What It’s Like to Be a Man Paid to Pretend to Attack Women

Credit to Author: Cole Kazdin| Date: Thu, 06 Dec 2018 18:45:32 +0000

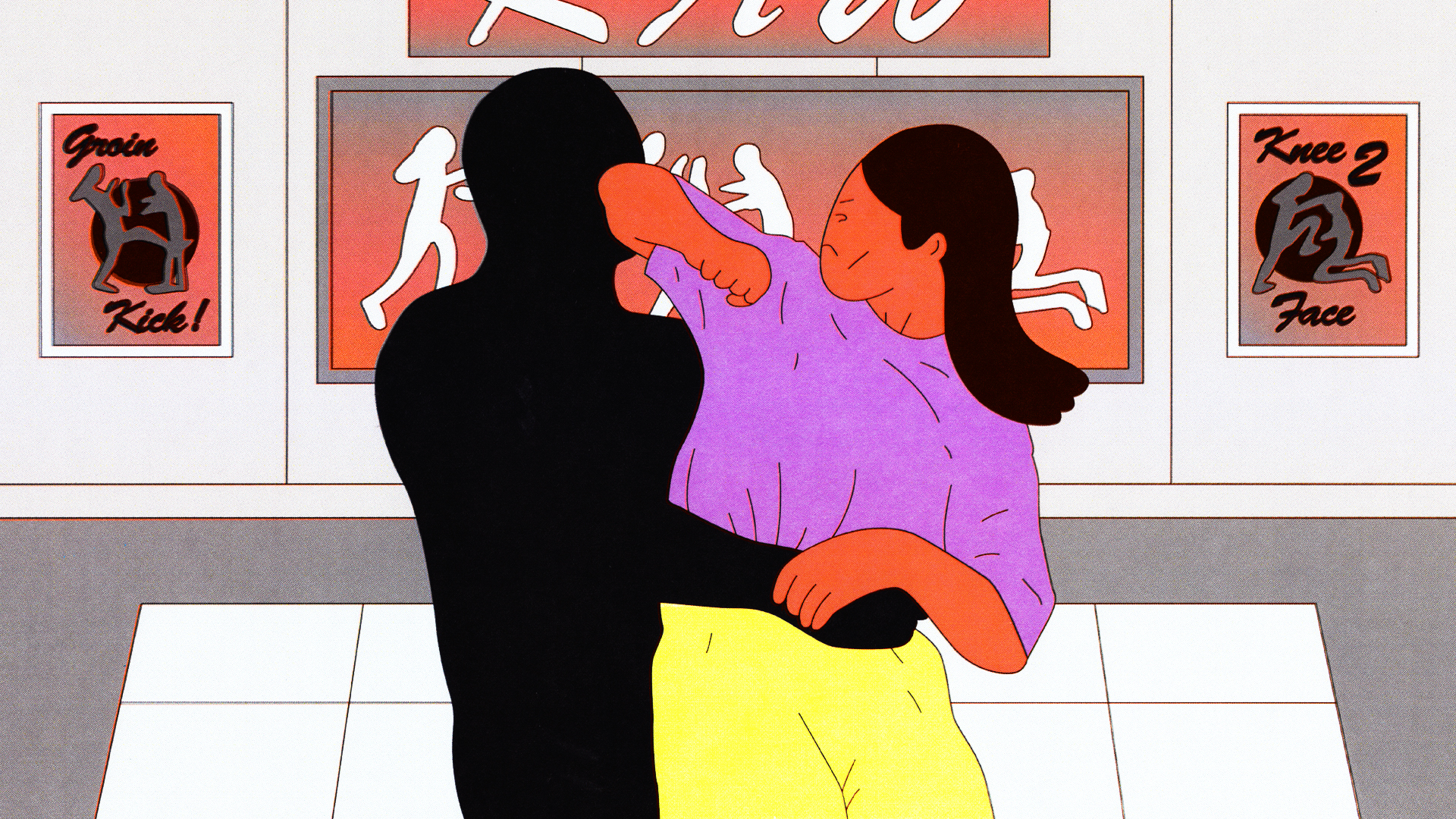

On a recent Sunday in Los Angeles, a dozen or so women gathered in a dojo for their first self-defense workshop. As they sat in a loose circle on mats waiting for class to start, they glanced nervously from time to time at three men standing on the other side of the studio. The men were stretching and talking quietly among themselves. Later that morning, they would put on protective gear, and, as realistically as possible, attack the women as part of the class.

It made for a tense beginning, even though all of the women, many of whom were sexual assault survivors, knew what they’d signed up for. They had paid for the authenticity; confronting real men, who were paid to insult them while pretending to attack, was the point.

“In terms of re-creating what’s really happening in the world, the vast majority of assaults are perpetrated by men,” said Meredith Gold, who runs the class, offered by RAW Power Self-Defense. “In keeping it as realistic as possible, and trying to recreate something that someone is most likely to encounter, the male energy behind the gear has always been extremely important.”

For the men, many of whom come from a martial arts background, it’s a tricky duality: They’re helping teach women physical self-defense skills, while also getting into character as the “bad guy.” In that way it’s very different from the regimented world of martial arts, where no one is ever supposed to call anyone a “fucking bitch.”

“We’re all very respectful in martial arts, bowing and helping,” said Mike Belzer, who has been practicing martial arts for over 50 years. When teaching self-defense, he said, “you have to learn how to say some pretty nasty stuff.”

That nasty stuff is a key component of what’s called “adrenal stress training,” the idea being that for a self-defense class to really work, it has to feel real. Most adrenal stress training is an offshoot of Model Mugging, which started in the 1970s and was originally intended to teach women to fight off rapists. These sorts of classes employ “assailants” wearing full padding and a helmet to withstand kicks to the head so that women can experience what it’s like to actually fight off attackers using full force. In the RAW Power class, the men assist in teaching physical moves alongside Gold, then when it’s time for practice scenarios, they put on helmets, indicating they’re in character.

In addition to learning moves like the eye-strike, head-kick, and knee-to-the-groin, women practice verbal sparring with the men and drill in de-escalating situations before they become physical. The men embody various asshole characters—sexual predator, angry guy in traffic.

“Look where you’re fucking going! Not your fucking phone, you bitch!” one of the men screamed as he crossed to the center of the room for a practice scenario, getting right in a woman’s face. She stepped back, put her hands up. Gold coached from the sidelines, reminding the woman of her script: Start by telling the man he’s too close to set a verbal boundary.

“The first couple of years it was very hard to take,” said Matthew Harris, a martial artist who has been teaching self-defense around Los Angeles for eight years. “I tend to be a very empathetic person and it was a lot to absorb.” Sometimes he’d say something to a student and she’d burst into tears.

Their scenarios are eerily realistic situations that women may encounter on a daily basis—unsolicited touching, “compliments” that quickly turn predatory, then physical. Harris said that he gets a lot of his ideas from real-life experiences that friends have relayed to him. “That’s what’s out there right now,” he said. “Let’s bring this to class.”

There are different levels to the RAW Power curriculum, and the level three class involves rape scenarios. In one, the entire mock-attack is on the ground, the man getting on top of the woman, then more or less mounting her from behind. “Those are the least favorite days, the least favorite classes to teach,” said Harris. “Even just to position yourself that way. Knowing you’re going to have to go in there and this is grossest stuff you’re going to have to do and knowing that it is 100 percent going to trigger everyone in the room. It’s—a lot.”

Before any fight scenarios begin, the men introduce themselves, and make a point to tell the women the reason why they’re there: to help and support. “The goal for the men is to communicate we’re safe,” said Belzer. “Sometimes you might have an ex-military guy or ex-cop want to be involved, but they come off a little—well, kind of like ex-military or ex-cop, not so open and supportive.”

The men who gravitate towards this work, at least the ones I spoke with, are drawn by altruism; they’re compassionate people and respectful of women. Which makes the switch into “character” challenging.

Rodolfo Valdés, who teaches self-defense at Defensa y Seguirdad Urbana Neuquén in Argentina, told me the physical instruction is easy. The other aspect of the course, not so much. In order to get into the character of the mugger or the rapist, he reminds himself that it ultimately will help the student. “No attacker will ever say, ‘Hey lady, please turn around,” he told me. “That would be unrealistic. So—” he paused for a moment. “You know the words.” He is so polite that he stopped our interview to ask if he can swear. After I told him it was fine, he unleashed in a tone lower and angrier than his natural speaking voice: “I’m going to kill you, you motherfucker… I’m going to rape you, you bitch.” He stopped, and switched back: “I swallow acid in my throat when I say those things. But my part is being the bad guy.”

“When we’re in the gear, we’re not to be trusted,” said Belzer. “We’re the bad guy. We will not say, ‘Hit me harder.’”

Many of women in the RAW Power class broke down into tears during scenarios, but kept fighting, with Gold and the others in the class cheering from the side. Belzer told me that most women, even the ones that break down or have to leave the room, are grateful to the “mugger” at the end of the day.

“It’s almost always a positive experience even when it gets emotional,” he said. “Because they’re re-creating situations that have happened to them and put a new ending on an old story. Or preparing for a real situation that might happen.”

It’s not uncommon for women to request a specific scenario from the guys, something that happened in real life that they can revisit with a new ending. After it’s over and the men remove their gear, the women often thank them.

“I was glad they wanted to challenge us with verbal assaults, and it was unexpected that they could even do it because they seemed so kind,” said one woman who asked that I not use her name. “The guys who taught the class were awesome people.” For her, the experience taking all three RAW Power classes was deeply meaningful.

“Some sort of shell broke,” she told me. “I remembered assaults I had never thought were assaults. In the moment of fights, I felt adrenaline pumping and didn’t think I could get out of situations and somehow miraculously did.” It’s reshaped how she moves through the world. “I feel empowered, I don’t feel scared.”

Kale Shepherd, who just recently started working as a “mugger” with RAW Power, told me it’s difficult to resist the urge to comfort a woman when she breaks down during or after an attack. “I have to have an understanding that because I’m a man, they might not want me to go up to them, put my hand on their shoulder and say, Hey, are you OK?”

The men, who as part of their training get mugged themselves, all said their work has given them a deeper understanding of and empathy for women.

“Women have to walk around with that fear all of the time, and I don’t,” Harris said. “When I walk out of the classroom, when I’m walking to my car, I’m not thinking of being targeted.”

Since the 2016 presidential election and the dawn of the #MeToo movement, the number of women taking self-defense classes hasn’t gone up significantly, Gold said, but more women are opening up in class about their personal survivor stories. And more men are interested in become instructors, Harris told me.

“Men can benefit from this just as much,” Shepherd said. “It’s very important for men to understand what women go through on a daily basis, and to come together. This is a problem we created and none of us want to talk about it. Now, with Judge [Brett] Kavanaugh—it’s important we start believing women, and working together so we can move forward.”

It can also be profoundly therapeutic. “To tell you the truth, I end up channeling a lot of the negative experiences I had with my dad,” Belzer told me. “My dad was quick to anger, he definitely intimidated our family. He was a good yeller, so when I get into character and I’m being the angry dude, that’s channeling a lot of energy I got from my dad.” In that way, the men are re-writing their own history too. “I feel like I can use some of those negative experiences I had for good.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.