Instagram Is a New Frontier In Women’s Life Writing

Credit to Author: freya marshall payne| Date: Thu, 28 Feb 2019 19:03:54 +0000

Digitisation has profoundly changed the way we live our lives. We can share our second-by-second observations and show the world what our faces would look like if we had dog ears, all with a few taps off our screens. Although, in the grand scheme of history, this stuff is still relatively new, social media – especially Instagram, reportedly the fastest-growing network – joins a long history of humans expressing themselves for an audience.

As a person on the internet, you already know Instagram users (especially young women and femme-presenting people) attract a particular type of derision, painted as vain and inauthentic because of their selfies, stories and liberal use of the Huji app. As if I needed to tell you: this is a narrow perspective. Our Instagram feeds document our everyday lives, and updating them seems like a constant process of asking: “Who am I right now?”

It’s a question women have been answering since long before social media, mostly through writing about themselves, documenting their own experiences and memories. This type of “life writing” has always had an especially powerful potential for women. Writing about emotion and the everyday, when even women’s fiction has been historically dismissed as frivolous and domestic, is two things: a subversive way to find wiggle room within the patriarchy, and a radical method of claiming your own worth.

Some time-travelling to look at women’s life writing through the centuries shows us a lot of similarities between what women have been doing for years, and Instagram. If you think about Insta as just the newest medium in a long and rich history of women’s autobiography, it makes sense in a whole new context – one that makes us examine our prejudices about curation and communication in our digital lives.

Early Women’s Autobiography

Before we communicated through phones, people – obviously – wrote letters. They came into fashion among rich men as long ago as the 14th century, but British women were only really able to get on the bandwagon once there was a postal service and literacy was on the rise. By the 16th century, women were taking full advantage of letter-writing.

Curation was also definitely a thing back then. Academics have found that women’s early autobiography borrowed from styles of romance and history writing, which let women narrate their lives with the drama and intrigue they felt they deserved. They also didn’t stop at letters and diaries: women wrote about themselves and to each other through cookbooks, prayer books and even poetry.

For centuries, women have been presenting their best lives and writing about themselves for an audience in a way that made them the main characters in their own stories. You might say, then, that presenting a self to the world has always been more of a way to stake claim to your own power and value than a vain desire to fake perfection.

Nineteenth-Century Women’s Scrapbooks

A bit like social media, scrapbooking was a fairly democratic creative free-for-all. In the 18th and 19th centuries, cutting, pasting and writing comments helped women talk back to power. At the time, women speaking in public were routinely ridiculed, and scrapbooks show how aware women were of their place in the public eye.

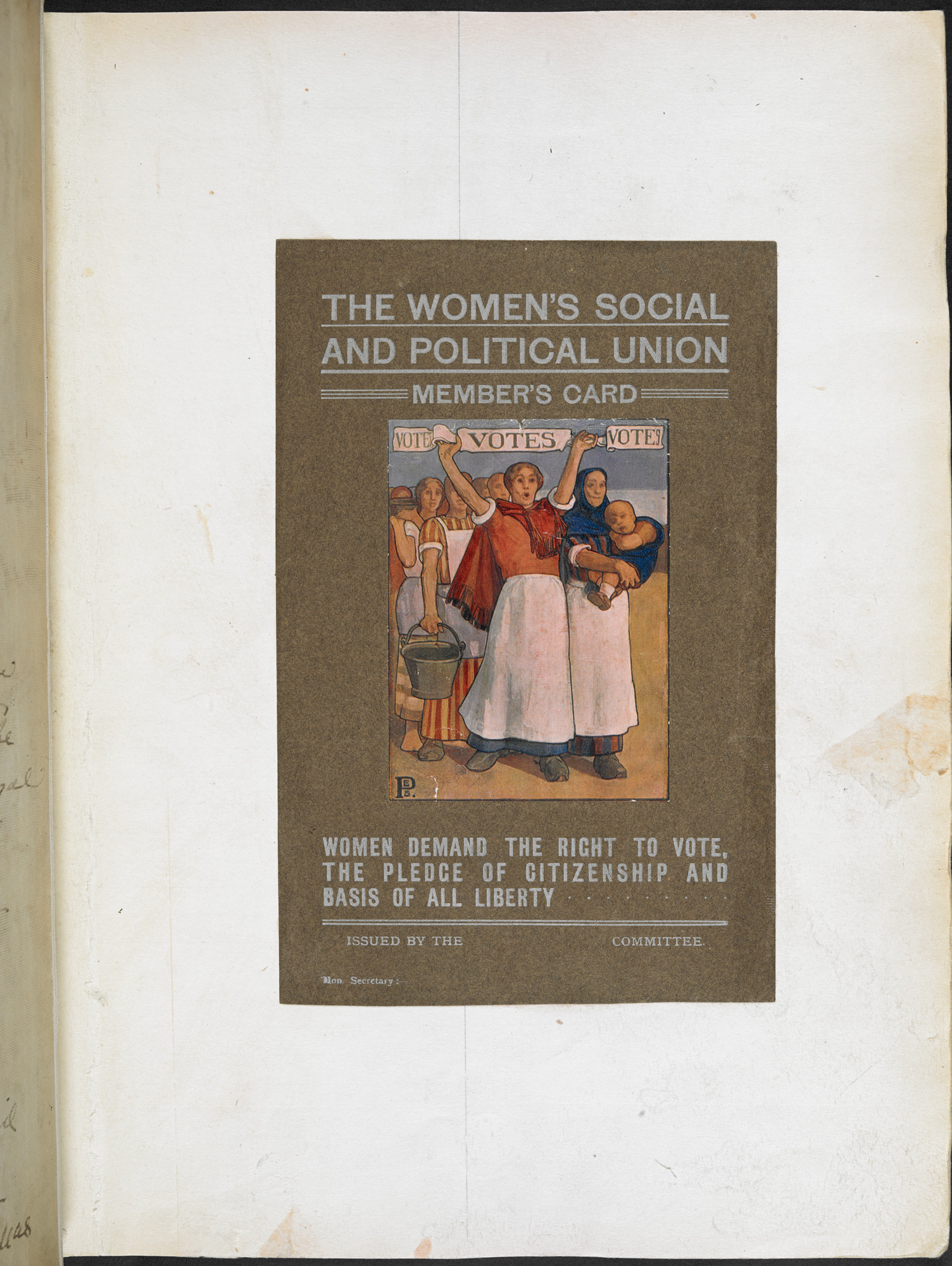

Women’s Suffrage activists in the US and UK are especially notable for scrapbooks which showed their personal memories and thoughts on the actions they were taking, alongside the “official story”, as represented by newspaper clippings and photos. There’s also plenty of hero-worship in the scrapbooks, almost like a proto-version of stan culture: for instance, the American mother and daughter Suffragette duo Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller celebrated abolitionist icon Harriet Tubman with a 1911 photograph.

Writing for an audience and fangirling, therefore, aren’t unique to Instagram: even as far back as before (some) women had the vote, the women winning future rights were using these practices as a way to claim space in the public world.

Modern Women’s DIY Publishing

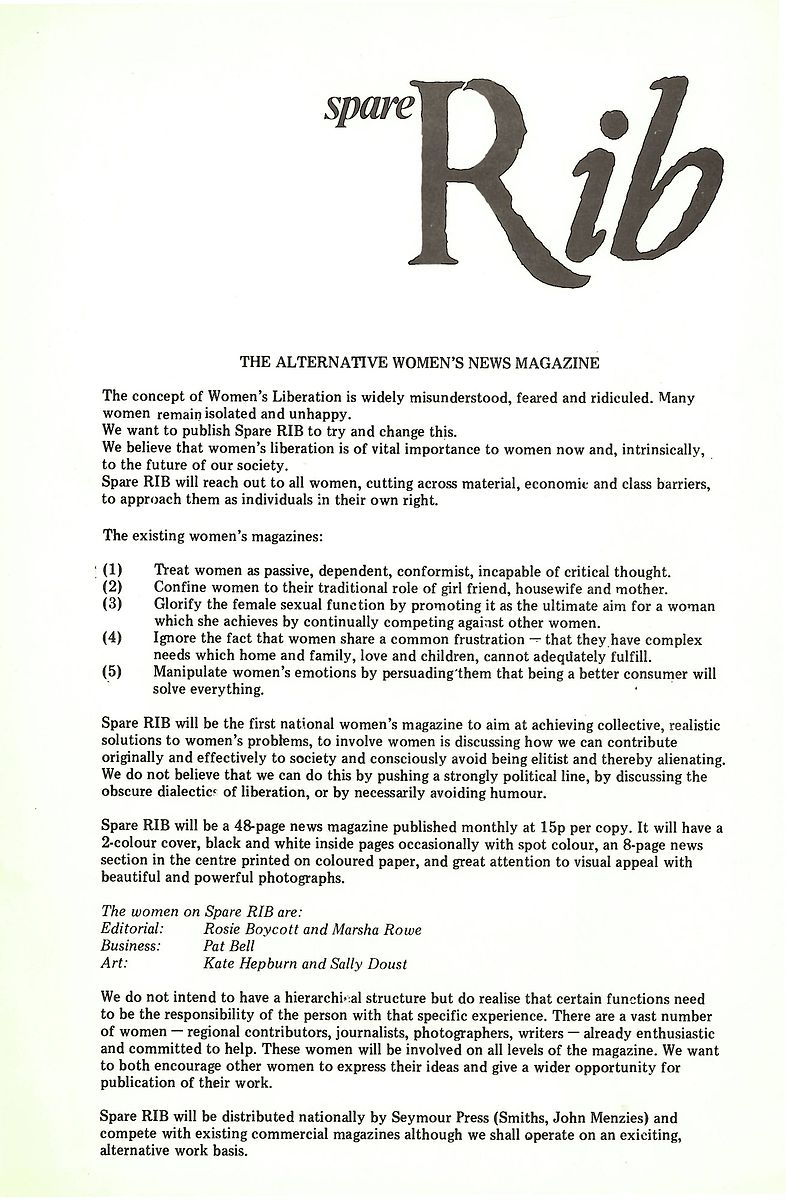

This whole article has been about how “the personal is political”, and that has been a slogan of the feminist movement since the 1960s. It means that personal problems are in fact common results of gender inequality, and the Women’s Liberation Movement started publishing their own media as a central part of their “consciousness-raising” work to share the “personal” and find shared experiences and mount resistance. From the 1970s on, developments in academia and publishing allowed the histories of the women who were only able to write about themselves in diaries and letters to begin to be rescued and re-appraised.

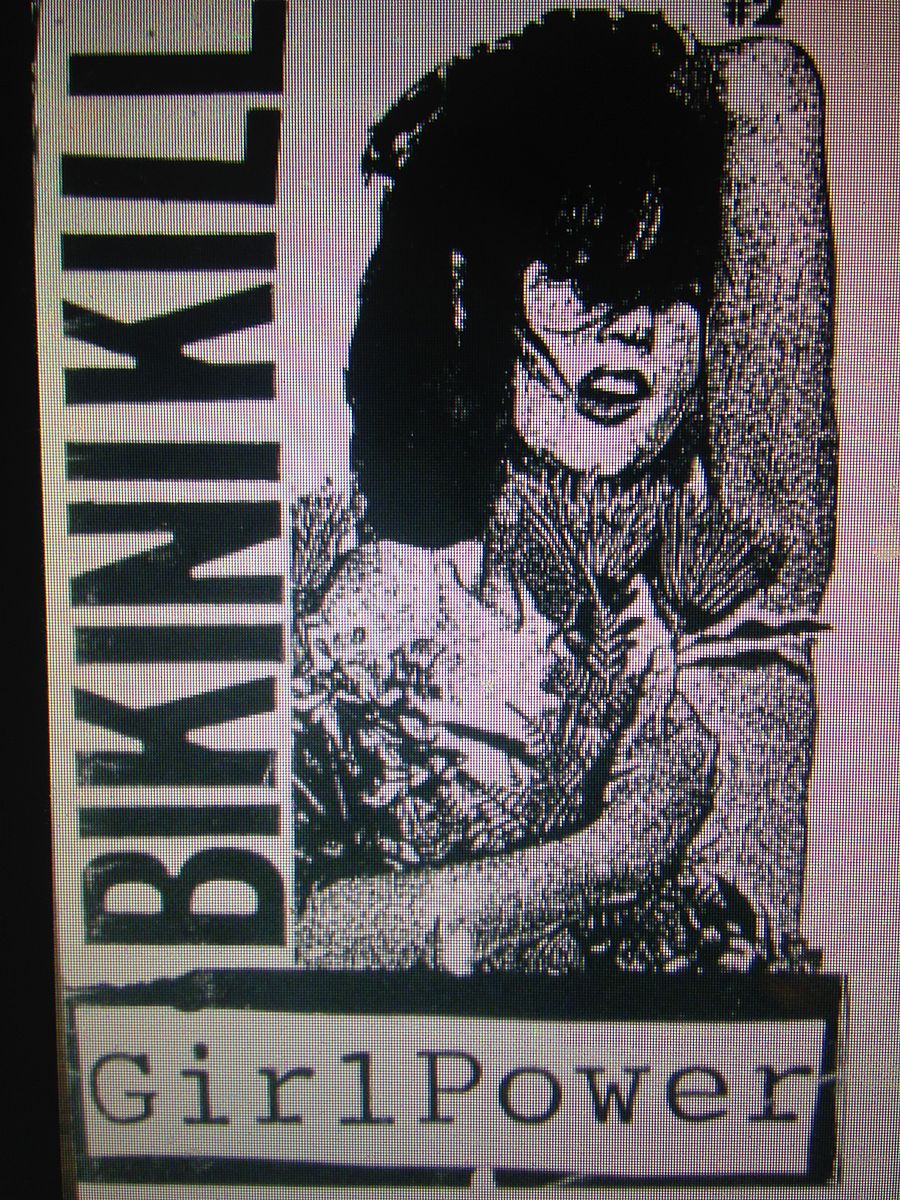

In the 1990s, things only got louder and more assertive when the Riot Grrrl underground feminist movement seized punk’s means of fanzine production and started writing their own stories. They documented the inequalities of the male-dominated punk scene, but they also wrote about and questioned their own DIY feminism and its contradictions.

Riot Grrrl zine-makers were sometimes dismissed for simply being fangirls, but their hero worship was also about solidarity in the face of a punk scene that deified endless identical bands of boys. And, like Instagram, their writings trod the line between private and public as they moved out of gig venues and were posted across the Atlantic.

*

This potted history of women’s life writing shows a few continuities in how women have always shared their thoughts and feelings with the world, and the power behind these strategies. More than that, though, it sheds new light on the easily-held prejudices which say that Instagram is a platform for vanity and fakeness.

Curation has been around a really long time, as have selfies – and women have often used them as strategies to take control of their own stories. And one could argue that while life writing gave many women the ability to stake claim to their own narratives, all of this was – and continues to be – affected by the power structures at work in society to silence people, privileging those who were white and at least middle-class.

Social media, therefore, in all its democracy, feels like a logical conclusion of life writing, whereby everyone can present as they want to be seen.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.