The Concept of Women ‘Having It All’ Has Never Been Realistic, But Now It’s Extinct

Credit to Author: Emma Garland| Date: Fri, 08 Mar 2019 13:52:04 +0000

It has literally never occurred to me that I could “have it all”. I spent the first 18 years of my life in the Rhondda, where women either drop out of school around their GCSEs, have kids, a marriage and a mortgage – all within a five-mile radius of where they grew up – or, like me, forego all that, move away and become a weirdo the neighbours don’t know how to make small talk with. In the UK, class has an inescapable pull over your life, and – this side of the millennium – unless you were born into prosperity, your options are either: traditional or professional. You can’t have both, at least not without an uphill fight.

The concept of “having it all” is one that specifically applies to women, and began as a sort of motivational phrase kicking back against the notion that women couldn’t possibly be in the workplace, because then who would be at home?

However, the line has never held water – not even for the superhuman, rich or self-employed – even if the sentiment has remained persistent. Ultimately, it boils down to women having the option to have a career and raise children, and be successful at both. But the reality is that this idea excludes “normal” people like me, and those who have it much worse. As a concept, “having it all” has only ever existed within the purview of those comfortable enough to have never faced any real obstacles. Of course, that’s not what we were told while we were growing up.

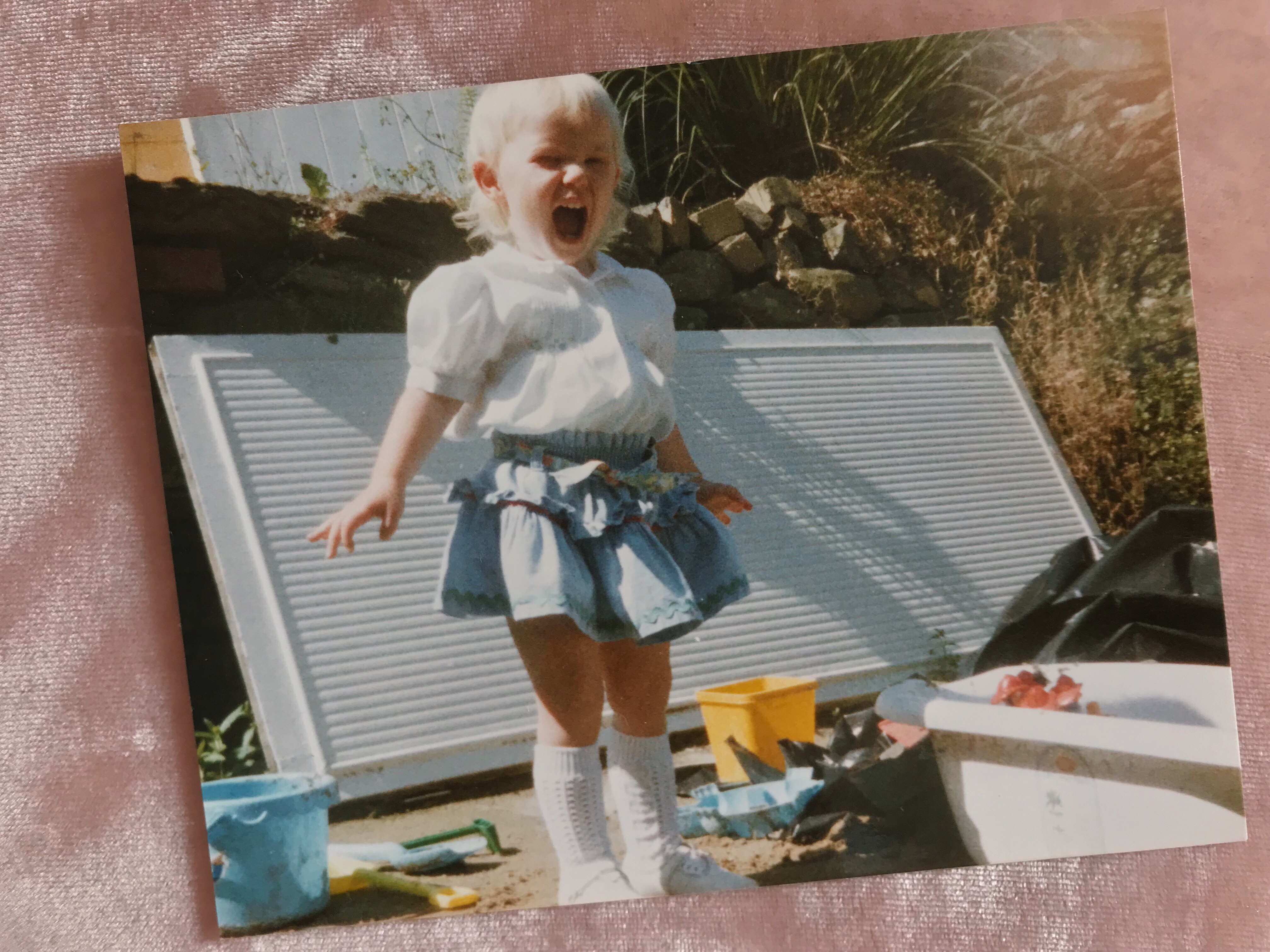

The Rhondda is a deprived area, even by South Wales’ standards. It has a poor life expectancy, poor educational attainment and high rates of unemployment compared to the Welsh average. For the first few years of my life, my parents slept on sofa cushions on the living room floor so I could have the one bedroom in the flat – something I only found out recently. My childhood was amazing; the Rhondda is a beautiful, dogged, ridiculous place to grow up. But everyone reaches a crossroads: you stay, you go. Traditional, professional. This was the way of things – until Tony Blair, who lied and said I could do anything I wanted.

The Blair Years were a wonderful time of hope and ignorance. A time before Facebook and the total collapse of the global financial system. The government was actually investing money in education and ushering us, like pushy parents, towards Russian literature degrees at regional universities, while whispering “every child matters”. Apprenticeships? Skilled work? Manual labour? Not for Blair’s children, thank you! They could do anything they dared to dream (unless they weren’t academically minded or had aspirations in a different direction to higher education)! Despite a 15 percent unemployment rate in my local area at the time, there was a good five-year period in which I genuinely thought I could write novels for a living.

After the financial crisis, the idea of “having it all” went out the window – not just for women, but for everyone. That kind of ideology simply can’t exist when you’ve got multiple generations of skilled workers competing against over-educated graduates for the same part-time jobs in Tesco. I had at least six different employers in the two years after my graduation, and spent the time between them on JSA, with helpless personal advisors suggesting a pivot to forklift driving. The idea of having a “career” was a distant shape, a small possibility, but the idea of having kids was absolutely laughable. If I got knocked up I could make it work, if I really wanted to, as my parents and pretty much everyone else around me did – but I would have to stay put so they could help. I didn’t “choose” a career over children any more than the people at my school “chose” to drop out. This has no bearing on general happiness or fulfilment, of course. We all make choices within circumstance, and it doesn’t matter what you do with your life as long as it’s what you want. “Having it all” is a relative concept, which is why it’s a useless mantra to begin with, but fundamentally Britain has become a country that stacks its odds against you from the start. Even as the economy has recovered somewhat, social mobility has stagnated, working conditions are worse than ever and the housing crisis rages on. Is it any wonder the conception rate for 20 and 30-somethings has fallen over the last few years in England and Wales when young people are forced into cities to find precarious employment and then trapped there by lack of rent control? Who can even conceive of “having it all” when we can’t even paint our own walls unless dad bought the flat as an “investment”?

It seems the national conversation has finally caught up lately, but it’s created a pressure cooker of disillusionment. After decades of government policies that have left entire chunks of the country to drift, while wrecking the planet in the process, with seemingly no end or sense in sight, the future is being framed as an impossible environment in which to raise children. At the same time, the gig economy has led to the unfortunate revival of a strangely 1980s brand of girl-bossery couched in emotional independence and careerism. So on the one hand, we have a generation of mainly middle-class influencers wielding the unattainable over the struggling, reinforcing the idea that the Career You Love is within reaching distance for anyone willing to push themselves hard enough. On the other, we have professional women delaying the births of their children to vote against Brexit and opting out of having kids entirely as a protest against climate change. If this is “you can have it all” then the following line should surely be “my empire of dirt”.

Undoubtedly, the realm of possibility for women is greater now than it’s ever been – even if many of the career prospects have involved pushing for the right to take a man’s place holding up the same structures. But what happens when the realm of possibility for both aspirations – career and children – are diminished? What happens to the scope of our lives when we can’t opt out of work but we can’t opt into parenthood either?

The question now isn’t “can I have it all?”, but “what can I have?” – which has always been the case for society’s less privileged, but years of austerity and inaction are beginning to make it the general default. At this point, some form of personal income is mandatory regardless of gender identity, but starting a family is an option most people can’t afford. If things are to improve, mainstream feminism needs to stop burying its head in unethically produced slogan tees, transphobia and dusty old arguments about whether makeup is oppressive. It needs to break further away from capitalism, not cosy up against it for body heat as we hurtle into the abyss. Now, instead of progressive workplace practices and flexible domestic situations, we have pay pigging as praxis – not out of necessity, but an arse-backwards sense of redistributive justice – and giving up the right to have children in the hope it’ll lead to government action.

I turn 30 in July. I’ve never seriously considered children because I’ve never been in a position to and, to be honest, I’ve never really liked them. But at some point your body starts… doing things. Totally involuntarily, unexpected things. You meet someone new and say “that’s a cool name” and then your brain screams ‘FOR A BABY’. You inspect people you’re on dates with a little closer, thinking, ‘Yes, but are you old enough to want the kids I don’t want right now but might in a few years?’ You look into freezing your eggs, rapidly close all the tabs when see how much it costs, then think about that girl you knew in year 5 who had 70-year-old parents, and feel weird.

Whenever I go home to visit my family, I always see a childhood friend two years my junior ushering her kid into the house she now owns with her husband, eight doors down from the one she was born in. Sometimes I think it would have been easier if I’d done something different, stayed put somewhere it was possible to sink roots into. Sometimes I question whether I was even “bred” to have the constitution for a full-time career in the first place, so often and so desperately do I find myself wishing for the time, the energy and the financial security to stop working and instead stay home all day getting stains out of tops.

No one can “have it all”, and none of us should put the psychological pressure on ourselves to strive for such an unattainable goal, but which parts of the “all” you choose should always be up to you. Even though I know that if rubbing Vanish into armpit stains all day while my disgusting child screams for attention was my reality I’d put my head in the oven, I still want the option.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.