Joanna’s, Fogg pointed him out to the police and he was arrested for Linda Cook’s murder. The prosecution argued that he killed her in a fit of rage after being given the slip by Fogg that night after Joanna’s. DNA sampling was in its infancy at the time, but there was a partial match between Shirley and a sample found on Cook’s body. This – along with the fact he owned a pair of the “flash” trainers, and a period of half an hour that he was originally unable to account for – was enough to convict him and sentence him to life imprisonment, in January of 1988. He would go on to serve 16 years for a crime he did not commit.

“Once his name was in the frame and he was arrested, the police became blinkered, fitting the crime around him rather than seeing if he did in fact fit the crime,” says Neil Humber, a former journalist whose long campaign formed the basis of Shirley’s appeal, which led to his exoneration in 2003. “My subsequent investigation and the uncovering of a taxi log proved the police had quite simply ‘shifted time’ to fit their narrative.”

Shirley maintained his innocence throughout his time in prison, staging a protest on the roof of HMP Long Lartin in 1992, which then escalated to a full-blown hunger strike that nearly cost him his life. Before the appeal, a DNA sample taken from the scene was found for fresh tests, but Humber argues it was not forthcoming from the police.

“I did pester them on three occasions, asking if any forensic samples could be used to test for DNA,” he says. “Twice I was promised they’d look into it, and eventually I was told they’d all been destroyed. This was subsequently found to be untrue.”

When the police did find a sample, new tests revealed that Shirley’s DNA profile coincided with only one thin band – and that characteristic is shared by almost a quarter of British men. The rest of the DNA did not match either Shirley or Cook – and because the appeal judges accepted that there were not two attackers, Shirley could not have been the killer. He entered prison at 18 and left as a 34-year-old.

The case was reopened shortly after Shirley’s conviction was quashed, and Hampshire police appealed for new information. Chris Clark argues that because of their initial failings, the police have done little to shed light on the case since.

“They have never really bothered to progress this case,” he says. “This runs true to form with several miscarriages of justice which occurred around the country as early back as 1972-3.”

But researching Cook’s murder independently for a new book, Clark thinks he has a good lead on a potential suspect: convicted murderer and rapist, Paul Barry Taylor.

Taylor killed 22-year-old Sally Ann McGrath in 1979 after meeting her in a hotel bar. He brutally attacked her and dumped her body in a woodland. Like Cook, McGrath was murdered after a spate of sex attacks in the area she was killed in. “Linda’s murder is very similar to Sally Ann’s in Peterborough,” says Clark. “She was stamped on, really nasty injuries, well over the top.”

Taylor escaped justice for over three decades before it caught up with him in 2012, when he was sentenced to 18 years after being found guilty of McGrath’s murder, as well as three separate rapes, an attempted rape and a serious sexual assault committed in the lead up to the murder. Clark says that two weeks after McGrath’s murder, in September of 1979, Taylor attacked his 16-year-old sister-in-law, hitting her on the head with a tin of paint: “They couldn’t progress the attempted rape, but they did him for actual bodily harm and he went away to prison for two years.”

After he left prison, Taylor moved south, down to Fleet in Hampshire, then on to Fareham in 1985, a town just six miles away from Portsmouth. Clark says that a pattern of sex assaults followed him down the country, culminating in Linda Cook’s murder in 1986. Because he was under the radar for so long, even the police force responsible for bringing him to justice have admitted Taylor may have more victims.

“I think there’s every chance that there are women that we don’t know about who were victims of Taylor. I suspect, probably, rape. Whether there are any murders that Taylor was responsible for would be pure speculation,” Det Supt Jeff Hill told the BBC in 2012.

Clark argues the evidence he has dug out is more than mere speculation. After seeing a newspaper story floating the possibility of Taylor as a suspect, a witness emailed Clark to say he recognised Taylor from a picture in the article. The witness was driving home past Merry Row on the night of the murder, when he claims a man matching Taylor’s description ran out in front of his car. The driver stopped abruptly and the man stared through the windscreen before running off. The witness said he made a statement to the police about what he saw at the time, but it was never followed up.

Clark has urged the police to look into the possibility that Taylor is responsible. He thinks remaining DNA samples may only be partial and therefore not enough to link Taylor to the crime, but with numerous freedom of information requests turned down and little way of finding out what, if anything, the police have done to investigate his evidence, he has been left frustrated.

“I think Hampshire Police are trying to keep the lid firmly closed,” he says. “They don’t want to reinvestigate because it’s going to show they missed very good potential suspects in their wild chase to get a result.”

Hampshire police issued a statement, saying: “A review of all information and evidence available in the Linda Cook murder case is ongoing as part of regular routine work carried out by Hampshire Constabulary.” They declined to comment on the nature of evidence in relation to the case.

Chris Clark’s lawyer did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.