The Deadly Worst Case Scenario for America’s Xanax Obsession

Credit to Author: Maia Szalavitz| Date: Wed, 13 Feb 2019 12:16:56 +0000

High Wire is Maia Szalavitz’s reported opinion column on drugs and drug policy.

Prescriptions go up. Overdoses skyrocket. People start to freak out. In response, government officials and physicians clamp down on the medical supply of the drug in question. But that seems to only make things worse: An illegal substance—many times more powerful than those commonly given to patients—hits the streets as the death toll stubbornly continues to climb.

If this sounds like the story of the American opioid crisis, culminating in recent years with the proliferation of super-deadly fentanyl, that’s because it is. But it’s also the story of the Scottish response to an eerily similar problem with the anti-anxiety medications known as benzodiazepines (a.k.a. benzos), which include Xanax (alprazolam), Valium (diazepam) and Ativan (lorazepam), among others.

Americans like benzos, too.

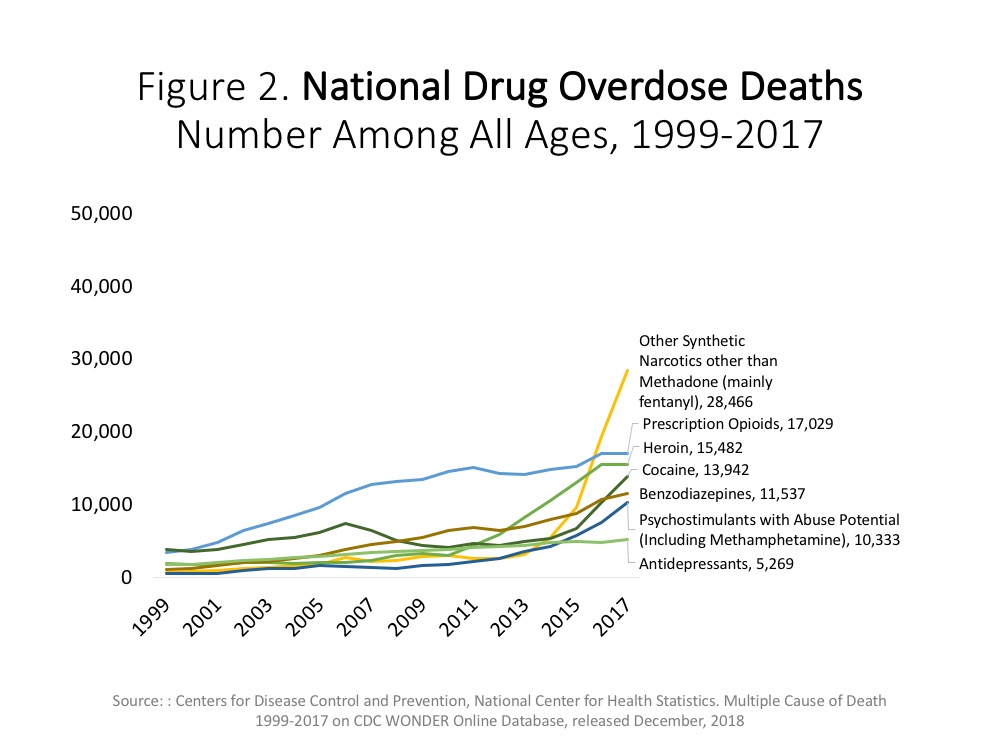

A recent study published in JAMA Network Open found that the number of regular American doctor visits resulting in a benzodiazepine prescription doubled between 2003 and 2015. Meanwhile, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has highlighted that more than 30 percent of opioid overdose deaths involve mixing opioids with benzos, and US overdoses associated with benzodiazepines—the vast majority of which also involve an opioid—grew by a factor of about ten between 1999 and 2017.

These are serious problems in the context of a larger opioid epidemic that has won plenty of attention from politicians across the country. But as glaring stats like these raise the alarm—and they have, with some American patients already reporting that prescribing is being cut significantly—it’s important to look to Scotland for what not to do.

In less than a year between 2017 and 2018, overdose death rates in Glasgow increased by an estimated 43 percent—and another Scottish city, Dundee, cemented its reputation as the “drug death capital of Europe,” driven in part by a flood of strong, cheap, street benzodiazepines.

That surge didn’t come out of nowhere.

“Prescribing has been down for the past few years, largely because there was concern about benzodiazepine misuse within Scotland,” explained Andrew McAuley, senior research fellow at Glasgow Caledonian University. “There was a lot of overprescribing and people were diverting prescriptions to the street.”

McAuley painted a picture of a strong response that mimicked America’s opioid crisis: Scottish government officials created new guidelines for doctors, in an attempt to cut the medical supply. Local health authorities and other groups also pressed various measures to crack down, which had the intended effect in terms of reducing benzo prescription numbers.

But just as with America’s opioid crisis, these supply-side policies seem to have had the opposite effect on overdose rates. People who once had access to drugs that were of known dosage and purity suddenly did not. Drug dealers stepped in to meet the demand, and the global supply chain of illegally-manufactured pharmaceuticals provided the products users wanted.

Which isn’t exactly shocking: Some 80 percent of people who use benzos recreationally combine them with other substances—and benzodiazepines are rarely their only or even their primary drug of choice. “Virtually all are using other drugs,” McAuley said of benzo users. He added that a typical cocktail of substances includes heroin and alcohol, with cocaine increasingly being added to the mix over the last few years.

After the crackdown began, McAuley suggested, it was only a matter of time before people got creative on the street.

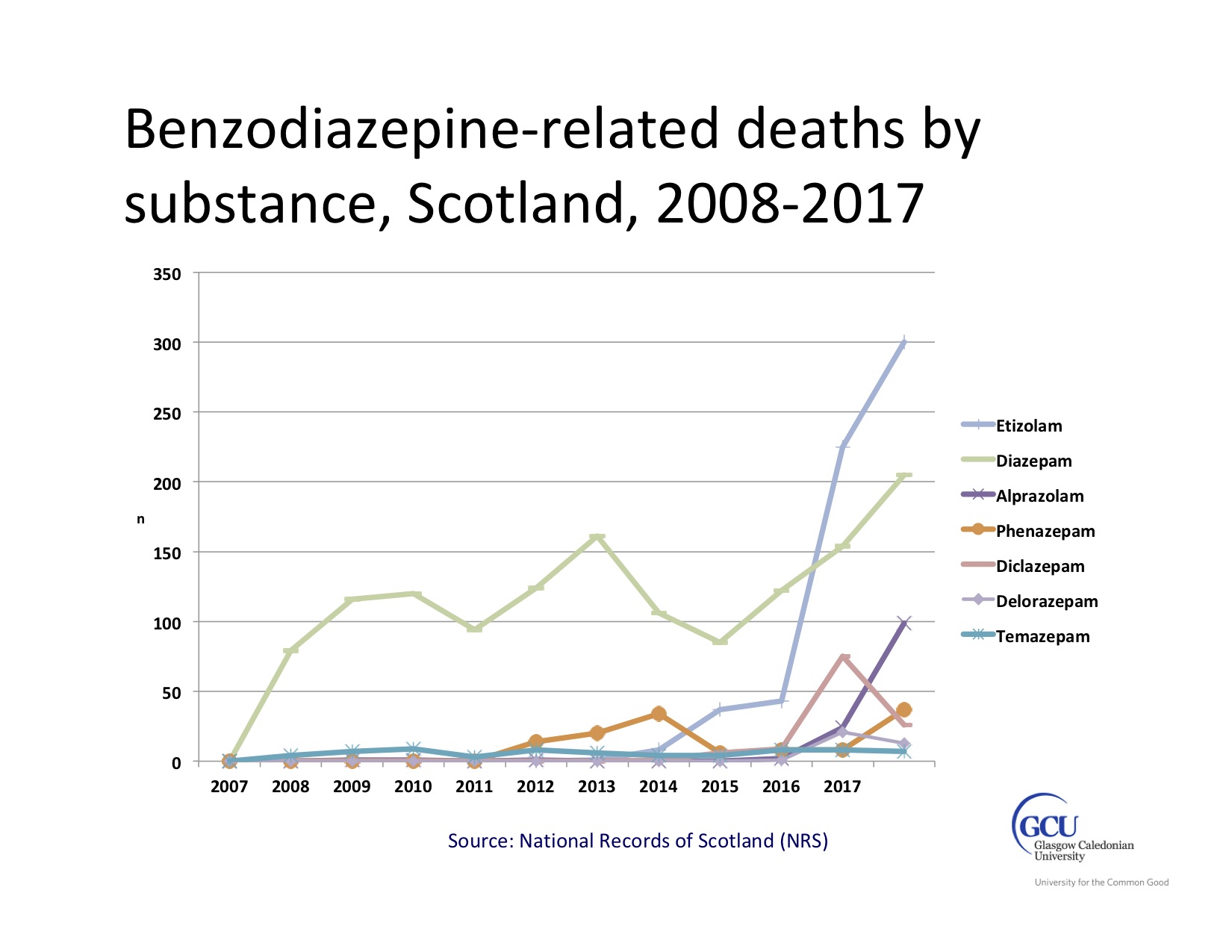

The first illegally-manufactured benzo to hit big in Scotland was a substance called phenazepam. Originally produced in the Soviet Union in the 1970s, it is not approved for medical use in the US or the UK. “That was the first illicit benzodiazepine in response to tighter prescribing,” recalled McAuley. Phenazepam is ten times stronger than Valium (diazepam), and the effects last longer.

According to McAuley, after phenazepam was added to Scotland’s official list of controlled substances, it was replaced by something at least as bad: etizolam, which is also ten times stronger than Valium, but lasts for a shorter amount of time, meaning that people take it more frequently. Worst of all, these varying substances were pressed into nearly identical pills that were made to look like and sold as though they were Valium.

“The thing that makes these [especially] unethical is that they are branded and marketed as diazepam. They are coloured the same way. They have the same markings,” McAuley said. Known as “street blues,” “street valium,” and “the blue plague,” they are so cheap that people tend to report their dosage as being “handfuls,” he added.

In 2017, benzodiazepines were involved in more than half of all drug deaths in Scotland, which have doubled in the past decade and are now at an all-time high.

In fact, demand for these drugs is so strong there that local players decided to start making them, rather than importing from China or other countries. Late last year, police raided a factory in a garage in Paisley, just outside of Glasgow, confiscating a pill presser worth nearly $26,000 (20,000 pounds) and over 1.6 million etizolam pills. The presser was capable of making 250,000 pills in a single hour—each with a street value of a little more than $1.

Despite prominent busts like that one, street valium remains easy to get, McAuley said.

Of course, a flood of stronger, more dangerous, and cheaper drugs was not what doctors and regulators were seeking when Scotland cracked down on benzos. Likewise, it’s not like Americans were trying to fan the fentanyl flames when they went after “pill mills,” and other easy sources of legal opioids. But waging a drug war has predictable, if unintended, consequences.

“The knee jerk reaction to the opioid OD crisis was to restrict prescribing,” said Dr. Scott Hadland, a pediatrician and addiction specialist at Boston Medical Center and Boston University School of Medicine. “But although that may have been the road into the crisis, it is not the road out.”

Americans would do well to keep these cautionary tales in mind as calls for restrictions on benzo prescribing take shape at the state and national level. Dr. Christy Huff is a director of the Benzodiazepine Information Coalition, an organization concerned with harms associated with using these drugs as prescribed. She said the group gets about 100 emails each month from people whose doctors have cut their medications down too quickly or cut them off entirely, without a referral to someone who would actually treat their anxiety and withdrawal.

“I think it’s getting worse,” Huff said. While her group aims to reduce overprescribing of benzodiazepines, unlike many advocates for reducing opioid access, they recognize that simply stopping the pills can do great harm.

For one, while opioid withdrawal is not often deadly unless someone is incarcerated and denied basic care like access to water or has other medical issues, benzo withdrawal can kill on its own by causing seizures.

Secondly, benzodiazepine withdrawal can last months or even years in some cases—and if tapers aren’t conducted slowly and carefully, people’s ability to function at home and at work can be destroyed.

Wendy Britt, a 47-year-old nurse from New Jersey, knows this all too well. She suffers from several chronic pain conditions and anxiety, but to her “delight,” she said, she found that she could wean herself off of Oxycontin and Vicodin by taking CBD, the substance found in medical marijuana (legal in her state) that is not associated with the “high” of weed.

As a nurse, however, she knew that quitting her anti-anxiety medication, Xanax, could be more dangerous. When insurance required her to change doctors and the new one would only offer one month’s supply to tide her over, she said, she called at least 30 other physicians with no luck. “And they wouldn’t give me information about helping me come off, either,” she said.

Ultimately, Britt had to take time off from work and check into a detox facility intended for people with addiction to get help—and six months later, she is only now beginning to feel better.

If we are going to prevent another fentanyl-type overdose crisis, this time led by super-strong street benzos, we need to avoid the mistakes we made with opioid policy. In fact, etizolam has already been found in the US—just as fentanyl was in sporadic cases before the current crisis.

First and foremost, medical patients who are currently on the targeted drugs and doing well need to be cared for, not simply thrown to the wolves.

Some will need to stay on these medications, and there needs to be a way to protect doctors who treat such patients from legal scrutiny over their doses and long-term prescribing. Many, if not most, will want to at least try to taper. But this needs to be done slowly and using evidence-based approaches, which often requires tapers that continue over months or even years. And all new prescribing must be carefully considered, time-limited if at all possible, and only permitted with informed consent about the difficulty of benzodiazepine withdrawal.

People who have been getting these drugs from physicians or pill mills for non-medical reasons like addiction shouldn’t be abandoned, either. According to McAuley, who’s on a committee advising the Scottish government, that country’s authorities have considered having physicians prescribe genuine Valium to people with addictions who are now at risk from the street version; American policymakers should consider doing the same. At the very least, no one should be simply cut off from benzodiazepines and left in potentially fatal withdrawal.

We now know as clearly as ever that cutting medical sources in the age of globalized supply chains can feed street markets and more dangerous, potent, and difficult-to-intercept products. We can put a dent in those markets by supplying treatment, including—for those who don’t yet want abstinence—maintenance on the drugs they are already taking.

America has a chance to get it right with benzos. We should take it.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Maia Szalavitz on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.