The Cash-Strapped Museum Embraced by Cops and Corporations

Credit to Author: Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard| Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2019 19:12:09 +0000

“Are you a law enforcement officer?”

That was a first. I hadn’t even made it through the doorway of my destination, a new museum working to “expand and enrich the relationship shared by law enforcement and the community” by providing visitors a “‘walk in the shoes’ experience” of what it’s like to be a cop in America.

“No, I’m not law enforcement,” I stuttered, caught off guard by the abruptness of the question. The man asking was a special police officer (SPO) who directed me through a metal detector I proceeded to set off. As he patted me down, a couple behind me responded affirmatively to the same question. Instead of dumping their pockets and bags on the X-ray conveyor belt and stepping through the machine, they were guided around the equipment, displaying their credentials and gliding down the stairs into the underground museum space.

I asked the SPO why current or former law enforcement agents are waived from inspection. “As long as they have valid credentials, they can come on in,” he responded. “This museum was built for them.”

Tucked into Washington DC’s Judiciary Square, the privately-funded National Law Enforcement Museum (NLEM) opened in October 2018 after nearly 20 years of planning. But devoting itself to a profession that has been the subject of decades of life-and-death criticism, hard-hitting reporting, federal scrutiny, and radical critique raised basic questions about the Museum’s purpose, and potential lifespan. Museums can have a range of goals, from remembering, to reconsidering, to reenforcing a particular message. It’s far from clear which of those aims the NLEM wants to embrace, and its public image may be destabilizing its financial future: Both visitor turnout and fundraising have been lower than anticipated, so much so that the Museum’s parent organization defaulted on $25 million in bonds less than three months after opening.

With $103 million in bonds and millions more in funding from industry giants like Target, Motorola Solutions, Verizon, and Glock, it’s hard to make sense of the project being so deep in the red. But according to a January investor meeting, 2018 fundraising efforts fell short, with the Museum scrambling to find almost $7 million in “unidentified major gifts.” The financial turmoil spurred by inadequate fundraising has been exacerbated by insufficient ticket sales: the NLEM attracted “nearly 15,000” visitors in the first three months, not nearly enough to keep it on track for its first-year goal of 420,000 paying visitors. To put this in perspective, DC’s latest addition to the Smithsonian, the much-heralded National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), opened in September 2016 and brought in 733,000 visitors in the first three months, hitting over a million within the first five months.

Executive Director of the NLEM Dave Brant attributes the low attendance to the time of year the Museum opened, arguing the fourth quarter of the year, a.k.a. autumn, is “always the lowest for tourism and Museum attendance in Washington, DC.” The original visitor projections were also formulated when they “did not know the completion date for Museum construction,” NLEM Senior Director of Communications & Marketing Steve Groeninger said in an email.

Yet the NMAAHC, an institution conveniently mentioned alongside the NLEM in a Target press release touting the retailer’s support for both, far surpassed its policing counterpart even when opening at the same time of year.

Groeninger went on to explain that the museums have “vast differences,” like “content, size, admission fees, [and] location” that account for this discrepancy. That much is for sure: the NMAAHC and the NLEM are undeniably different. The former encourages visitors “to participate, collaborate, and learn more about African American history and culture,” while the NLEM’s parent organization, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, aims to “inspire citizens to value and respect law enforcement.” Their shared sponsor, Target, exemplifies how a mainstream corporation can simultaneously finance one institution confronting police violence head-on, and another that simply acknowledges police-community “tensions.” As public scrutiny of law enforcement continues to ramp up, it remains to be seen if other potential donors of “unidentified major gifts” might steer clear of such a seemingly contradictory endorsement.

What’s odd about this big fundraising push is that a wide variety of companies and nonprofits are already funding the exhibits, and visitors are reminded of this at virtually every turn. I visited the NLEM on a dreary Thursday afternoon in late January. I had been intrigued by the Museum since it opened in October, but its default was what really piqued my interest: could it be that the strength of corporate support might not be enough to keep afloat an institution honoring a profession that Americans, especially people of colour, regard with skepticism?

For six hours, I wandered the dimly-lit underground exhibit space that featured a police car, a body-cast K-9 dog, Osama Bin Laden’s pakol cap (which, according to the artifact’s description plaque, had been stolen as a trophy by a Navy SEAL), J. Edgar Hoover’s original desk, and two levels of cell bars donated from the now-closed Lorton Correctional Complex in Virginia. It was over 50,000 square feet of silence broken by occasional whispers from the handful of visitors I saw that day and the squeaks of an un-oiled escalator. Besides my conversations with Museum officials, the only consistent sound was melancholic piano that hovered in the exhibit space, which is essentially one large room and a few offshoot nooks.

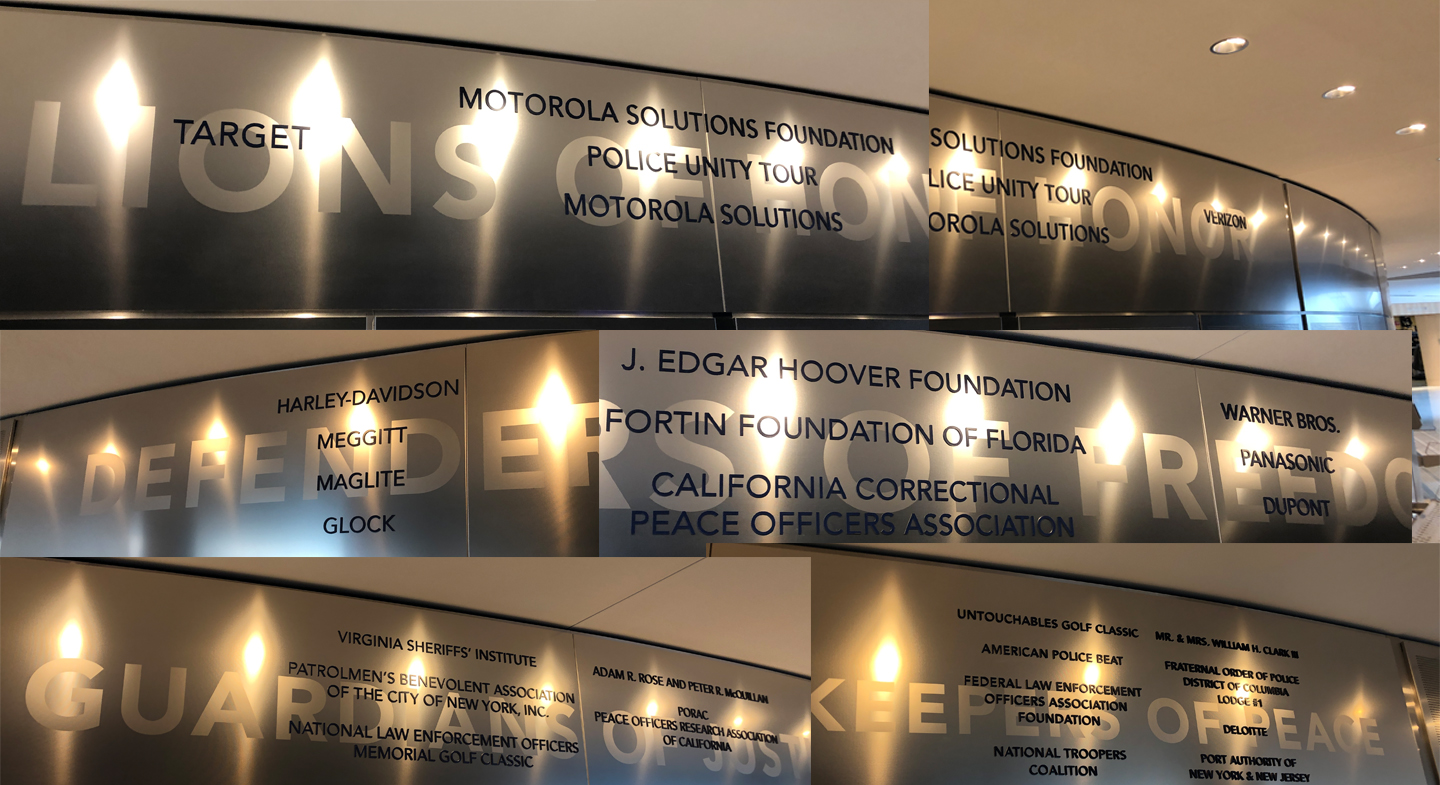

Entering the exhibition area, I walked alongside a curved wall decorated with plaques and raised letters saluting the long list of private donors. Beyond the mounted glass sheet engraved with donor names, the more elite contributors were prominently listed, their regal donor levels printed behind their names. The top status, “Lions of Honor,” is awarded to organizations that donate a minimum of $3 million, including Target, Motorola Solutions and its Foundation, and the Police Unity Tour; the latter’s stated purpose “is to raise awareness of Law Enforcement Officers who have died in the line of duty.”

The next class of donors, “Defenders of Freedom,” requires donations between $1 million and $2,999,999. Verizon Wireless, the gun company Glock, the California Correctional Officers Union, Kevlar manufacturer DuPont, Harley-Davidson, and Warner Bros. are among the companies that earned that classification. The other, lower categories are “Guardians of Justice” and “Keepers of Peace.” The donors, their levels, and corresponding donations are all compiled for curious visitors at the end of a walkway with a touch-screen kiosk.

Beyond cash donations, Target also provided pro-bono construction and design services, and Motorola Solutions supplied “state-of-the-art communications and video surveillance solutions.” Many other companies offered similar in-kind donations, like the artifacts populating the Museum’s collection: a Bell helicopter that hangs above the exhibition space, or a MAGLITE-brand flashlight that deflected an AK-47 bullet from wounding an officer’s chest and is housed in the “Tools of the Trade” exhibit, also sponsored by the flashlight company.

That touch-screen kiosk identifies each company’s sponsored exhibit. But visitors don’t need to read that list to notice the corporate influence present; the Museum makes that readily apparent with its logo-covered exhibits.

Of course, it’s not unusual for museums to receive private donations, both direct and in-kind. Look no further than the Newseum, another DC-based private institution dedicated to “increas[ing] public understanding of the importance of a free press and the First Amendment.” Like the NLEM, it boasts a wide array of corporate sponsors from the industry it represents—in this case, news media. While the NLEM has the support of tactical gear companies, the Newseum has The New York Times and Hearst Corporation. The NLEM has a Glock-funded history exhibit; the Newseum has the permanent “9/11 Gallery Sponsored by Comcast.”

But what seems to set the NLEM apart is the blatant, and even aggressive, corporate marketing that pervades its exhibits on law enforcement—a supposedly public, governmental service. One such sponsor that makes their presence loud and clear is Motorola Solutions, the public safety-oriented sibling of the better known consumer cell phone company, Motorola Mobility. Geared towards “mission-critical” technologies for industries like EMS, hospitals, and law enforcement, Motorola Solutions serves up products like walkie talkies, 9-1-1 call software, and its recently introduced line of body-worn cameras, a piece of tech that has come to be a pivot point in the national response to police shootings of unarmed black men. Motorola Solutions donated over $18 million in total to the Museum, and prides itself as “the Museum’s first founding partner.” Their mark can be seen before visitors even enter the place: the street-facing glass pavilion wall of the Museum announces that the NLEM is “at the Motorola Solutions Foundation Building,” paid for by the telecommunications company’s philanthropic arm. Inside the Museum, employees and volunteers hang lanyards around their necks that are threaded with the company’s logo, a blue circle with an “M” in its center.

Within the airy gallery space, the words “Motorola Solutions” glow in a luminescent sign above its sponsored exhibit, 9-1-1 Emergency Ops, and on the interactive screens, reminiscent of a Best Buy store display. 9-1-1 Emergency Ops shows visitors the “real-life intensity of a public safety command center” by exploring its branded “two-way radio communications systems” and “public safety software, including emergency call-handling solutions.”

Motorola Solutions did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. But another corporate marker on display throughout the Museum is Target’s bullseye logo. Sponsoring all the Discussion events in the Verizon Theater, the retail giant branded the theater’s podium and slideshow title pages.

Additionally, Target sponsors its eponymous exhibit, “Target Take the Case,” which offers visitors an interactive experience to learn about law enforcement and forensic lab collaborations. Like Motorola, Target is plugging services offered by their company. Still a low-profile department nestled within their broader business, Target’s in-house forensics labs quietly operate in Las Vegas and Minneapolis. Originating in response to “retail-theft gangs,” Target’s asset protection department developed the lab in 2001 to assist their internal shoplifting investigations with video, fingerprint, and computer analysis that would otherwise be delegated to law-enforcement agencies.

As its reputation spread, the forensics lab took on “felony, homicide and special circumstances cases for law bureaus that need[ed] the extra manpower, facilities, resources and time.” 20 percent of the forensic services’ caseload is pro bono work “to assist law enforcement on cases unrelated to Target free of charge to alleviate strain on our law enforcement partners’ resources,” Target’s senior director of communications Joe Poulos told VICE.

Target’s avid support for a law enforcement museum, or even law enforcement in general, may come as a surprise to consumers who associate the store with college dorm gear and home appliances. But “In many ways, Target is actually a high-tech company masquerading as a retailer,” Nathan K. Garvis, Target’s former vice president of government affairs, said in a 2006 Washington Post interview. By this, Garvis was alluding to Target’s already extensive forays into collaborating with and extending the reach of law enforcement. Target’s Safe City program, designed to “foster partnerships between local police and community members,” has been touted as “expand[ing] the reach” of “broken windows” policing, a practice notorious for often seeming to criminalize poverty by targeting “quality of life” crimes like trespassing, loitering, and possessing small quantities of marijuana, among others. The company also runs “investigation centers” that share information with law enforcement, including surveillance from store cameras—many of which now employ sophisticated biometrics. Target also finances public surveillance infrastructure in urban areas nationwide. The retailer’s initiatives, including the forensics service represented in the NLEM, blur the lines between corporate and state surveillance.

Poulos declined to comment on the total amount donated by Target to the Museum and the Memorial Fund.

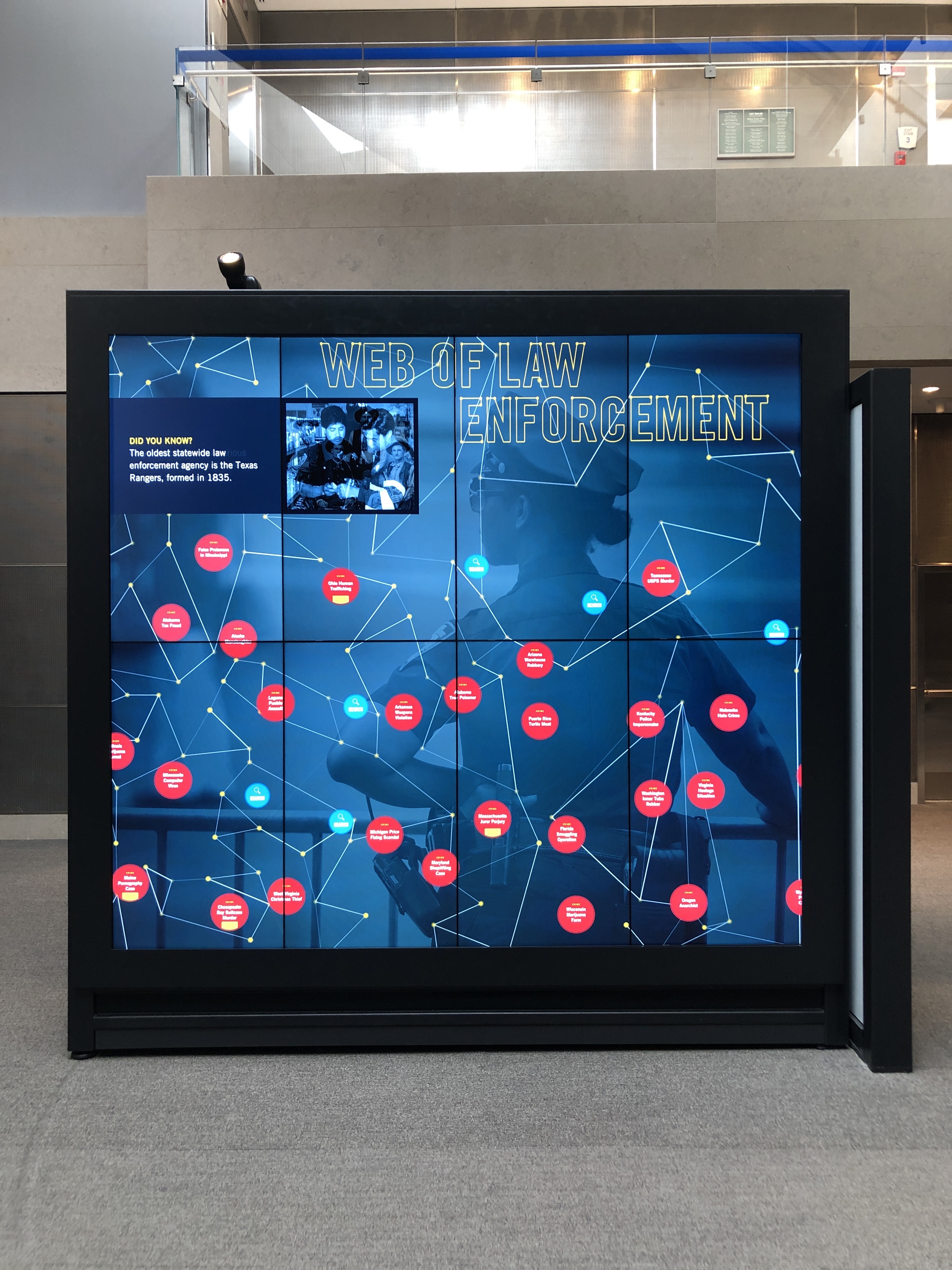

The list of mainstream brands goes on. AT&T paid $1 million to sponsor the Web of Law Enforcement, an interactive display showcasing the communication company’s post-9/11 private-public partnership that created a broadband network exclusively for first responders and law enforcement. DuPont’s Kevlar brand, practically synonymous with body armor, funded a self-named gallery that includes rotating exhibits curated by the Museum itself. Currently, the gallery houses “Five Communities,” which features different case studies in officer-community relations.

Sponsoring an exhibit that takes on the relationship between the police and the policed may seem like an odd choice for a company that makes bullet-proof vests. But as a DuPont spokesperson told VICE, the materials company did not plan the exhibit in the first place. Instead the Museum curated it, and DuPont was given the opportunity to sponsor it.

“Five Communities” does not mention police killings of unarmed civilians, or other combat circumstances that may call for use of DuPont’s products. Instead the exhibit highlights nonprofit organizations that “are analyzing the root causes of violence and of hostility to law enforcement,” like Project Unity, a Dallas organization formed in response to the July 2016 killing of five metropolitan-area police officers. Racial bias and police officers’ excessive use of force are not listed as factors in tumultuous community relations.

This curatorial decision is not much of a surprise. The Museum isn’t meant to focus on “current national politics,” the NLEM’s lead director of exhibits and programs, Rebecca Looney, told the Architect’s Newspaper. In other words, Black Lives Matter—and the president who ran in reaction to it—might as well not exist.

The DuPont spokesperson declined to specify the total financial value of their donations, but noted DuPont sponsorship of the rotating exhibits would expire in two years.

The NLEM’s journey began in 2000, when Bill Clinton, a leader known for his escalation of tough-on-crime policies, signed the law authorizing its construction on federal land. The Memorial Fund was required to begin construction exactly ten years after the law was enacted—a goal it missed. Twice.

The first time around, the Memorial Fund failed to secure bonds—the ones that are now being defaulted on—because of “current economic conditions,” according to a Senate committee report. Even after the Museum symbolically “broke ground” on construction in a ceremony headlined by former US Attorney General Eric Holder and former Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano a month prior to the deadline, Congress extended the construction date to November 2013, given the Memorial Fund’s budgetary revisions, which included slashing construction costs from “$80 million to $51 million” and cutting the building size roughly in half.

But three years came and went, and the Memorial Fund still did not have enough funding to initiate construction. Back in Congress, a House committee report found that “additional time [was] necessary to secure the non-federal funds to construct” the Museum. The deadline was once again extended by another three years, now to 2016.

Nearly two decades after its original authorization—years dense with popularized anti-racist social movements, like Black Lives Matter, and increasingly-mainstream debates on police violence—the NLEM opened its doors to a crowd comprised largely of those in the profession of policing, according to the observations of both Alan Davis, one of the Museum’s staffers, and the SPO who welcomed me into the building. Similarly, Washington Post reporter Sadie Dingfelder noted last month that “the place was buzzing—largely, it seemed, with people who work in law enforcement and their families.”

“Even as a former Seal commander, I don’t think I’ve ever felt more safe. One, [because of] the men in blue before me,” then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke said at the Museum’s opening ceremony. “But the opening of this monument and museum is really a testament to how much our law enforcement are [sic] loved. America loves you.”

TripAdvisor and Yelp reviewers of the Museum, several of whom self-identify as members of “law and order families” and “law enforcement families,” express sentiments similar to Zinke’s: their relationship to, and understanding of, law enforcement is validated, not complicated, by their time there. In other words, it’s not a place many people seem to be going to question their own worldview.

Groeninger pushes back, however, against the idea that only people connected to law enforcement were visiting. “Two weeks ago, we had nearly 700 visitors attend our Family Fun Day event that focused on the working world of K9s,” he said in response to a question about the types of visitors coming through the Museum’s doors. Precise breakdowns of how many visitors were police-affiliated were not recorded, but Groeninger added that “there definitely appeared to be a mix of both law enforcement and non-law enforcement attendees.”

In contrast to the SPO’s take, Groeninger went so far as to emphasize that “the Museum is geared primarily to those not in law enforcement,” noting it targets everyone from educators to the general public. The Museum is “confident that receptions, tours, [and] school groups” will boost visitor growth in 2019, according to Brant—even though it dropped its visitor goal for this year by 120,000 paying visitors, aiming for 300,000.

But the low ticket sales, alongside their missed targets for “major gift fundraising,” have amounted to serious financial setbacks for the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, the Reagan-era nonprofit organization running the Museum, jeweled with conservative cop icon Clint Eastwood as its Honorary Chairman and the former attorney general John Ashcroft, who worked to justify torture in the Afghanistan War, as its regular chairman. It was in early January that the Memorial Fund defaulted on $25 million in institutional bonds that were helping fund the place. To offset the growing budget shortfall of both the Museum and the Memorial Fund, ticket prices have been hiked a dollar, to $21.95 for adults, $14.95 for children, and $17.56 for law enforcement, a rate that has been labeled as unreasonable to some visitors, many of whom are likely used to the free Smithsonian museums that abound in DC. More significantly, the Museum is doubling down on fundraising and aims to secure $29 million in 2019—though where they’ll get at least $6.9 million of the needed funds remains to be seen.

The training simulator donated by Meggit Training Systems was the last stop on my Museum tour. Equipped with an interactive gun, taser, and pepper spray, participants are presented with VR-like videos that screen potential policing encounters. They range from shoot-outs, to drug busts, to interventions for people with untreated mental health issues, who are 16 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement. During my visit, Museum staffer Davis, a former NYPD detective and now a docent manning the simulation, sat down with me in the dark room, swiveling back and forth between a computer controlling the hundreds of available simulations and our conversation about visitor reactions to being “in the shoes” of an officer.

Some are quick to shoot a suspect. Others are more hesitant, sometimes raising questions and concerns about officers’ use of force. Davis initiated a simulation that confronted me with a bloody-faced woman who had been assaulted by her muscly, hammer-wielding husband. I giggled uncomfortably—mostly surprised by the extreme situation that was pitched to me as a “day in the life of an officer,” but also because I was unsure of how to react, especially given that the situation seemingly demanded the use of my weapon.

Some have found the situation less daunting. Fox News’ Judge Jeanine Pirro (whose show has since reportedly been suspended) was presented with the same scenario in a January broadcast report. In it, she confidently wields the gun prop, swiftly commanding the simulated suspect to drop his weapon.

For Meggitt Training Systems president Jeff Murphy, the simulator is intended to help the Museum “accurately portray the vital role of police officers in daily life.” But for Davis, it shows visitors that policing can boil down to a “person holding a loaded gun and shooting another person.”

Davis makes clear a point that the Museum seems to tiptoe around: police kill people. In the Hall of Remembrance, a solemn room sponsored by the Police Unity Tour, the NLEM honors officers killed in the line of duty, clearly a key part of the Museum, given that its parent organization, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, operates the official national monument dedicated to memorializing officers who “have made the ultimate sacrifice for the safety and protection of our nation and its people.”

But when asked about how victims of police shootings might fit into the Museum’s memorializing exhibit, Davis answered, “It’s not law enforcement’s job to build a memorial for people killed by the police.”

Groeninger, the spokesperson for the Museum, said something similar.

“Representing ‘victims of police’ violence is not part of our mission,” he wrote. “Our mission is to tell the history of American Law [sic] enforcement and provide a platform for thoughtful dialog involving diverse points of view.”

But police officers’ use of force, especially as directed towards communities of color, seems like a key part of the profession’s history. Black feminist activist and scholar Angela Davis argued in an interview in 2014 with The Guardian that “There is an unbroken line of police violence in the United States that takes us all the way back to the days of slavery, the aftermath of slavery, the development of the Ku Klux Klan.” Long before Michael Brown was a slain teenager every American seemed to have an opinion about, a 2006 article in the Journal of Criminal Justice Education supported Davis’s take, writing that “the similarities between the slave patrols and modern American policing are too salient to dismiss or ignore. Hence, the slave patrol should be considered a forerunner of modern American law enforcement.”

But as illuminating as they are, insights into the history of modern policing are not required to understand how anti-black and racist violence shapes the state of law enforcement today. Instead, the everyday encounters of a 21st century American police officer sometimes come down to “shooting another person,” as Davis, the simulation instructor, reminded us. The unavoidably violent portions of the law enforcement profession makes it hard to square Groeninger’s insistence on the Museum’s purpose with the scene on display. If the Museum aims to engage multiple, differing views on the reality of law enforcement, why is the vantage point of those criminalized and victimized by police absent?

I am not the first to bring up these issues. An NPR report published shortly after the opening criticized the “museum’s only direct mention of an officer-involved shooting” for mostly discussing “body cameras—how they became more popular after black 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white policeman in 2014.” The NLEM’s treatment of Black History Month similarly skirted the issue of violence directed towards black bodies: the Museum put a spotlight on African American representation in the police force, yet made no mention of those murdered by police officers. “Given the rise of the #BlackLivesMatter movement and the fact that minorities have been preyed upon by law enforcement (consciously or unconsciously), I think the museum could have done a better job of honoring that fact,” wrote a Yelp reviewer.

I asked Davis, who had been eager to answer my questions, what he might say to someone who raises concerns about racial bias in officer shootings. His response: “I can’t comment on that.” Similarly, while sitting down with Adult and Family Programs manager Alyssa Foley, who readily spoke with me about her work and the Museum at large, I posed the same question. She paused, appearing to ponder her answer. Her response: “I don’t think I have anything to say about that.”

Sponsors like DuPont, Verizon, and the museum itself declined to comment on the status of law enforcement’s violent relationship with the communities who experience actual policing.

Racism and police violence seem to be taboo subjects for the NLEM. “As soon as certain people hear Black Lives Matter, they react one way or the other,” Brant told NPR. “It creates a difficult setting to have a fair and objective and productive conversation.”

Groeninger reiterated that the Museum’s “mission is to tell the history of American law enforcement and to provide a platform for thoughtful dialogue involving diverse points of view. This may include topics involving Black Lives Matter and police-involved incidents; however, it’s important for us to cover those topics in a balanced manner appropriate to our role as a Museum.”

But this lack of “larger context,” Post reporter Dingfelder wrote, makes the NLEM more “propaganda than education.” The NLEM is designed to give visitors a “walk in the shoes’ experience, and it seems that most visiting enjoy being in a cop’s shoes; plenty others, however, don’t make it to the door. And the Museum doesn’t seem to be planning any changes to its content in the near future; instead, its operators are looking to “unidentified” corporations and wealthy individuals to continue funding operations.

This does not make the NLEM unique. Private museums, especially amidst DC’s diverse museum landscape, have difficulty staying competitive. Consider, again, the Newseum, an institution comparable to the NLEM for spotlighting a topic heatedly trending in national discourse. The Newseum has one of the highest museum ticket prices in the District at $25 (though they’re currently discounted 15 percent). Even in 2017, the year Newseum scored its highest attendance, it fell short of its goal by hundreds of thousands of visitors. Such problems mean the Museum has been beset with severe financial issues since moving to its new $450 million building in 2008, mere blocks from the NLEM. It has also struggled with its content, such as how to tackle big issues in journalism; in August 2018, the Newseum came under fire for selling now-removed “fake news”-themed apparel, alongside Make America Great Again hats.

The Newseum may be a ghostly premonition of the NLEM’s potential fate. Caught between objectivity and financial solvency, between a founding purpose and the actual execution of that vision, it has been unable to coherently counter Donald Trump’s claim that journalists are the “enemy of the people.” That’s a formulation some leftist prison and police abolitionists might apply, in their own words, to law enforcement. Yet the NLEM valorizes law enforcement as clean heroes, with little to no room for a contrary narration. That messaging may not satisfy the number of people required to keep it afloat.

If the NLEM does go under, it won’t be alone: The Newseum is slated to close next year.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Sessi Kuwabara Blanchard on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.