Convicts Explain Why They Would Rather Be in Prison Than Wear an Ankle Monitor

Credit to Author: Johanne Ramskov Erichsen| Date: Fri, 08 Mar 2019 15:37:07 +0000

This article originally appeared on VICE Denmark

Paulo Kongsbirk has multiple convictions on his record, eight of which are violence-related. Before his most recent sentencing, the 39-year-old was able to show that he’d broken away from his criminal connections – and also that his wife was pregnant – so was allowed to serve his time at home with an ankle monitor, rather than in prison.

However, serving his sentence in the comfort of his own home proved more difficult than he’d imagined. So one day, Kongsbirk cut off his tag so the police would send him back to jail.

“I’ve been a street punk my whole life and I’ve always found it difficult to put that way of life behind me,” Kongsbirk tells me. “It was hard for me to live a normal life as a parent. I needed to go back to prison to get some peace and quiet. There, I could sort myself out before returning to society.”

Back in jail, he knew where he stood. “I just felt more comfortable there,” Kongsbirk explains. “In prison, everyday life is structured, and the days pass along quietly. There are regular meals and lots of other people around.”

Kongsbirk isn’t the only convict who has longed to return to his cell. In 2017, according to figures from the Danish Prison and Probation Service, 2,107 offenders were offered the opportunity to serve their entire sentences wearing an ankle monitor. In 396 cases, the arrangement was cancelled and the offenders were returned to prison; 95 requested to be sent back, while the remaining cases involve offenders who violated the terms of the agreement in some way, such as by drinking alcohol or leaving their homes without permission.

According to the Danish Prison Officers Union, Danish prisons have reached maximum capacity, and in most prisons inmates are forced to share cells. That’s why the ankle monitoring system offers much needed relief. Since the practice was implemented in 2015, around 20,000 convicted felons have served out some portion of their sentences with a tag.

Now, regardless of the crime they are convicted of, prisoners who have been sentenced to six months or less are given the option of serving it from home with an ankle monitor. Unless, that is, they have no permanent address, as the Danish Prison and Probation Service is required to monitor your movement and whereabouts. Another condition is that convicts must be enrolled in an education course, have a job or occupy their days in some other structured way. Consuming alcohol and other substances is forbidden, with the prison service carrying out random searches and taking urine samples to ensure compliance.

Kongsbirk has now completed his most recent sentence, and hopes it will be his last. He’s currently working as a painter’s apprentice – the first non-criminal job he says he’s ever had. However, should he ever commit another crime, he has no doubt that he’d rather serve the sentence in prison.

“I don’t want to wear an ankle monitor again. I’m old and at a point in my life where I would prefer serving a sentence in prison,” he explains. “I know all the rules there, and if you just relax and keep your head down, time passes by quickly.”

Brian Levy Petersen, 37, has completed most of his two-year prison sentence for a drug-related crime and is currently serving the final four months of that sentence wearing an ankle monitor at home in Christiansfeld, southern Jutland. “Next week, I will start the part of my sentence where I only have to stay at home at night,” Petersen says. “I look forward to eventually being able to take my son to football practice and have a beer on the couch at night after the kids are in bed.”

Normally, Petersen conceals his ankle monitor with his sock, but that’s a challenge if, for instance, he’s only wearing trunks. A couple of weeks ago he took his twins to the local public pool and other parents couldn’t help but stare at his tag. The chlorine in the water also caused a malfunction in the device, so he’s been fitted with a new one. He still has a few more months to go, and he doesn’t like it to be too visible. It’s embarrassing, he says, making his life a lot more difficult than if he was just in a cell.

“In prison you can move around and work out; generally spend your time how you see fit,” he explains. “Some inmates treat prison like it’s a holiday of sorts. Wearing an ankle monitor means that you are confined to your house. At home, you can’t drink or do drugs.”

Brian’s daily life with his ankle monitor is scheduled to the minute. He gets up in the morning and helps his children get ready for school. From there, he has 50 minutes to get to work. If he arrives early or late he is required to report it to the authorities. At the end of the day he has to return home in the allotted 50 minutes and check in, before he can even consider using some of the four hours a week he’s been given for running errands. On weekends, he has 16 hours of free time in total. He tells me that he spends that time hanging out with his kids.

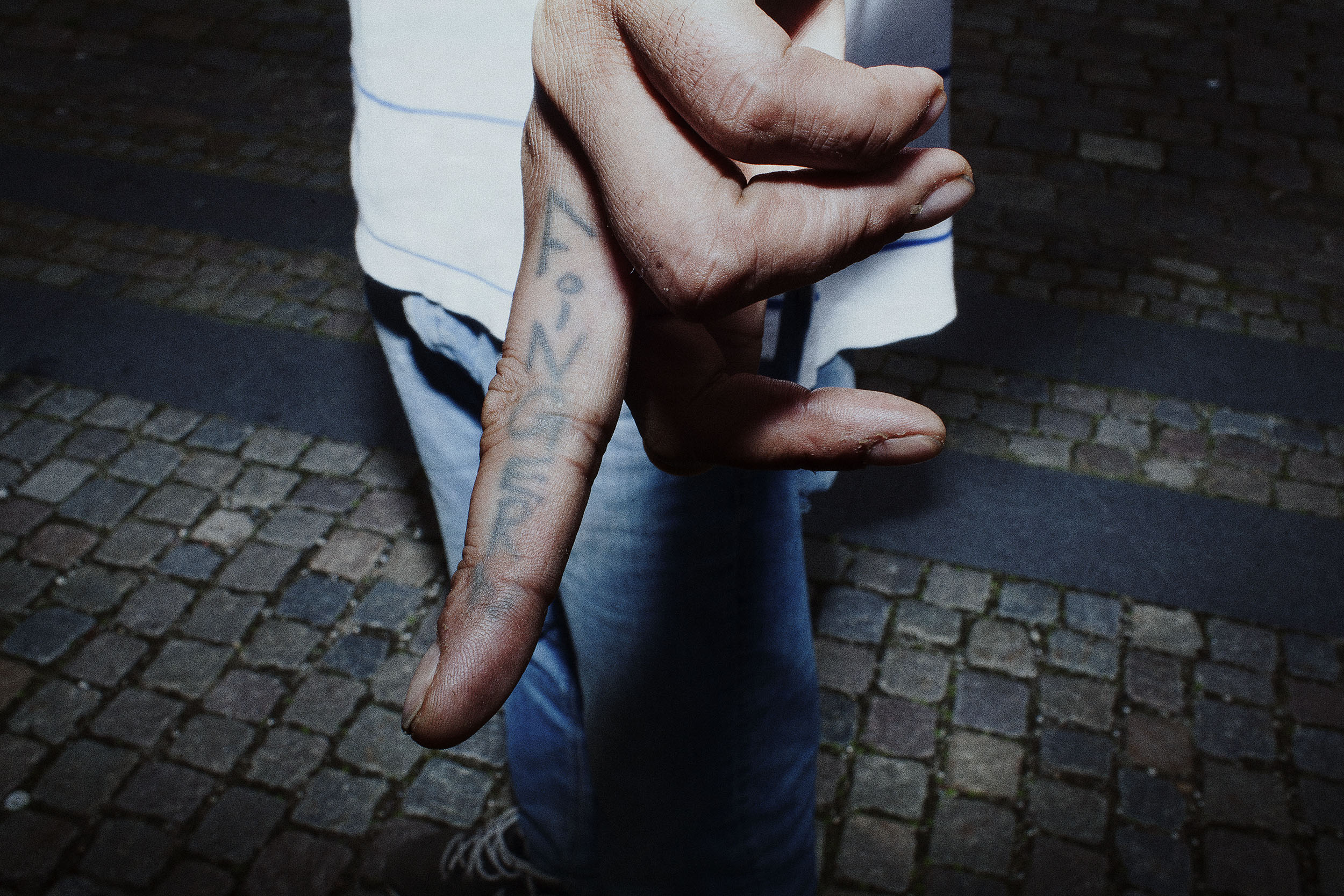

Bob Krintel’s tattooed legs are tanned except for a ring of pale skin around his ankle. It is the only sign of his recent four-month sentence for drug crimes. “When people ask me about it, I just tell them that I wore a pedometer,” Krintel says.

The 37-year-old refers to his life of crime as a “profession” he has worked in since he was 14. All in all, he has spent 11 years in prisons across the country for drug and violence-related crimes. He served his last sentence at home.”

He agrees that hanging out at home sounds like a pretty good deal when the alternative is prison, but that’s been far from his experience. “Wearing a tag isn’t easy,” he says. “It was a difficult time. In many ways, I would have preferred serving it in prison. Inside, I don’t have to listen to my wife complain about me not doing anything and my son wanting me to do stuff that I can’t do. Being in prison is much easier. It’s hardly punishment – you get three meals a day, there’s a sense of community. It’s like a crime syndicate.”

The unannounced visits from probation services and the mandatory urine samples were especially frustrating for someone with a drug addiction. He was forced to deal with his addiction – something, he claims, he never had to do in prison.

“Prison is just a big boys’ club. It’s a game – us against the officers,” Krintel tells me. “I would just smoke myself into a stupor. What were they going to do? Put me prison? I was already there. They can force you into isolation, but after that you just return to your friends in the general population and smoke hash again. All of my urine samples tested positive for THC. It’s all in my file.”

I reached out to the Danish Prison and Probation Service to verify Krintel’s versions of daily life in Danish prison. “These accounts are grotesque and we do not recognise any of the claims made,” said the Head of Security, Lars Bau Brysting, via email.

Brysting went on to refer me to the prison warden in Nyborg, Henrik Marker, who also struggled to recognise the guys’ version of jail time.

“That’s very far from the perception we have of daily life here at the prison,” Marker says. “It sounds to me like the former inmate was under the impression that he had certain liberties in prison and that he could party like he wanted to, but that doesn’t resonate with us here. The staff and the prison officers are in control.” Marker does admit that they are “aware of inmates trying to smuggle in illegal substances”, but says they combat that with routine searches.

Though Krintel, Petersen and Kongsbirk would rather be in a cell than wear a tag, they all admit that serving their sentences with an ankle monitor has helped them plan for a more productive future.

“I haven’t had a job since I was 16, but because I was allowed to serve my sentence outside of prison, I was able to secure work as a farm hand and I’m currently working on setting up my own business,” Krintel says. “I’ve put my old life of crime behind me.”

This article originally appeared on VICE DA.