‘Two For Joy’ Isn’t Your Standard ‘Gritty’ Drama

Credit to Author: Oliver Lunn| Date: Mon, 18 Feb 2019 14:49:10 +0000

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.

How do you translate crippling depression – that feeling of being bolted to your bed – into moving pictures and sounds? How do you work grief into a narrative without making it as paralysing as that emotion itself?

British filmmaker Tom Beard knows firsthand how hard it can be to pull yourself out of bed in a certain state of mind; to want to get better, but to be dragged down time and time again. Maybe that’s why, watching his his first feature film, Two for Joy, it feels like one of of those rare instances where a filmmaker has managed to depict what it’s like to experience depression in real time.

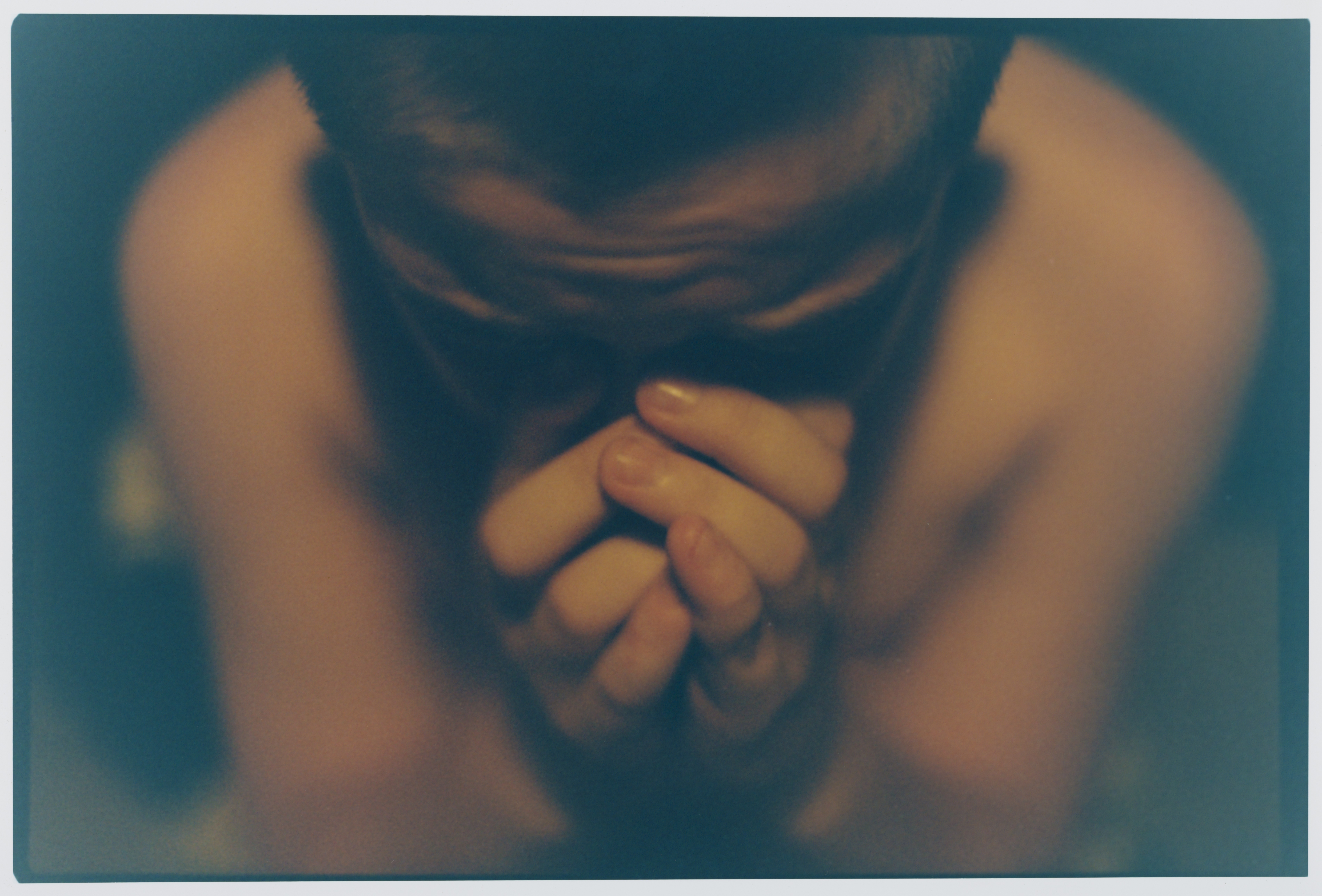

Two For Joy follows Aisha (Samantha Morton), a mother grieving the recent death of her husband. Her two young kids are also grieving – or trying to, but their mum’s mental state barely allows them room to breathe. She’s too lost in her own depression, buried beneath unwashed sheets, all tangled hair and pasty skin. Her daughter, Vi (Emilia Jones), feeling the strain of caring for her mum, suggests a weekend trip to their dad’s old caravan on the coast. Upon arrival, two storms converge as they meet another fractured family with an absent father.

Shot on 35mm film with rounded corner – which gives the feeling of thumbing through a family photo album – Two for Joy is a harrowingly honest portrait of a trauma-stricken family. It weaves together the knotty themes of grief, loss, mental health and class, without banging you over the head with any political agenda. Though Beard hasn’t been through the loss of either of his parents, parts of his movie are clearly rooted in personal experience. The film is shot in the same caravan he used to visit as a kid.

I met the director at a cafe in Shoreditch to talk about the film’s depiction of mental health, how he managed to burrow beneath the surface of his characters, and why he consciously avoided that grimy British social realist aesthetic we’re so used to seeing in independent films.

VICE: Hi Tom. The script feels intensely personal; how did it come about?

Tom Beard: When I was writing the script I was in a bad mental health state – drink, drugs, everything. And then when we sent the first draft of the script out to Sam [Morton] and Billy [Piper, who plays the mother in the other family] and the casting director, they all came back like, “Wow, this is great!” But with that first draft there was no love in it in regards to the characters. It was so raw and visceral. I think it was just painful, especially Samantha’s character. So I came back to the script and I was a bit more empathetic.

With Samantha’s character – the mum – you can see she’s affectionate, that she wants to get better for her kids.

That’s one of the things that was really important to me about the depression and the mis-prescription of pills. There’s still a personality there that’s always coming out, and then you get pulled back in. I had that, and I wanted to portray it. She’s not a bad person, she’s not a bad mum, she’s in the midst of something.

I read that you related most to the mum, that you suffered from bipolar disorder and experienced similar sleep paralysis?

Sleep paralysis, yeah, and waking dreams. The scene with her and Vi at the beginning was almost me and my girlfriend, but twisted into that mother-daughter dynamic. It was like, I can’t get up – just not able to get out of bed. It’s completely paralysing. There’s a moment in the caravan when [Aisha] sits up and pulls the cover off – that’s such a hard thing to do in that state of mind. In that moment she decides that she wants to make a change, but the wheels are already in motion. The kids are already gone and the tragedy is already unfolding. It’s not to do with neglect, it’s to do with these two storms colliding. The kids aren’t able to deal with their own loss, and there’s a selfish quality to the mum’s grief because she’s not letting her kids grieve.

Where did the mis-prescribed pills idea originate?

I was mis-prescribed medication, so that element of the storyline came from a personal place. It was probably through no fault of the NHS, but I was in a very low place when I [sought help], and they were like, “Shit, we’ve gotta give this guy something.” They gave me an upper, basically. But I’m quite manic, so the minute my mood goes into an up, this thing was sending me all… [laughs]

One size doesn’t fit all.

You have to take some responsibility for yourself, but when you’re in those head spaces you’re just thinking: ‘OK, this is gonna fix me, this is what normal people will feel, or this is what it feels to be normal.’

On top of mental health, you also touch on issues in the care system.

I was helping out with a drama group made up of care leavers called The Big House, in Hackney. I was working there doing a few workshops. It’s a really cathartic way for them to deal with some of these things. One of the things about care is they get so isolated, they feel isolated, and you’re suddenly putting them in a group with all these other care leavers who have experienced similar things. Some of them are so guarded, but then they start opening up and they realise they’re making connections with others who have been through similar traumas to them.

Do you think there are false assumptions in the care system?

One of the stigmas and generalisations attached to care is that it’s to do with the parents’ drug and alcohol abuse. But with the vast majority it’s because their parents are actually too sick to care for them. It’s also that they’ve tried to look after their parent, they’ve been a young carer, and then they’re taken away. So not only do they feel like they’ve failed their parents, but their family has been broken apart as well.

Was there something you wanted to expose specifically about mental health and the care system?

I don’t want to be political with my films. It’s just this voyeuristic thing. It’s shining a light on this subject matter rather than being like, “This is my opinion on it.” With my photography work, too, I don’t have an agenda other than trying to bring something that I didn’t know much about to a wider audience.

The seaside setting was personal too, right?

The caravan that we shot in was the one I used to go to when I was about 12. It was my best mate’s and it still belongs to him. We used to go out in the boats and get into trouble. All the kind of stuff that happens in the film, we would do.

There’s a lot of colour and warmth with the backdrop of the coast, which seems totally opposite to most British social realist dramas that are known for their grimy visuals.

I wanted a colour palette that felt like a bruise. It starts off very blue and purple, and then when they get to the seaside suddenly it’s all these yellows and it’s kind of bright as the bruise is dispersing and healing. That was the colour arch that I was going for, together with [cinematographer] Tim Sidell. I didn’t want to make a dreary kind of social realist drama. It starts in a bad place, but it’s a hopeful film – and though terrible things happen along the way, there’s a lot of happiness in it.

Thanks, Tom.

Two For Joy will be a having a special Q&A screening at Screen on the Green on February 20. You can get tickets for that here, or pre-order the film on iTunes.

All images courtesy of Strike Media.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.