These Photographers Make Surprisingly Fresh Photos of Flowers

Credit to Author: Jon Feinstein| Date: Thu, 14 Feb 2019 16:54:26 +0000

Art history can’t escape flowers. They’re beautiful, loaded with symbolism, and go as far back as Ancient Egypt as one of art’s most frequent muses.

Nearly every major art movement has found its own way to honor and reinterpret them, and unsurprisingly, they’ve had similar popularity in photo history, starting with Anna Atkins’s cyanotypes and Cromer’s circa 1845 Amateur daguerreotype of flowers, and extending through Karl Blosfeldt, Imogen Cunningham, and countless others.

With a subject that could appear steeped in cliché or already done in every way possible, this muse, somehow, isn’t totally dead. The following seven photographers reimagine the potentially tired genre with new grit and energy. For some, like Joaquin Trujillo, Melissa Eder, and Georgia Matsamaki, flowers are the central subject, while for others, like Alanna Airitam, flowers act as an occasional yet important object to help give clues to larger ideas and histories. Still others, like Abelardo Morell and Gregory Eddi Jones, create elaborate floral remixes.

Read on, and make sure to keep up with them all on Instagram.

Abelardo Morell

Abelardo’s Flowers for Lisa turns a romantic gesture on its head. The series began in 2014 when Morell struggled to come up with a gift to show his love for his wife, Lisa, on her birthday. How could he capture the sentiment of a tired gesture—giving flowers—with earnest originality and permanence? Instead of giving Lisa a bouquet that might be forgotten or die, Morell made a photograph. Initially intended to be a one-off, Flowers for Lisa #1 was a simple yet wildly colorful image of flowers in a vase. The petals were strewn about—multiple exposures suggesting their life cycle and vulnerability.

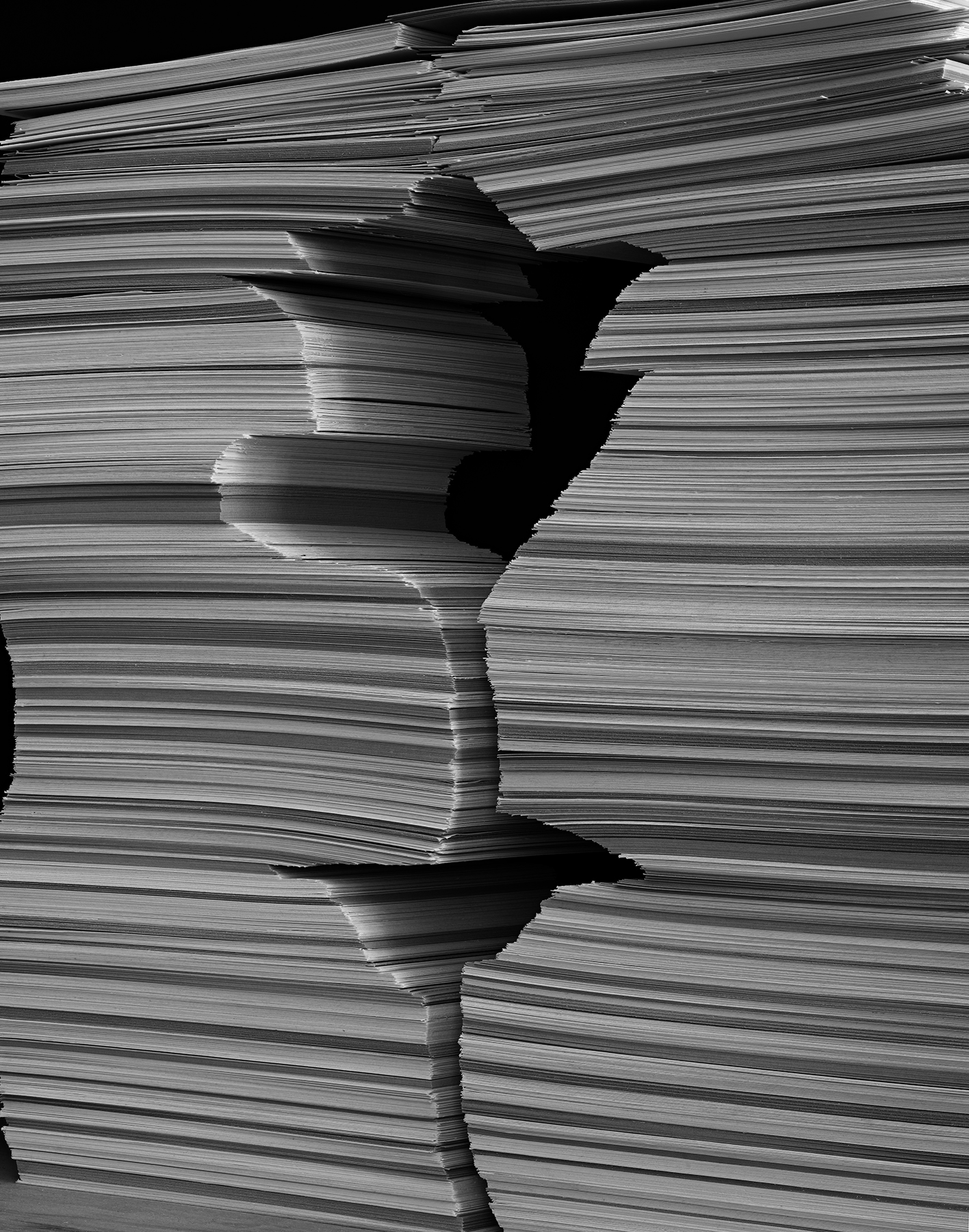

Morell made a similar picture the following year, and in 2016 expanded it into a widely varied body of work that experiments with unconventional arrangements and riffs on the previous photograph in the series as well as images of flowers throughout art history. In one photo, torn pictures of flowers collage together like a visual mood board; in others, formal, double-exposed sunflowers reference Van Gogh. There’s also monochromatic homages to Anna Atkins, and even two stacks of paper arranged so that the negative space between them resembles a single rose. Whether you catch the art-historical reference or not, Morell’s creative versatility make these images accessible to all, and his love and dedication for Lisa pulses throughout.

“I loved working on this subject especially because it has so much baggage,” says Morell. “The reality is that a great number of artists have dealt with picturing flowers in the most beautiful and inventive of ways. Every artist deals with how to represent a thing, newly, with his own imprint but with a nod to what came before them.”

Gregory Eddi Jones

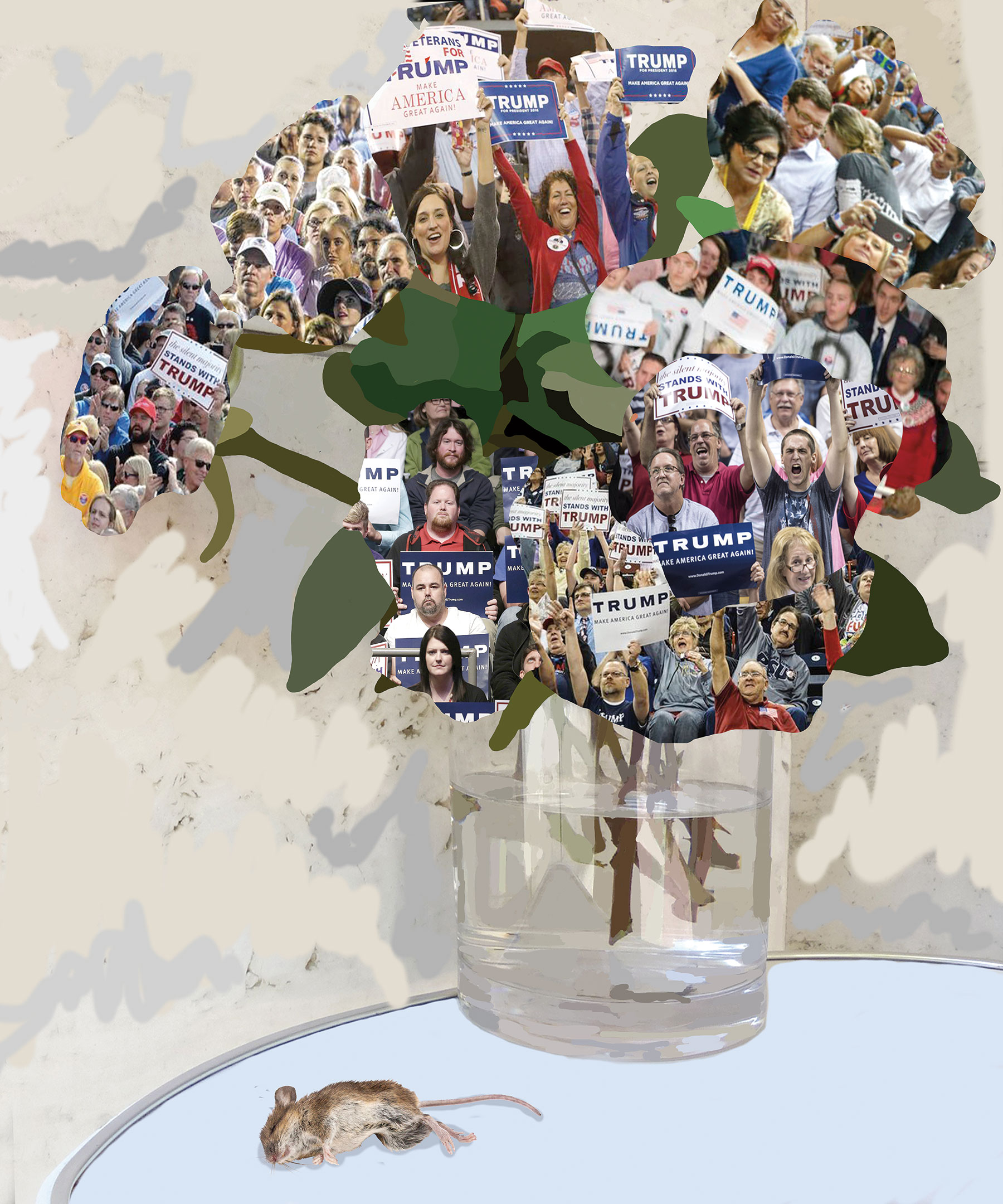

In late 2016, as anxiety mounted toward Donald Trump’s impending presidency, Gregory Eddi Jones began ripping stock images and screengrabs from various news sites, stitching them into elaborate digital collages that resemble still lifes of flowers. In some images, low-res photos from Trump rallies serve as blurry backdrops. In others, photos of Trump fans, campaign banners that read “Trump For America,” emojis, and various forms of digital noise serve as petals and other parts of the floral structure, vying for our eyes and attention. The series and now book, Flowers for donald and Countries Glorious, is a weird, chaotic, colorful mess of information wrapped around a single metaphor: Jones’s parallel of Trump’s popular acceptance and normalization to the classic novel Flowers for Algernon.

Published in 1958, the novel centered on the story of an intellectually challenged man undergoing surgery to triple his IQ, only to see it revert back to his original condition by the end of the book. On the surface, this might seem like Jones could be making a problematic equivalency of Trump’s potential mental illness to the character in the book. However, it’s actually the relationship to the story’s arc of acceptance and regression that Jones is after. “I’m speaking about the sentiments of many Donald Trump voters who feel they’ve been left with little social influence,” says Jones, “and my own prediction that their sense of marginalization will ultimately return when he fails to implement meaningful policies that improve their lives.”

Beyond this initial metaphor, Jones looks at flowers as a historical device, drawing on their power in political protest, and role in providing beauty and optimism in turbulent times. Think of Flower Power, the classic 1967 photo by Bernie Boston of a protester placing a flower in the barrel of a gun. Like Abelardo Morell’s work, there’s also a connection to art history, specifically the use of collage as a form of political protest by DADA artists in the early 20th century. “I realized a few months into the work that the creative problems I was trying to solve had some sense of precedent in the European Dadaism between the world wars, when artists like Hannah Hoch, Raoul Hausmann, and later on, John Heartfield were using collage and irrational aesthetics to reflect the destabilization of European politics.” Jones’s process of digitally cutting up and recasting found imagery—flowers or not—could be considered a revival of the radical spirit of these artists responding to their uncertain times, a counteraction of beauty, or a calming salve to get us through it all.

Melissa Eder

Melissa Eder’s Can You Dig It is a series of floral arrangements made from fake flowers photographed in front of bright psychedelic backdrops. Eder, who grew up in suburban New Jersey in the 1970s and now lives in New York City’s East Village, was inspired by their garish beauty. Displayed in nearly every home and window, they surrounded her. They were part of the culture: loud, plastic, kitsch trophies that could live forever. As photographs, they question the line between shabby “low art” and what’s considered to be a “well-crafted” photograph.

Her process, after scouring the aisles of various 99-cent stores (her favourite is Dollar Power), is as low fi and no-frills as the fake flowers she shoots. She uses a point-and-shoot digital camera and basic lighting, with little to no post production. Her hyper-saturated colours come through careful placement of flowers and polyester spandex backdrops from stores like Spandex House in the city’s Garment District. “I pick a group of flowers and decide which colour I’d like to explore,” says Eder. “Each arrangement explores a different colour.”

Eder’s careful pairing of flowers-to-backdrops is jarring, twitchy, even pleasantly nauseating: a tripped-out neon camouflage that not only creates visceral confusion but toes the line between wha’’s fabricated and what’s real—even when everything in her photographs is man-made. “I’ve often said that when you see the flowers in ‘real life,'” Eder says, “they look pretty crappy. But when they are photographed they are transformed. This will sound weird, but I can almost hear the flowers say, “You want yellow… I’ll give you yellow!”

Eder’s process is a balance between representing something that is aesthetically pleasing, yet also conceptually challenging and digs below the surface. And her title responds to that feeling, alluding to funk music as a major influence and inspiration. “Asking someone ‘Can you dig it?'” says Eder, “is like asking someone if they can relate to you. Can they understand you?”

Alanna Airitam

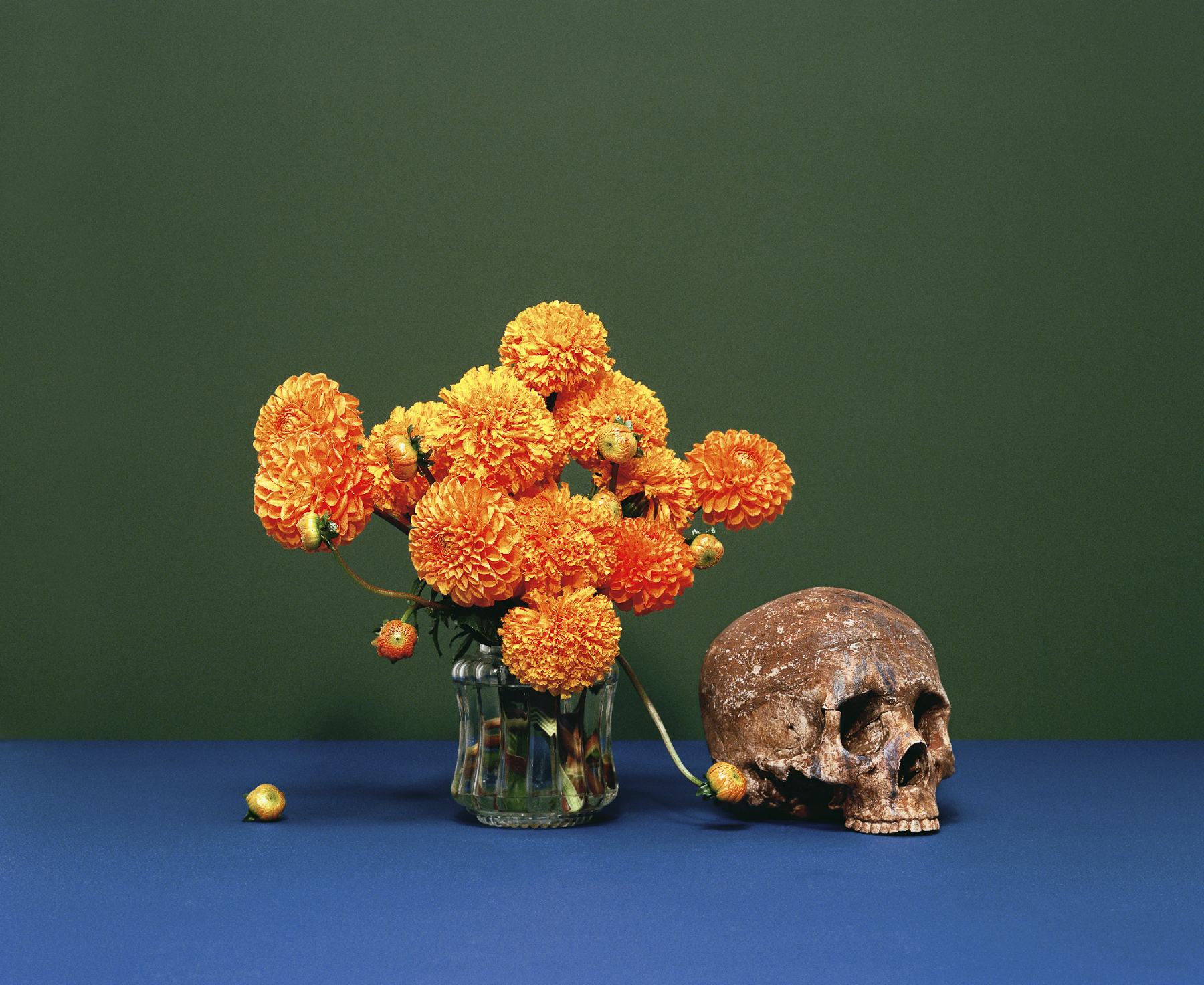

While they’re not present in every image, flowers play a significant role in Alanna Airitam’s series, The Golden Age, which reimagines Eurocentric 17th-century Dutch Renaissance paintings as photographs of historically excluded African American men and women. They have a similar symbolism as fruit and other objects in classic Dutch still life and portraits, which Airitam has her subjects wear or hold as “offerings.”

In one image, titled Queen Mary, 2017—the first she photographed for the series—her subject, a young black woman with a nose ring, stares directly into the camera, and one outstretched hand offers a bushel of grapes, while the other raised palm out, holds a mysterious skeleton key. She wears an elaborate arrangement of flowers around her neck, exuding confidence and coded mystery. “Some of the narratives I work with can feel heavy and adding flowers balances it with some levity and grace,” Airitam says. “And in this crazy world, it’s just nice to have a simple flower to look at every once in a while.”

Like in Melissa Eder’s Can You Dig It, all of the flowers in Airitam’s series are fake, yet her refined sense of lighting, replicating the paintings she’s referencing, makes it hard to tell. “I use a lot of peonies because they are my favourite and photograph beautifully,” she says. “I probably got most of them at Michael’s or ordered online.” Unlike real flowers, these can be used and reused in multiple shoots and are easier to manipulate.

The use of fake flowers might be a subtle nod to Dutch Renaissance paintings of floral arrangements, which were often grossly inaccurate because flowers would die before an artist could properly paint them. Like Eder, Airitam sees a relationship between their plastic fabrication and the tension that exists in believing what’s presented as real in historical and contemporary pop cultural narratives. “It brought up all sorts of thoughts around how easy it is for the brain to justify what we believe,” says Airitam. “This is fascinating to me when I think about a lot of the work I do is about questioning stereotypes and programming.”

Georgia Matsamaki

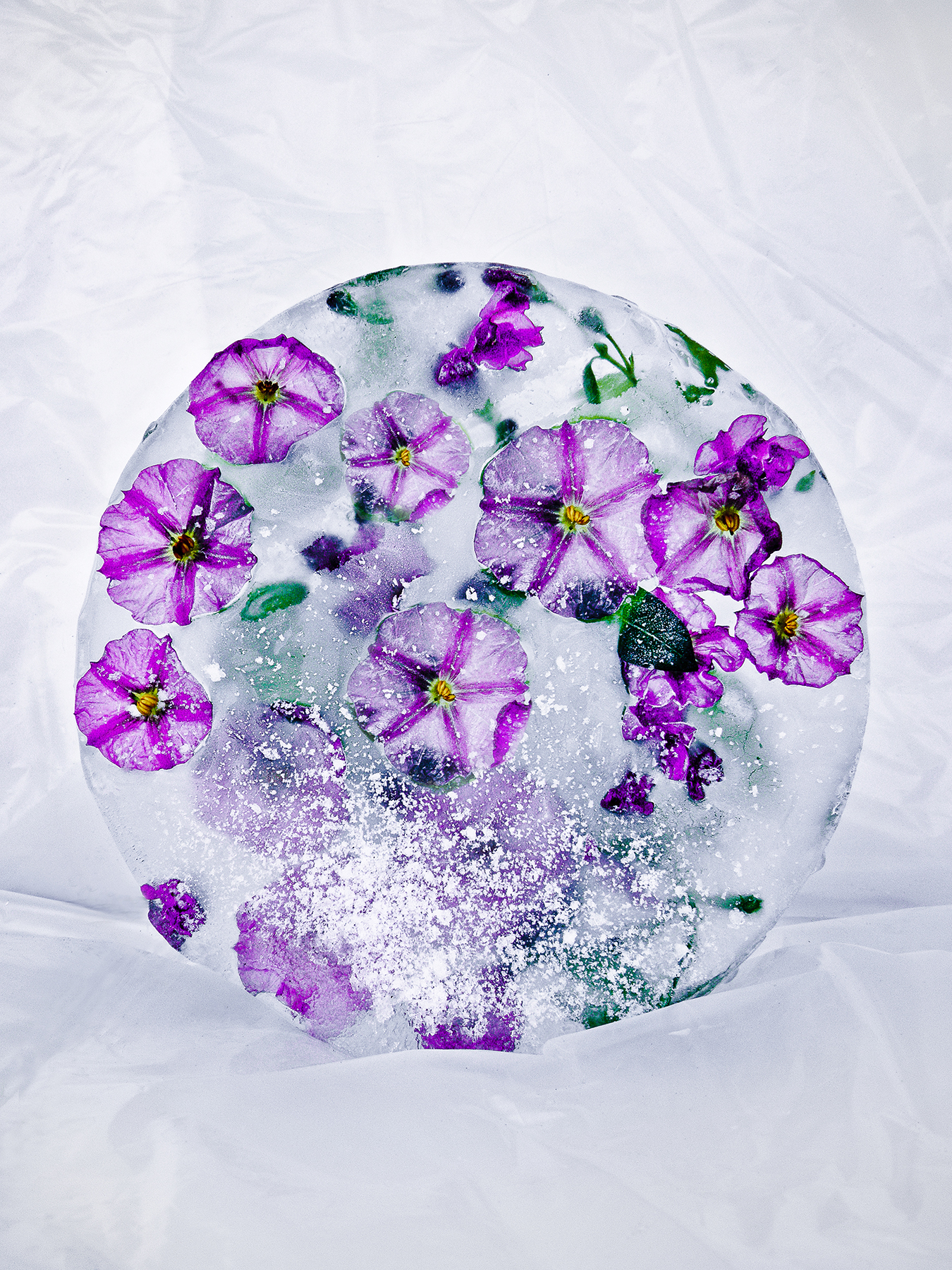

The world in the wake of nonstop digital and social media interaction can be a cold place. Transactions and self-worth limited to likes and Instagram comments can feel stifling. Like photographing flowers, that’s not a new or radical observation, but it’s a feeling that permeates around the world. A few years ago, in response to stilted communication and romantic gestures in her own life and at large, Georgia Matsamaki began freezing different kinds of flowers and photographing them. Working with local florists, she selected flowers that were about to die, catching them in their final moments.

Working within a typological framework, the structure of each photo in her series Freezing Cold is identical, almost scientific. Like Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photos of water towers or Rineke Dijkstra’s beach portraits, our eyes are drawn to their immediate differences. Color, obviously, but also the way petals, stamens, and other details hang suspended. In each image, they push to the edge of the ice as if trying to break free—perhaps accentuating Matsamaki’s feelings of emotional freeze or restriction.

Matsamaki parallels this technologically driven stuntedness to behaviors in Victorian England, and the United States during the 19th century. During these periods, because of socially conservative attitudes toward outward romantic expression, flowers and floral arrangements were often used to send coded messages of love. While the work is hardly a response to today’s increased political conservatism, its commentary on restrained connection rings true.

The specific breeds of flowers aren’t important to each photograph’s symbolism. “Any kind of flower could imply this distant, inaccessible and cold situation,” Matsamaki says. Beyond their ties to romance, for Matsamaki, all flowers, regardless of specific breed or origin, are timeless emblems that, while sometimes cliché, have an uncomplicated sense of freedom. Freezing them as they are about to die resembles what she sees as a general cooling of kindness amidst an “odd communication gap between people of this era.”

“I’m drawn by their plasticity,” she adds, “They are gifted with the precious virtue of stoicism, enjoying the great privilege of sunbathing and dancing gracefully with the wind. Isn’t this uncomplicated freedom fascinating?”

Roxana Azar

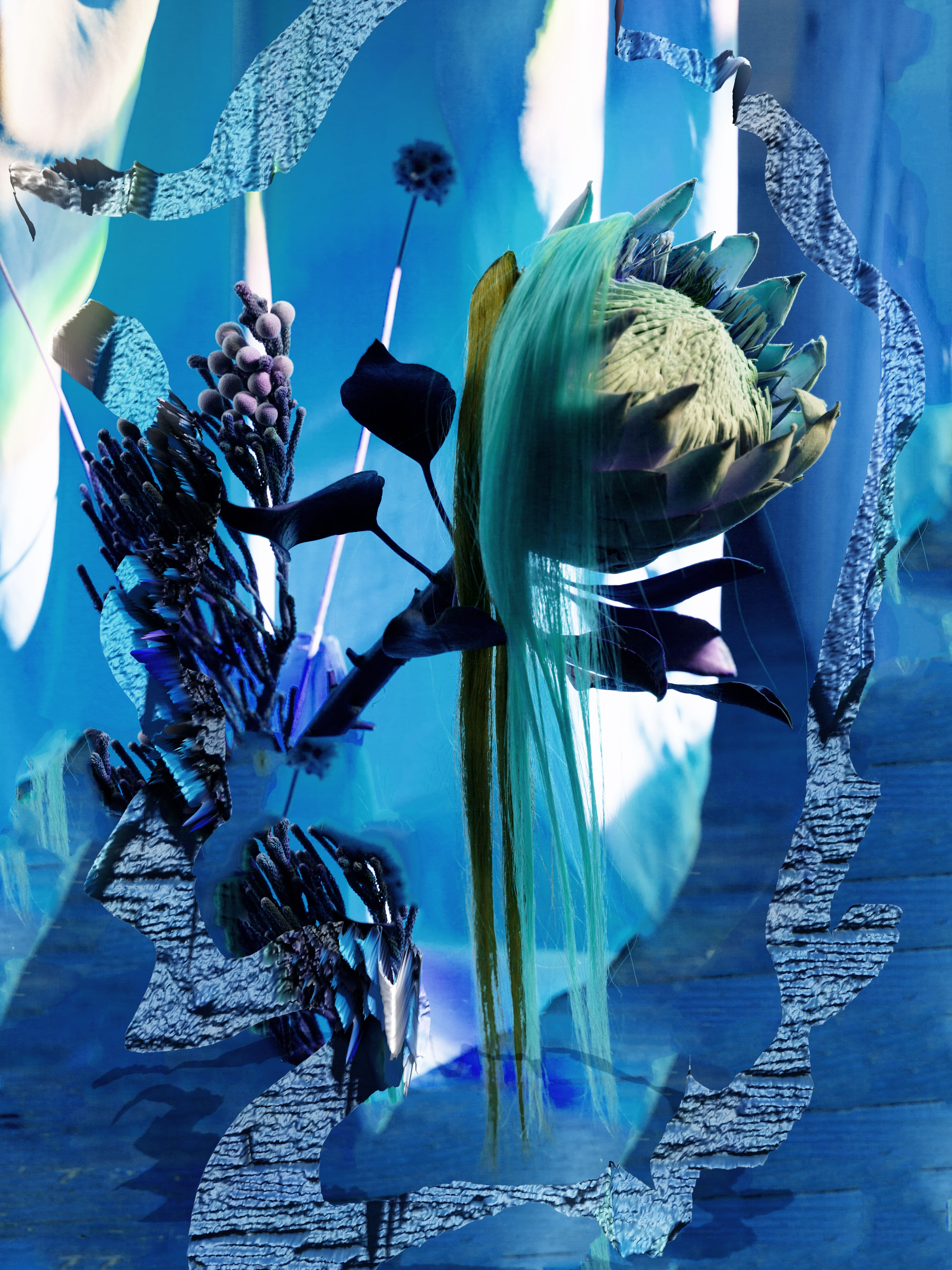

In the 2018 sci-fi flop Annihilation, Natalie Portman and a crew of military scientists enter “Area X,” a mass of swampy wilderness that’s been overtaken by a strange force called “The Shimmer.” It’s hijacked DNA, resulting in strange species hybrids doused in soapy, sometimes holographic effects. If the crew had included a floral still-life photographer, it would have been Roxana Azar.

In 2015, while making photographs “about a vaguely extraterrestrial sentient landscape,” a professor prompted Roxana Azar to create plant life from another planet. In response, Azar combined real plants with random objects from around the house, craft materials and beauty products that resulted in crude, discordant sculptures. This turned into a series of visually confusing photos that at times feel like subversive interventions on a marriage between 90s beauty still lifes and scenes from Earth Girls Are Easy.

In one image, titled Hypnotizing, red Laceleaf flowers protrude from a seltzer-bottle-turned-vase while red splotches splash about the frame. At some angles, they look like paint but a close look reveals them as repetitions of Photoshop’s clone stamp: digital garbage turned delight. Fake rhinestones bedazzle it all, leaving us as viewers saying simply “whoa, wtf?” This image, like many others in Azar’s series, is a carefully constructed mess of shapes, colour, and playful experimentation—equally grotesque as it is beautiful.

In another image, titled Sensing, Azar sticks fake eyelashes over pink lily petals making it look as if they’re closing their nonexistent eyes, batting at our disbelief. While this work could be seen as a nod to “alternative facts,” it’s more about sci-fi absurdity and Azar’s B-movie inspired quest to create an extreme, altered reality. “In a few movies, I’ve watched I noticed the depictions of nature in the future are either distorted, hyperreal, or distant,” Azar says. “I wanted to make these arrangements that had elements of that. I had a few fake scientific facts I wrote about them but they were more prompts for me to create an image.”

Joaquin Trujillo

When he was 12, Joaquin Trujillo left his home in a small town on the outskirts of Zacestaras, Mexico, to live with his brothers in a one-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles, the city where he was born. In the time before leaving, and on his frequent returns, one constant was the importance of flowers in his mothers and sisters homes, which they displayed year round on their patios and throughout their houses.

“They all have their favourite colour, aroma, shape, and name,” Trujillo says. His ongoing series Flores is an homage to the women in his family, their adoration for flowers, and the role they had in shaping his identity. “My arrangements represent what I have consciously and unconsciously obtained from them, Trujillo writes, “as well as what had made me the man I am today.”

Like many of the photographers’ work in this feature, Flores is a serialized study. Trujillo photographs each bouquet from a nearly identical distance against a clean colorful background, guiding viewers to focus on the flowers’ differences in colour, arrangement, shape, and other physical qualities. He sees this way of seeing as having more literally “scientific” roots than you might expect. “In school, my science teacher taught art. Everything was really mathematical, and I think this is reflected in my archival and traditional photographic process.”

In some cases, the flowers have deeper metaphoric qualities. For example, an early photograph in the series was made as one of Trujillo’s sisters was ill. Photographed in front of a plasticy teal green background—a colour that this sister loved—one of the flowers in an otherwise healthy-looking bouquet hangs halfway down, limp, nearly dead. Luckily, “like plants, with water and love,” Trujillo says, “she is much better now.” Beyond the clear metaphor for his sister illness, it’s a reminder of life’s ability to balance sadness with colourful, electric energy.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Jon Feinstein on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.