Prison Escapees Describe How They Did It

Credit to Author: Nick Chester| Date: Mon, 11 Mar 2019 13:10:48 +0000

Prisons, by design, are difficult to escape from. So how do so many people manage it?

In the UK, there were 13 fully-fledged jail breaks and 139 absconds in 2017-2018 alone, the former involving overcoming physical restraints or barriers, the latter entailing doing a runner without the need for smashing, cutting or tunnelling through anything.

To find out how inmates plan and orchestrate jail breaks, I spoke to three escapees: reformed heroin smuggler David McMillan, Glaswegian gangster John Steele and former weed dealer Scott White.

John Steele

While in HMP Barlinnie, I planned to break out with my brother Jim and our friend Archie. There was a metal grate on the ceiling of a room on the top floor that was used to regulate the heating of the water, so we decided we were going to cut through it and go through the roof. The problem was that we were high-risk prisoners, which meant we weren’t allowed to be housed on the bottom landing in case we tunnelled out, or the top one in case we broke out through the ceiling. Me and Jim were in cells on the second landing and Archie’s cell was on the third. We were already under suspicion because we’d been involved in an escape attempt together in another prison, and knew we’d draw the attention of the guards if we all walked up onto the top landing together.

Fortunately, a room on another landing was connected to the room with the grate via a 12-inch-wide shaft filled with piping, providing me with a means of surreptitiously sneaking up to the top floor. Jim and Andy pulled me up from above and we made our way through a hole in the the grate, which had already been cut by other inmates with a hack-saw we’d had smuggled in. We ended up in a space between the ceiling and the roof. There was a door leading to the roof, which I managed to get open.

We’d arranged for some friends to have a car waiting for us outside the prison and pass us a mountaineering rope to scale the walls. Our pals strolled brazenly into the gardens of the screws’ quarters and attached one end of the rope to the pole their washing line was hung from. I threw a reel of tape we’d stolen from the prison textile shop down to them from the roof while holding onto the other end of the tape so they could attach the rope to the reel and I could pull it up. We then abseiled down the rope, jumped into the car and made out getaway.

The authorities thought we’d bribed prison officials, and put the word out that they’d make sure we had immunity from the wrath of the screws if we told them which ones were involved. The fact they were convinced we couldn’t have broken out without a crooked screw being involved is testament to what a well-orchestrated escape it was.

David McMillan

I made my decision to escape not simply to gain freedom, but to avoid a near certainty: execution. Imprisoned in Bangkok, I was nearing the end of a two-year trial. My lawyer told me it’d end in two weeks and that I’d be sentenced to death. I had to act fast.

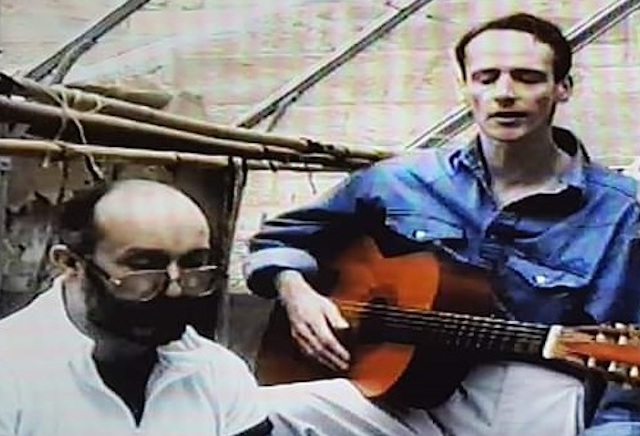

Just after midnight, I cut through my cell bars. A friend had mailed me four hacksaws concealed in a religious scroll inside a care package. I then used the linen tape of my mattress frame as a rope and slid down it into the grounds. I crept straight to the work sheds, grabbed some tools and built two ladders out of wooden picture frames, bamboo poles and gaffer tape.

Hauling the ladders over six internal walls to the outer wall meant crossing an open sewer and keeping between the guard towers. Dawn was breaking as I picked my way over the electric wire. I climbed out of the moat, where I’d landed, cleaned myself up and changed into civilian clothes. I then took at taxi to a nearby apartment, where a friend had hidden a forged passport and some bank cards.

At the airport, one of the ATM cards failed, so I could only fly as far as $500 would take me. The plane door closed just as prison guards arrived at Bangkok airport to look for me. Two hours later, safe in Singapore, I changed passports, checked into a hotel and immediately went to the rooftop pool. It was the best swim I ever had.

Scott White

In 1988 I was sentenced to four years in a Kuwaiti prison. It was good timing, because two years later Iraq invaded Kuwait, there was an extremely exciting jail riot and we all escaped. On the day of the invasion I awoke to the sound of silence, which was unusual. “What’s going on?” I asked my cellmate, Ali. “The Iraqis have invaded,” he replied. I turned on the radio to hear a news reporter describing how 100,000 Iraqi troops had crossed the border.

The main invasion route was half a mile away from the prison, so I was worried. The tension in the jail rose until it reached fever pitch, at which point an inmate booted the door off our block. Shortly afterwards, the prisoners from the block went to the part of the jail where political prisoners were housed, and freed them. This was the section where the “Kuwait 17” terrorists supposedly responsible for the bombing of the American embassy in Kuwait were kept. Almost as soon as they were set free, they coordinated attacks on the guards. Being of a slightly mellower constitution, I broke into the prison store, stole an ice cream and went out to catch some sun, which I hadn’t been out in for over a year.

The other inmates destroyed the paperwork so that there were no records of who’d been imprisoned there. Bullets flew about as the guards tried to contain the riot. They killed two prisoners, but eventually fled. We broke a hole in the jail wall and ran to freedom. Ali knew some people who lived relatively nearby, so I accompanied him to their house. I later hitch-hiked back to a friend’s place. The excitement had been intense; one minute I was facing years of boredom, and the next I was involved in a jail break into a war zone.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.