Kevin McAllister Is a Monster

Credit to Author: K.T. Nelson| Date: Wed, 26 Dec 2018 18:50:46 +0000

When I was growing up, we would spend every Christmas at my grandmother’s house. She didn’t have much in the way of kid’s entertainment, but she did have two holy grails of the season on hand: old VHS copies of Home Alone and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York. My cousins and I watched those things until we could recite every line from memory, and once we had done that, we just rewatched and rewatched and rewatched the best scenes in each movie: the traps. Kevin McAllister was our mad 10-year-old hero, setting up a trail of creative destruction that I thought every young boy dreamed of. It wasn’t until later in life that the real truth about these films dawned upon me: Kevin is a fucking monster.

For those of you who haven’t seen the films (you absolute shitheads), the originals center around a young boy who’s large and wealthy family has an unfortunate tendency to lose track of him (I lose my Apple TV remote all the fucking time, I’m sure it’s the same principle). In the first film, they leave him at their house as they travel for the holidays, and in the second, he somehow ends up in 1990’s New York City, alone and seemingly unconcerned about his prospects. In both instances, Kevin is beset by two bumbling burglars, Harry and Marv, who proceed to chase him around and all that. In many ways, this premise satisfied an ultimate childhood fantasy—being left in your home to do whatever you wanted. The “eat whatever you want, run around, blast music” ideal portrayed to us in films like Risky Business and the ilk. But it also revealed a deeper fantasy: the ability to set violent booby-traps with literally zero consequences for yourself or others. In my mind, every young person loves a good booby-trap.

Throughout the movies, Kevin traipses about his parents suburban mansion, The Plaza Hotel, and a monstrous Upper West Side brownstone, concocting this series of devious devices that vary wildly in severity. While each “prank” is treated as equally vexing for the two would-be robbers, you have to imagine that *a little glue and feathers gently blown onto one’s face* sounds significantly less painful than say, *multiple full cans of paint being dropped onto one’s head* or *an industrial flamethrower being fired directly into one’s ear*, both of which feel worthy of at least a hospital trip and a CAT scan. All of these things and more happen in very quick succession to the ill-fated Sticky Bandits, who nonetheless are generally undeterred in their quest to catch their tormenter.

The thing is, though: Kevin never needed to do any of that.

Was setting up a Rube Goldberg-ian set of Stand Your Ground ploys really easier than say, asking a neighbor to phone the police? Or simply phoning them himself? How about just asking to stay with a neighbor—no police involved (ACAB, after all). Of course not, because then Kevin would be forced to admit he was livin la vida loca solo-style, and that would bring his impromptu vacations to an end. Kevin is, at his heart, a spoiled, entitled, rich suburban brat who is willing to sacrifice his family’s home, and even commit murder, to avoid bringing his staycations or vacations to an end. In New York, he immediately seeks out the most expensive accommodations possible, thinking nothing of the cost it would leave for his parents. He watches as the bandits flood and loot his neighbors houses, saying nothing to their owners or the authorities lest they discover his cushy situation. He orders limousines, extravagant room service, and in one instance (for seemingly no other reason than his desire to inflict suffering) tricks a pizza delivery boy into thinking he is going to die, all for laughs.

Many of the traps Kevin sets up for the “villains” of the story are harmless and of the sort you might expect from a kid his age—the hot wheels on the floor, a tripwire, etc.—but some are decidedly much more sinister and in some cases, seem like he’s aiming for a more deadly end.

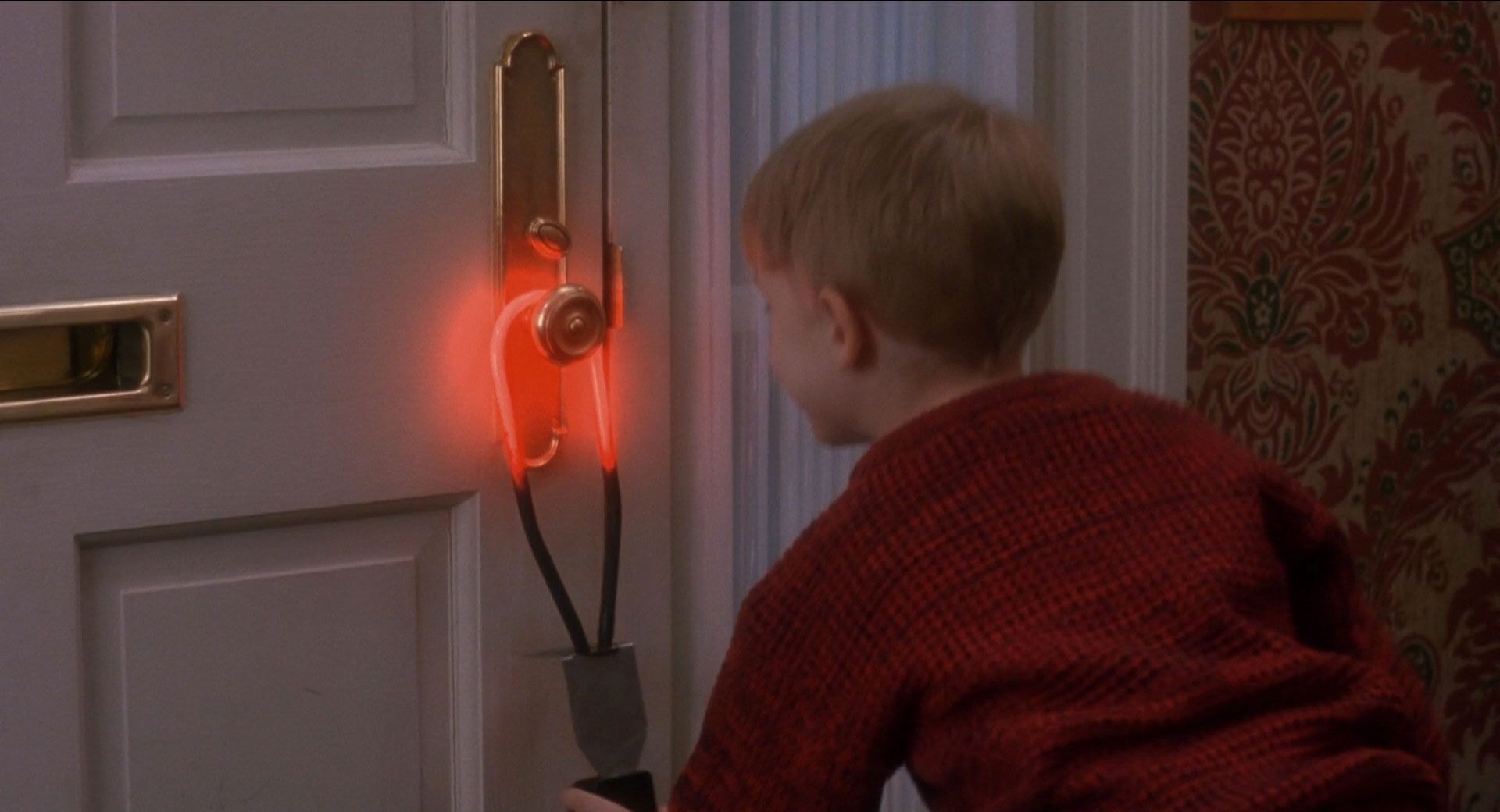

(Also, my entire childhood I mindlessly accepted that whatever this thing is was just a normal thing for a 10-year-old to have access to:

A doorknob heater I guess? Who the fuck knows.)

The bricks thrown at Marv’s forehead. The iron that falls four stories onto Marv’s forehead. The tar-covered spike that goes into Marv’s bare foot. Honestly it seems like Kevin just has a deep-seeded thirst for blood, and it can only be sated by the murder of a bumbling and loveable working-class stooge. He simply must kill Marv.

The key takeaway here is that there is no lengths to which Kevin will not go to extend his ill-gotten stay in personal Eden. No level of wanton property destruction, violence, or even manslaughter (I have a hard time believing the DA could get a murder charge to stick on a child of his age) can deter him from his quest to not spend Christmas with his family. Viewed through this lens, the movies become something different altogether: Kevin is a vile sociopath, who not only is willing to use such measures, but delights in them, laughing as he gleefully inflicts pain and suffering on whatever non-rich he happens to come into contact with. He is a spoiled little bitch of the highest order who cannot maintain normal human relationships—so much so that he does not seem to have a single friend—excluding the elderly, possibly mad bird lady who squats in the rafters above the New York Philharmonic.

And because he is a true spoiled rich kid, he also delights in that favorite activity of his ilk: suffering precisely zero consequences for his actions. Upon returning to find Kevin, his parents shower him with love and presents. They forgive the (presumably $6,000-plus) debt he accrued in New York. They overlook the insane amount of carnage he laid upon their family home. They don’t even seem to mind that he didn’t do anything to contact them the whole time. All is forgiven, and Kevin’s victims are left to pick up the pieces. That pizza delivery boy will probably suffer from PTSD for the rest of his life, but does Little Lord McCallister mind? Fuck no. He laughs whenever he thinks about it. So this Christmas season, as you sit down to watch these classic and beloved films, please try to remember that Kevin is not the hero of this saga—Marv is.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Krang T. Nelson on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.