A Journey Into the Radical Art of Brain Injury Survivors

Credit to Author: Joe Zadeh| Date: Thu, 28 Feb 2019 23:00:45 +0000

There are musicians and poets, chess players and chefs. There are the ones who play pool and the ones who talk news; the scrabble crew, the smokers, singers and dancers; the writers, the yoga gang and green fingered gardeners. Carol is the local poet; she likes to tell horoscopes. Aquarius? “Polite, tidy and clean,” says Carol. “Likes to spend money.” There’s the lady who just wants to sit and watch the ducks swim by in the canal outside. And then there’s the art studio, packed with painters, sculptors, drawers, photographers and crafters. You’ll find this thriving little community behind a coded iron gate on a busy road in London. It’s called Headway East London, and everyone here has had a life changing brain injury.

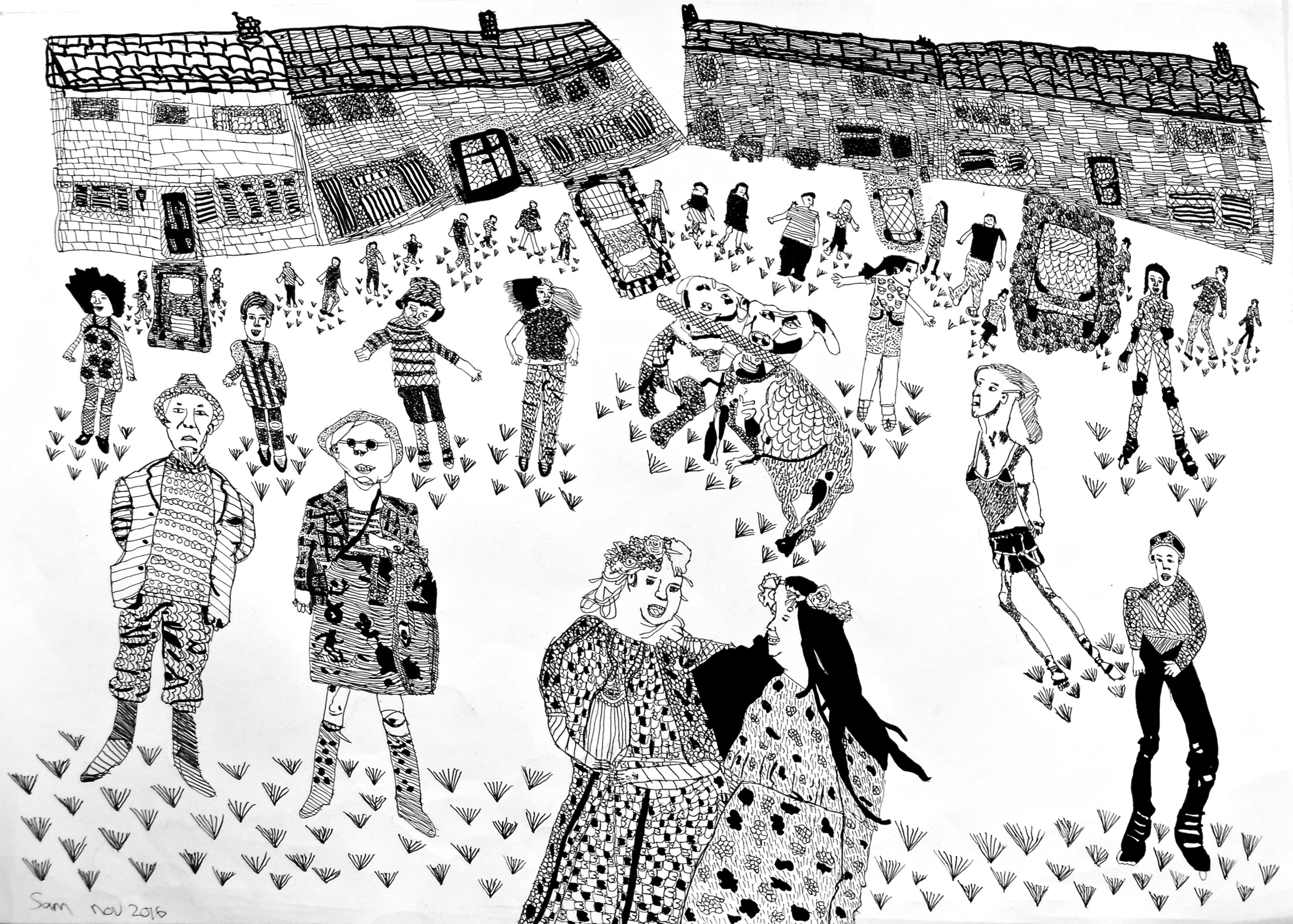

Matthew had a colloid cyst in his third ventricle. Mahmood was attacked by a gang of youths while leaving work. Mike, Trudy, Witman and Billy survived strokes. Brian was hit by a lorry while riding his motorbike. Matthew was hit by a car while crossing the road. Sarah was mugged for her handbag. Lina had a brain haemorrhage in a Burger King bathroom. Danny was beaten up in a nightclub. Sam was in a car crash. So was Nifty.

“The driving energy around here is one of accepting what you can’t change,” staff member Ben Platts Mills tells me in the garden one afternoon. “It’s accepting the loss and chaos that is brought on by brain injury, and then deciding to look into the future with that as your starting point. Alright, nothing makes sense anymore: How can you have a good time? Who do you want to be?”

The art studio opens at 9AM. Members walk in and take up their usual seats; a few are pushed on wheelchairs, some use walking sticks. By 11AM the place is heaving. Sculptures dry in front of fans, giant swollen portfolios of work are stacked high on wooden shelves and pottery piles up on tables. Paintings cover the walls and hang from washing lines, colossal mosaic creatures loom from shadowy corners: in one an elephant, in another a giraffe. The words “DISCOVERY THROUGH ART” are pinned boldly above the paint-splattered sink, plaster models dry beside an electric heater. Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” plays from a speaker in the corner.

Daniel often asks why he is here: “What happened to me? Did I murder someone? Am I on the run?” Usually he’ll sit down and draw in exchange for a cigarette and a cup of tea. Lynda feels a residual happiness after a day in the studio, even if she can’t remember being there. She finds it hard to finish work because she forgets what the idea was when she started. But then sometimes she’ll draw something and it will transport her to a moment from 20 years ago, like a wormhole.

Art isn’t easy for David. His wheelchair must be positioned exactly, paper taped to the table, black marker uncapped and placed in hand. He writes limericks and stories, but mostly he draws animals: a noble boxer dog standing to attention, a lamb sticking its tongue out, horses galloping, trotting or crouching uneasily on lumpy ground. In one, a saddled jockey triumphantly shouts “HA” as he screams past the canvas. David struggles with speech, and conversation is difficult, but if you look at his drawings you can glimpse his personality: his childhood working on a farm, his personal frustration (sometimes he writes “wrong” or “shit agen” across his work), and his rude sense of humour. Many of his animals have a long drooping penis; ask him about it and he’ll say it’s a tail, even when the animal clearly already has one.

Some members paint quietly on easels, others socialise at tables as they draw. On busy mornings you can feel a palpable wave of magnetism that lures you in and makes you silently wonder why you haven’t touched a paint brush since primary school. “A current of energy flows through this place,” says Michelle, who came to volunteer 15 years ago and never left. There’s a silver button on the wall; I’m told if anyone has a seizure I should press it, note the time, and then help to safely escort the other members outside.

Tony wears an old Arsenal football shirt and cap, and usually has his jacket hanging by the hood off the back of his head “so I don’t lose it”. He likes to create huge kaleidoscopic slogans while singing along loudly to Bruce Springsteen. One of his most famous pieces reads “I CAN’T REMEMBER FUCK ALL”, another: “SUBMIT TO LOVE”. They call them Tony’s Bonanzas. The latter was so popular it became the official name of the art studio: Submit to Love Studios. They’re thinking about producing a whole book of Tony’s Bonanzas. One time he went missing for a week and was found sat on a park bench, very sunburned.

Each week, the artists create a range of individual and collaborative pieces. They’ve done group and solo exhibitions at galleries across London (including the Southbank Gallery), they’ll be hosting a workshop at the Barbican Centre in the next few months, and their finished artworks sell for tens of thousands of pounds each year in total. One of their larger collaborations hangs in the London headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland. Almost none of the members had created art beyond their childhood until coming here.

At the back of the studio I find Stephen Staunton, an Irishman in his sixties known by some of his fellow members simply as Staunton (a tongue-in-cheek reference to mononymous greats like Picasso or Caravaggio). He’s deaf and rarely speaks or uses formal signing, instead communicating through gestures and isolated words. He doesn’t like scruffiness; if you have a beard or dirty trainers he’ll give you a damning thumbs down gesture. Since coming here, he’s developed a prolific tendency for vibrant abstract painting. Polygons are his artistic obsession; quadrilaterals, to be precise. He sits down with a pencil, draws elaborate grids across large pieces of paper and then begins to fill each of the resulting quadrilateral shapes with carefully blended acrylic colours.

The staff are starting to wonder if he in fact sees the world in quadrilateral shapes. One time, they gave him an image of a cat for inspiration and he painted three stacked blocks with a rigid tail. Sometimes, when I watch him, I can’t tell if the art making is a liberating experience or a loop he’s trapped in.

The studio isn’t managed by health professionals or art therapists, it’s run by Michelle – a self-trained artist – and her small team of Connie, Alex and Emily. Michelle is short, has bronzy red hair and speaks in a subtle South African accent. She avoids reading the news and describes the way she lives her life as “bantering with the universe”. She’s a stirring motivator and has an infectious energy that makes you want to do whatever she thinks you should do. If you’re in the studio for more than five minutes, she calls you an artist. Members often whisper to me about her, glowingly and respectfully, like parishioners speaking about the village priest. When I ask Michelle about her own art, she tells me she has around 100 pieces of finished work in her studio at home, but nobody has seen them. One day they will, but she doesn’t mind if she’s dead when that happens.

“This studio is about joy,” she beams with a wide smile. “When you come to the studio this is your time to let go, have fun, focus on what you’re doing and not be thinking about your benefits, bills. I like to cultivate love and joy… I know that sounds cheesy, but I do.”

“Why do you think the art studio is so popular?” I ask.

“I think it is an identity. So many people here have lost identity and the studio gives that to them. ‘Discovery through art’ – that’s our studio’s mission statement. What are you discovering? We are discovering what it is to be this new person, and what creativity can do for your life.”

Jason is wearing a maroon “NY” cap and a navy blue Ellesse T-shirt. His walking stick leans against the table and a photo ID card hangs around his neck, in which I can see where part of his skull was removed. “That was taken before I had the implant put in,” he says.

Jason is 44 years old and isn’t that mad about art. His mother tells me he didn’t really paint or draw as a child, and he never goes to exhibitions or consumes great works of art. He grew up in Custom House, east London, left school at 16 and spent most of his life working on building sites with his brother, who’s a stonemason. Jason reckons if he’d said anything about art during the tea break on the building site everyone would have laughed their heads off.

And yet, after my fourth or fifth day of visiting the studio, I can’t stop hearing his name. “You need to meet Jason,” Michelle tells me. “He is a true creative, a true natural. He’s not trying. He has no idea how natural it is to him.”

“He just turned up one day,” says Connie, one of Michelle’s art coordinators. She asked Jason if he was interested in making something and he nonchalantly agreed to give it a try. At first, he just traced his favourite book covers, but Connie soon noticed that he would always have a scrap of paper next to him, where he would test pens by doing small doodles.

“They were such interesting little drawings of faces, really out there stuff,” explains Connie. “I wanted to see if he could do it properly, so I gave him a whole bunch of materials and encouraged him to see what would happen.”

Jason’s headaches began four years ago, and came like a hailstorm. He was on the building site with his brother, mixing cement and shifting stones, when they hit. Everyone thought he was just trying to pull a sicky. He took some painkillers, but they didn’t work. Over the course of the next few days he visited three doctors, who all gave him differing diagnoses and recommendations of paracetamol. Just keep resting, they said.

By Saturday, he couldn’t get out of bed. His mother checked on him: his face was swollen and his eyes were glazed like maraschino cherries. It looked like he’d had a seizure. Jason’s memories after that moment are: being put in an ambulance, signing a form to say he can be operated on if necessary, vomiting into a commode. Then he blacked out. Meanwhile, his mother was informed that the next 24 hours would decide whether he lived or died.

An MRI scan had revealed an abscess in his brain, a pus-filled swelling that can be caused by anything from a heart infection to faulty dental work. They are rare and therefore notoriously misdiagnosed. It would kill him if it burst. When they finally got him onto an operating table he had a stroke. That night he woke up to the sound of his mum saying, “Do you remember me, Jay?” His left arm and hand were paralysed and he couldn’t stand up without falling over. When he went to stroke his hair with his right hand, he realised half his head was missing.

Jason finished his first proper artwork on the 6th of March, 2017. I know this because on every painting he creates he writes “Jason’s” and all the dates he worked on it in large writing. It was a huge and bulbous angry face; vivid and eye-searing, almost viciously bright. In it, the human face is a ramshackle and unearthly device that’s seemingly on the point of explosion, packed with mechanical parts and sections that seem far too complicated to function properly. At the same time, there’s a blissful majesty about it, like something you’d see looking down on you from the sky in the throes of a spiritual hallucinogenic experience. Jason named it “Swollen”. Connie was blown away. There was a style there, from the start.

“What do you think of what you’ve done? Do you like it?” she asked him.

“Yep, it’s alright, pretty good,” replied Jason. “I like doing the art.”

The studio staff continued to supply him with materials and he continued to churn out painting after painting. It came easily, like he was just transferring onto paper visions that were already fully formed in his mind. On the day he finished “Swollen” he instantly began a new piece: another face. It would take him eight days. The patterns were vivid and polychromatic, like something you’d see on an exotic fish in Bahamian waters. This time the head looked to be melting like a candle, from the top down, with its technicolour teeth clamped hard. He called it “Rainbow Man”. “The mouth bit reminds me of when you’re really frustrated and the muscles in your face tense up,” he explained to Connie when she asked. By the end of 2017 he’d completed more than 20 works of art.

While a trained artist might eulogise about their work in terms of “spatial configurations” or “linear elements”, Jason barely wants to talk about his. And he isn’t precious about it either; one afternoon he pushed a half finished painting in my direction and asked if I would like to “have a go on it”. It’s not that he doesn’t want to talk, he loves a chat. Get him talking about films or books, and he’s like a galloping horse. One of his favourites is Catcher in the Rye. He bought it in WHSmith on Oxford Street, read it once, then read it again immediately. No matter what time of year it is – spring, summer, autumn, winter – that book will have an effect you, he tells me.

“But what’s your favourite thing about your art?” I ask.

“Colours, definitely.”

“How do you decide on the colours?”

“Well, I like the reds and all that. But everyone in the studio is using them too, and we all need to share.”

To Connie, this is what’s most fascinating about Jason. “He’s creating very sophisticated stuff,” she says, “but he doesn’t have the spiel to go along with it. I actually went to art college and it was all the spiel and not the quality artwork. And with him it’s the other way around. It’s almost unfair, because they look like pieces that could be a Basquiat. Most artists struggle for years to find an instinctive style and they never quite make it, but Jason’s just got it.”

Jackson Pollock once said, “Painting is self-discovery… Every good artist paints what he is.” In Jason’s work you can see him expressing something he’s not able to put into words about how his mind now works. It’s telling you something about the experience of brain injury in a far more vivid and arresting way than anything he could ever tell a doctor or mutter into my dictaphone.

It took Jason a year of occupational therapy in hospital before he could start moving properly again. He goes to the gym in his local park every few days to exercise his left arm. Art has improved his motor skills, revived his concentration and helped him feel calm. But he still suffers from seizures. When he has them, his whole body goes limp, and it feels like he’s drowning in super glue; like his head is just away from him. His mother can’t look; she has to let his father or brother see to him. One of his paintings, “All Screwed Up”, features a twisted and crinkled figure, barely stood upright in front of a sea of blackness, making the character seem radiant yet totally alone, like a moon hanging in space. “That’s how they feel,” he says.

One afternoon, I find myself talking to Chris, a retired teacher who sustained a brain injury after having a benign tumour removed. He always had an interest in art, but after his injury it turned into a fascination. He has a bag full of things with him that’s almost spilling onto the floor, including books about outsider art, A4 print-outs of a guide to Frida Kahlo he typed up for his fellow members, and a load of flyers for a Submit to Love Studios group exhibition he will be speaking at tomorrow.

“The two most popular exhibitions this year in London have been Frida Kahlo and Basquiat, and neither of them were trained artists,” he tells me. “They are both, in a way, outsider artists. So you can no longer say there is ‘outsider art’ versus ‘proper art’ – they are all the same thing.”

A week earlier, over lunch, Chris had said to me, “You can’t look at contemporary art without acknowledging the art made by the disabled.” It went over my head at the time, but had rattled around my mind ever since. I push him on it and he pulls a book out of his bag and points me to a picture of the German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn.

In 1919, Dr Karl Wilmanns of the Heidelberg University psychiatric hospital, Germany, appointed Hans Prinzhorn as his assistant. He tasked him with building up a collection of art produced by the patients of the hospital. Prinzhorn, a former art history and philosophy student, developed a passion for the project, and by the time he left the hospital in 1921 the collection contained more than 5,000 works by 450 patients. He published his research in his first book, titled The Art of the Mentally Ill.

While the world of science largely scoffed at the book, the avant-garde art world became obsessed. Artist and poet Max Ernst brought the book to Paris in 1922 as a gift for his host, the French poet Paul Éluard. Very soon, a copy ended up in the hands of Andre Breton, the writer, poet and leader of surrealism. The book quickly became a visual bible for the surrealists; to them, this felt like unparalleled access to the pure origins of art.

When the celebrated French artist Jean Dubuffet had the chance to see an exhibition of Prinzhorn’s collection, it changed his entire outlook on the purpose of art. In a letter to Henri Matisse, he described seeing it as “something I have dreamt of for years”. The illness or disability of the artists in question was irrelevant to him; what was remarkable was this idea of an art driven by necessity, created by people with no training, no ulterior purpose, no audience, no museum, no dealers or collectors.

In Britain, the influence of “the untrained” was monumental. On Sunday the 26th of August, 1928, two men arrived in the fishing village of St Ives. One was Christopher “Kit” Wood, a promising and well educated young Liverpudlian just back from Paris, where he mixed with the likes of Picasso and Jean Cocteau. The other was the painter Ben Nicholson, a svengali of British modernism. As they wandered down a back road they noticed an open cottage door through which they could see some paintings. They knocked, entered and found a sea of artworks, hanging askew from the walls, leaning against chairs, stacked on tables and lying on the floor – and in the middle of it all was a little old man with a caterpillar moustache called Alfred Wallis.

Wallis was a 73-year-old retired mariner who had spent 25 years fishing herring, mackerel and pilchard across the Atlantic. But when his wife passed away, he retired and began to paint. He used household paint to create art on whatever he could get his hands on: cardboard, furniture, bits of driftwood, railway timetables, jam jars. The perspective in Wallis’ paintings was radical; the size of subjects would be dictated not by reality but by their personal importance to him. Wood and Nicholson saw in Wallis’ unconventional style a natural inventiveness they yearned for in their own work.

Wallis is now recognised as a major British artist whose work affected an entire generation and shaped the development of British Modernist painting. And yet it didn’t count for much when he was alive: he died alone at the age of 87 in a workhouse. At his funeral in 1942, attendees included Nicholson; the internationally renowned sculptor, Barbara Hepworth; and the Russian avant garde pioneer, Naum Gabo. His tomb was made by the world famous potter, Bernard Leach.

“They took Wallis’ work to London, got him known, and now he’s in the Tate Britain, he’s everywhere,” explains Marc Steene, the director of an art charity called Outside In. “But in this country the only reason Alfred Wallis is loved is because two very middle class artists said he was good. Without that validation and stamp, there is no way we’d know him.”

Steene trained at the Slade School of Fine Art, before working as a volunteer at a day centre in Hove where he discovered the talents of a group of learning-disabled artists whose finished work was usually destroyed and pulped by the staff at the end of each week, so that it could be re-used for papier-mâché. He is sort of a modern art archeologist, desperately trying to unearth creations from beneath the surface of society that haven’t been given the light of day and sometimes don’t want to be found. Steene wants to excavate, protect this art and show us what we can learn from it about who we are.

In his small cosy office on a narrow backstreet in Chichester, West Sussex – opposite Pallant House Gallery, a leading museum for modern British art, where Steene was the executive director – I show him some of Jason’s paintings. “Remarkable,” he says. He has short but sweeping grey hair, dark eyes and speaks in a hushed but forthright manner. As we talk he glides around the office pulling books off shelves and thrusting them into my lap, with declarations of, “You must read this!” and, “You have to see this!” When I tell him I can’t draw, he pleads, “You can! You can draw!” He describes his entire life as a battle to make sure the art world embraces a wider body of artists from a range of different backgrounds.

“We’ve gone stale!” he declares. “The art world doesn’t even relate to people anymore. Most people don’t even engage with it. It’s removed itself from the purpose which it had all our lives. What we see when see people like Jason or Alfred Wallis is art that has a purpose. It hits us directly because it’s honest and has an integrity. But also it shows that art has a deeper function in society for all of us, and we’re just removed from it. Making a mark is an act of self. It’s an assertion of the individual. It is defiant. It’s almost the last thing you can have.”

Currently, Steene has over 2,600 artists on his books, who he is constantly trying to get into gallery spaces and under the noses of collectors. And he tells me he’s barely scratched the surface of what is out there. In his opinion, there are Jasons everywhere, it’s just nobody’s talking about them. Earlier this year he managed to get some of them into Sotheby’s for a seven day exhibition, but too often he faces galleries which instantly see his roster of disabled, isolated or restricted artists as only worthy of their “community programme” and not their main exhibition spaces.

Last week he visited Darlington, where he found a community centre with a group of 70 artists working together. “You could show an exhibition of them and it would stand up anywhere. I could take them to Paris, they were that good,” he says. But in Europe the reception is strange and not necessarily better. When he takes his artists to places like the annual Paris Art Fair, many of the buyers are mostly interested in their mental condition. “Have they been in an institution?” they ask him with a flurry of excitement. “Are they psychotic?”

“In Britain,” says Steene, “part of the idea of the value of art is about the person who makes the work. We are celebrity and personality-obsessed. The thought that someone who has a brain injury might create beautiful art just isn’t widely accepted here. There is a judgment made about the individual at that point. This country has a lot of hierarchical issues and there is a pressure to change, but I think it will be a long time before we see one of the artists we’re talking about having their work in the Tate Modern.”

It’s just after lunch and “Riders On the Storm” by The Doors is rumbling from the speaker in the art studio as I watch Jason work on a set of small paintings: three 10cm x 10cm canvas boards. These, and many other works, will become part of his first ever solo exhibition next month at a small independent gallery in east London. Initially he just wanted the show to be called “Jason’s”, but he was gently encouraged to think of a different name. He saw the word “affirmations” on a piece of paper at home, which he’d been given after therapy. He thought it sounded like a posh, arty word, so he used that. Affirmations.

“Feels strange to have an art exhibition of me own,” he says, as he rifles through colours. “It’s funny to think of myself that way.” His fingers settle on a bright orange – he shakes it with his right hand, passes it to his weaker left, takes the lid off with his right, drops the lid, then passes the whole pen back to his right, and begins making marks, switching from painting to painting with the swift precision of a master chef.

There are about 20 other members in the studio, busy creating. A meditative hum has risen into the air, the unmistakable absence of sound created by a group of people submerged in a state of flow. Quietude; clicking paint pens, squeaking wheelchairs; bits of paper being moved, scratched, painted and manipulated; hands being washed, voices singing in that soft shy way people do when they can’t help but sing along. The smell of the materials; the nostalgic whiff of glue; the unique pleasure of watching something form that didn’t exist before.

It feels like they’ve re-discovered something ancient and precious about creating; an impulse many of us have forgotten or had drummed out of us at school; something we could be losing by letting the tradition of art slip away from our everyday lives and just become something we read about in the news or stare at in rarified galleries. Then the music stops and someone asks if anyone has any requests.

“80s please,” says Jason, and the pounding sound of Dead or Alive’s “You Spin Me Round” fills the room.

Some names have been changed to preserve the anonymity of certain members.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.