The Strange, Brutal Connection Between Russian Prison Tats and Playing Cards

As research for his starring role in David Cronenberg’s 2007 film Eastern Promises, Viggo Mortensen sent the director a multivolume book: Russian Criminal Tattoos, a collection of prison body art from the London-based graphic design and publishing company FUEL. Mortensen thumbed through its pages because he knew, playing an up-and-coming gangster named Nikolai in the Russian immigrant underworld of London, that his character’s ink would tell his story—what jail he had been to, what kind of criminal he was, what fights he had won and lost. Russian prison tattoos are, after all, a sort of secret language.

During the film’s most notorious scene, when Nikolai takes a meeting in a steam room, a Kurdish associate remarks that Semyon, an elderly boss in the Russian mafia, often “recommends [a bathhouse] for business meetings, because you can see what tattoos a man has.” When two assassins attempt to kill Nikolai, he wards them off completely in the nude, and seeing all the images on his flesh adds to the enormity of the failed murder. Mortensen had insisted on being naked; he had done his tattoo research.

Now the people behind Mortensen’s source material have released a new photobook, Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards by Arkady Bronnikov. As the title promises, it explores the intimate, overlapping history of tattoos and card games in Soviet-era prisons. But the pictures also provide a glimpse of a lost culture, and of what life behind bars was really like in the old USSR, where a simple game could put you on the hook for someone else’s death—or cost you an actual eye.

VICE caught up with Damon Murray, one of FUEL’s founders, to learn about the relationship between these tattoos and playing cards, how they were made, what was at stake if you were a Russian criminal gambling inside prison, and why this culture has essentially vanished.

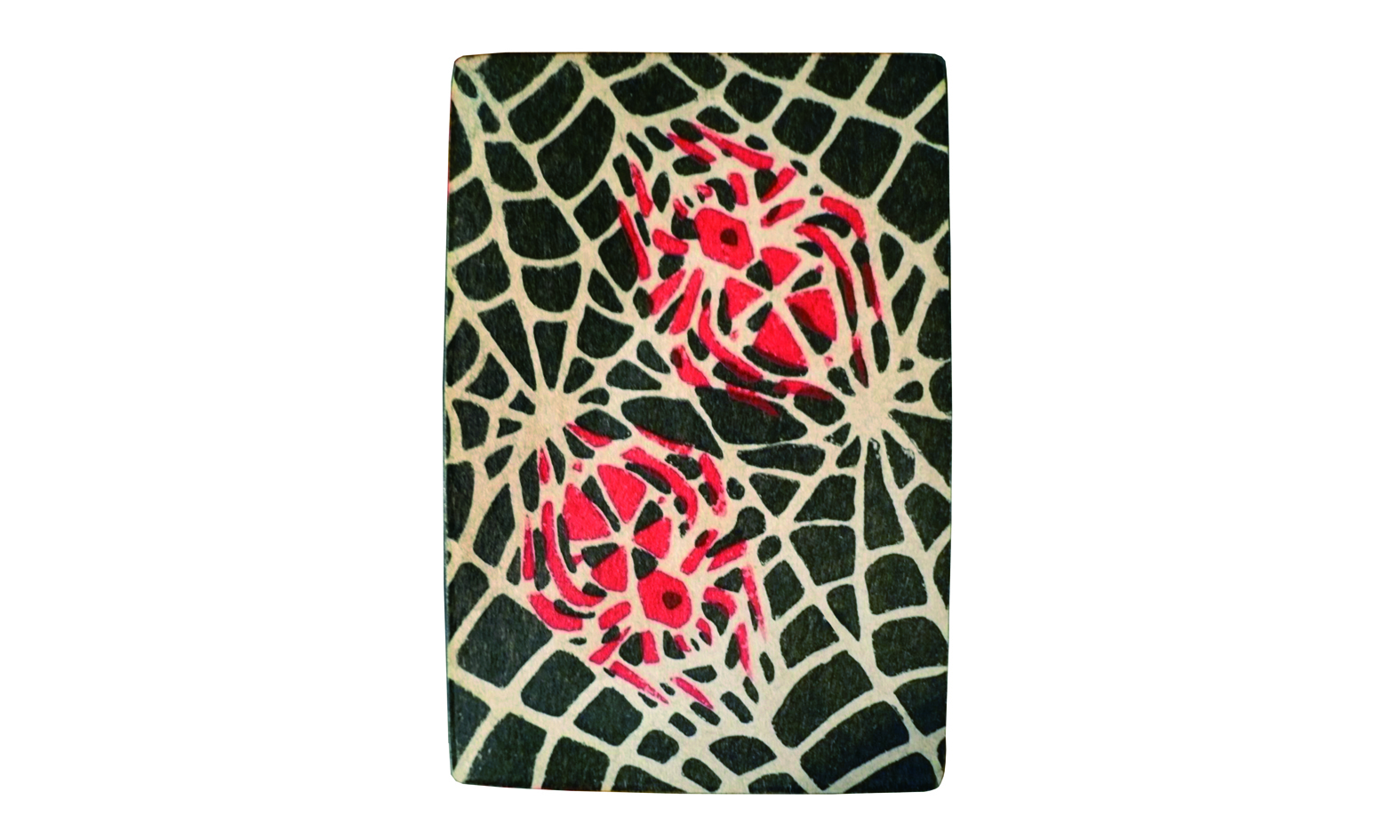

VICE: How—and why—were these playing cards actually constructed?

Damon Murray: Both the playing and making of cards in Soviet prisons and in the “zone,” as the correctional labor camps were known, was forbidden. If a card (or, worse, a whole deck) was discovered, the penalty was severe: To be involved in a card game was equivalent to defying the administration, consuming alcohol, or injecting drugs, and was usually punished with six months in an isolation cell. However, such penalties didn’t dissuade prisoners from gambling with cards.

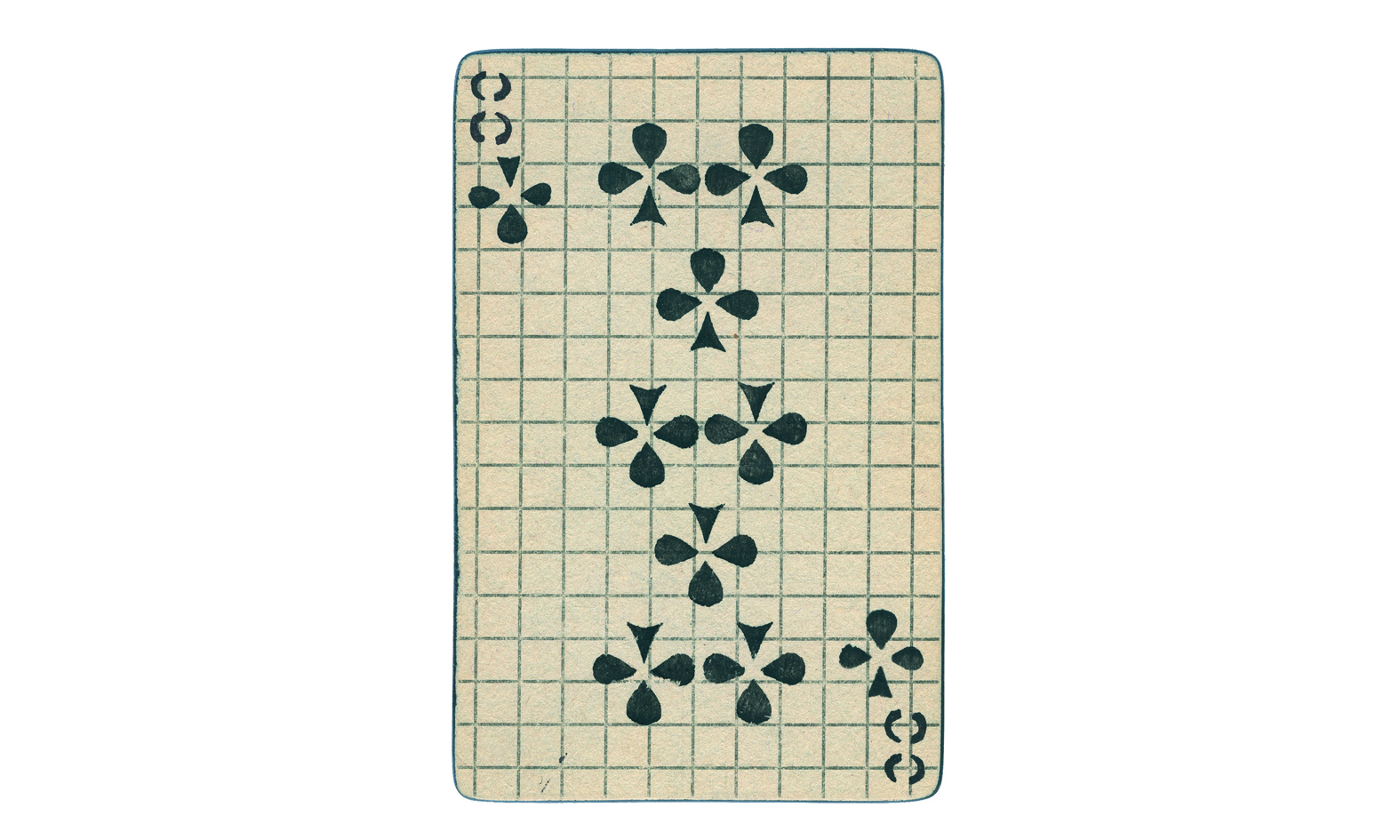

The cards themselves had to be made covertly from scratch. This highly skilled and laborious process began by sticking two sheets of paper together with glue made from chewed prison bread, passed through linen. These glued sheets were then flattened under glass until dried, when they were cut to size.

The next stage was to stencil. This was the first opportunity to mark them, so they might be “read” by their owner. The owner stipulated the type of stencil and paint he preferred. Soot was generally used for the black and a mixture of blood and bread glue for the red. (Blood was preferred as it dried darker than other prison inks.) The intention, here, was to make it as hard as possible for the opponent to comprehend the cards. In addition, texture might then be added to the ink, so the owner of the card could know the value before having to turn it over. After that, the back of the card was stenciled as well. Once the pack was totally dry, the cards were fanned out, and the edges sharpened with a piece of glass. This provided each card with a small new paintable area around the edge, where more—nearly undetectable—marks could be made to the specification of the owner.

What were the stakes of the games—what did people actually gamble with?

Usually, the stakes and method of payment were agreed on before the game. Tea or cigarettes might be wagered, but also fingers, ears, eyes, or even the lives of other inmates—or the life of the player himself. Criminals who gambled their body parts in a card game would do so to demonstrate their strength of spirit, bravado, and ruthlessness. When a thief lost his stake, whatever it was, the item had to be redeemed immediately. If he reneged, he would be labelled a suka (“bitch”) and knifed. In one particular case, a criminal who lost his left hand in a card game couldn’t bring himself to cut it off and tried to run away. The authorities recaptured him and had him transferred to another camp, but his fate was sealed. In his absence, he was sentenced by a skhodka (“a meeting of legitimate thieves”). The criminals found out where he had been sent and arranged for the sentence to be carried out there.

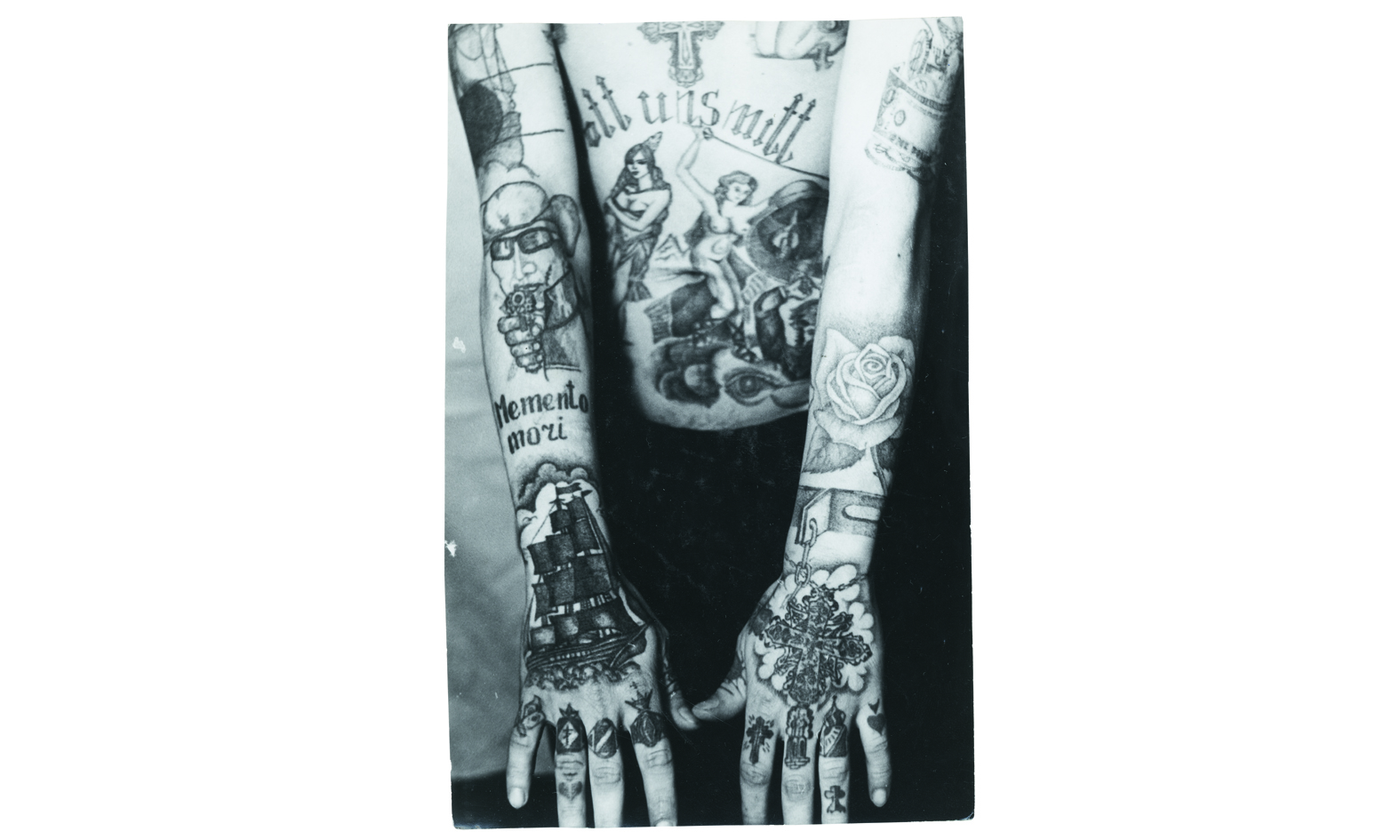

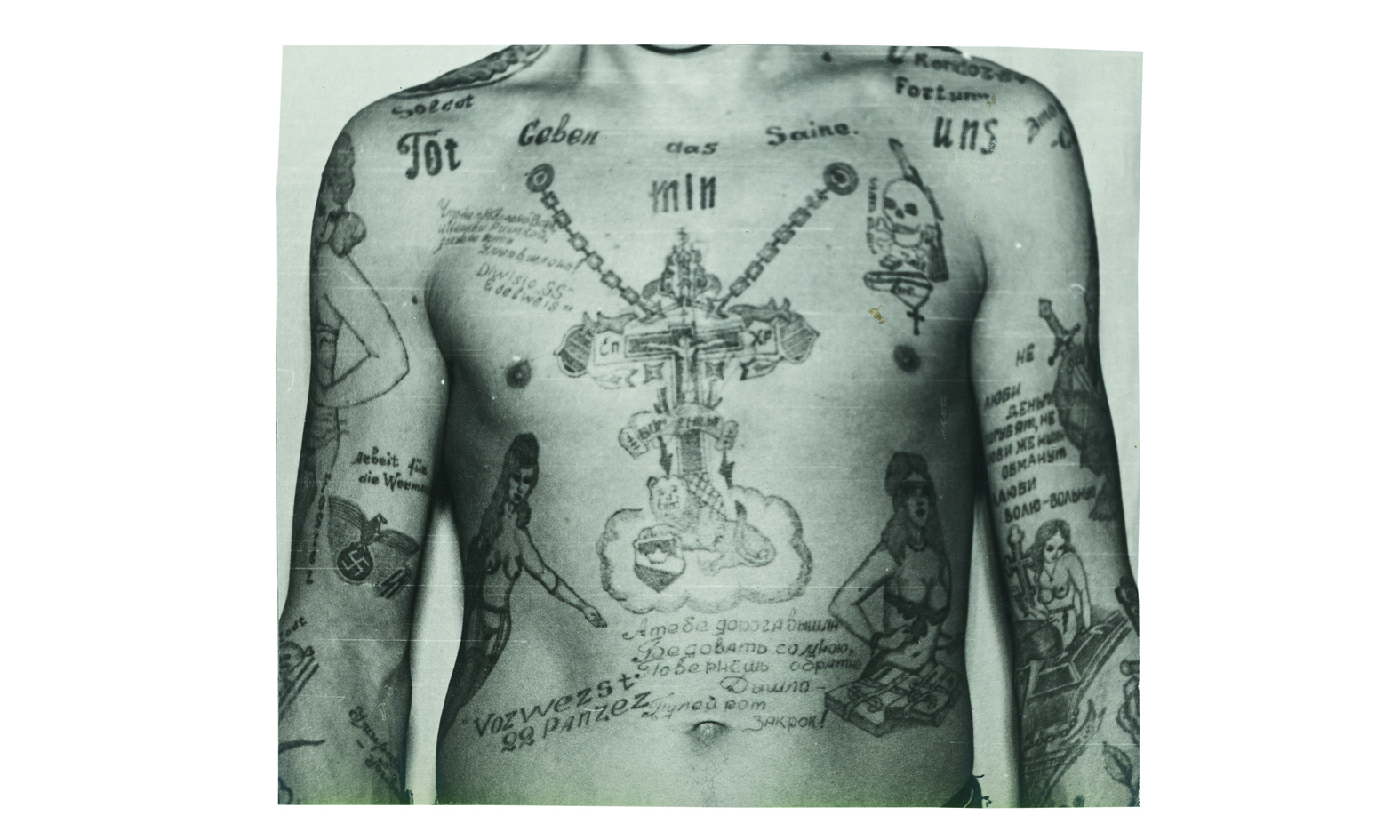

So what, ultimately, did these tattoos mean to Russians in prison—did they signify a gang allegiance, tell a story, mark life events? All of those?

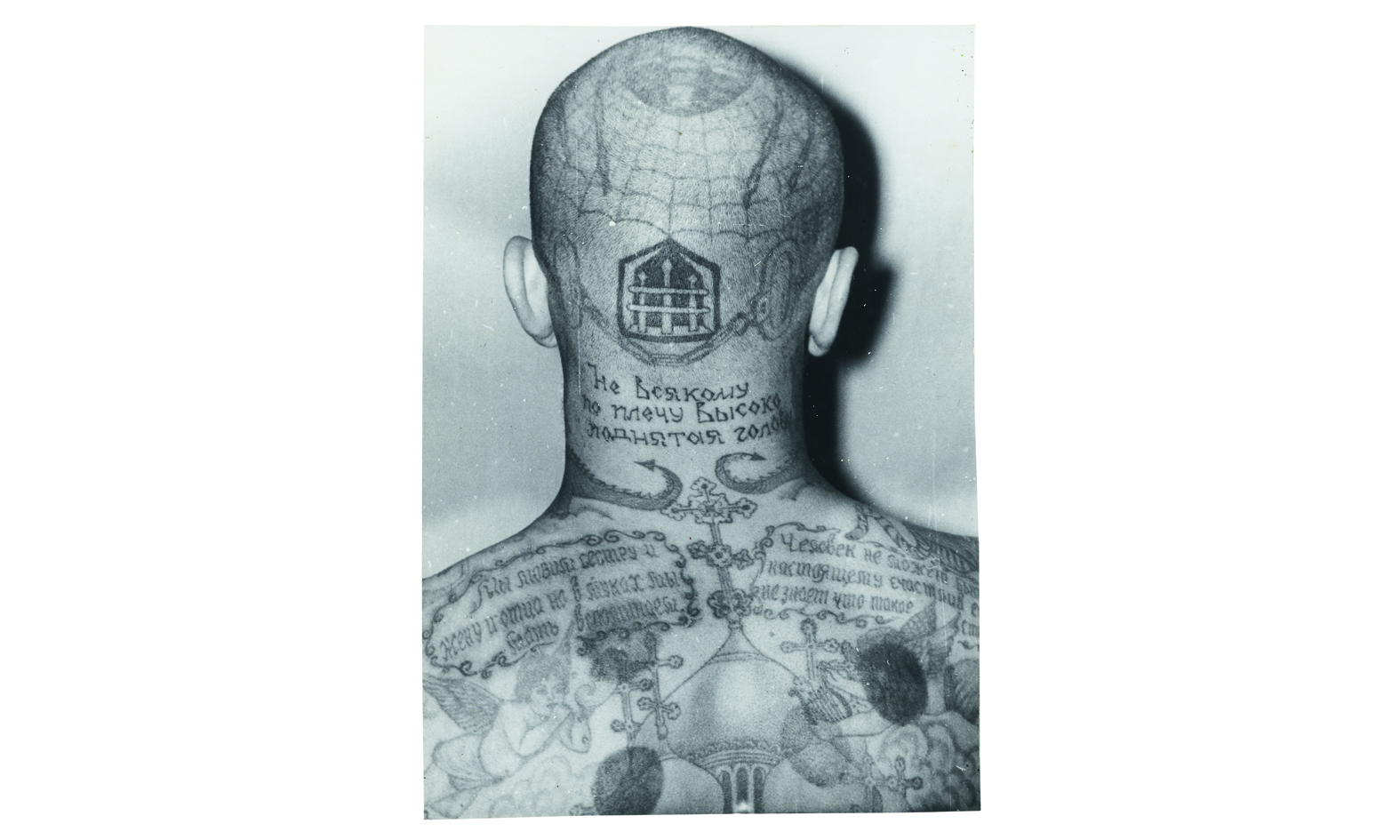

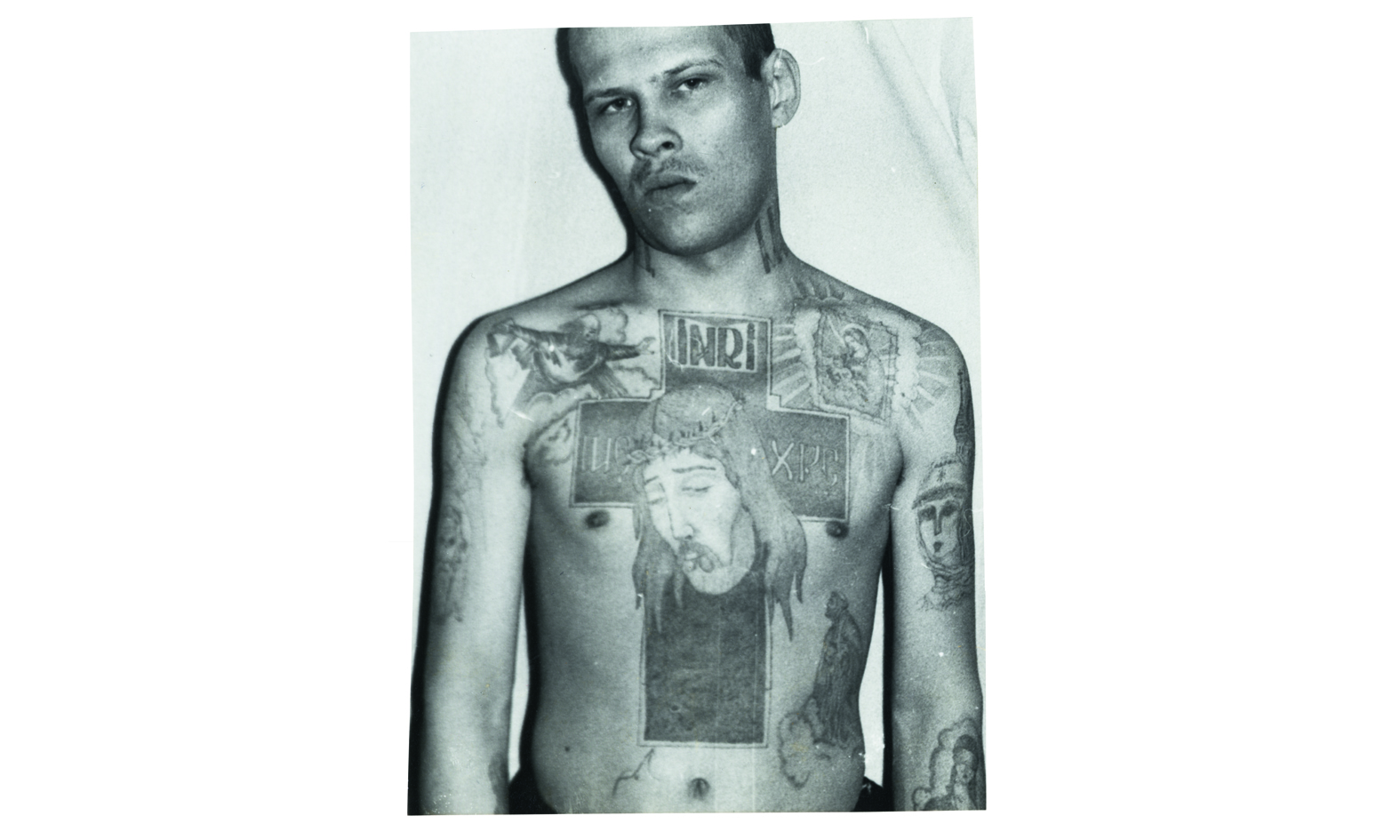

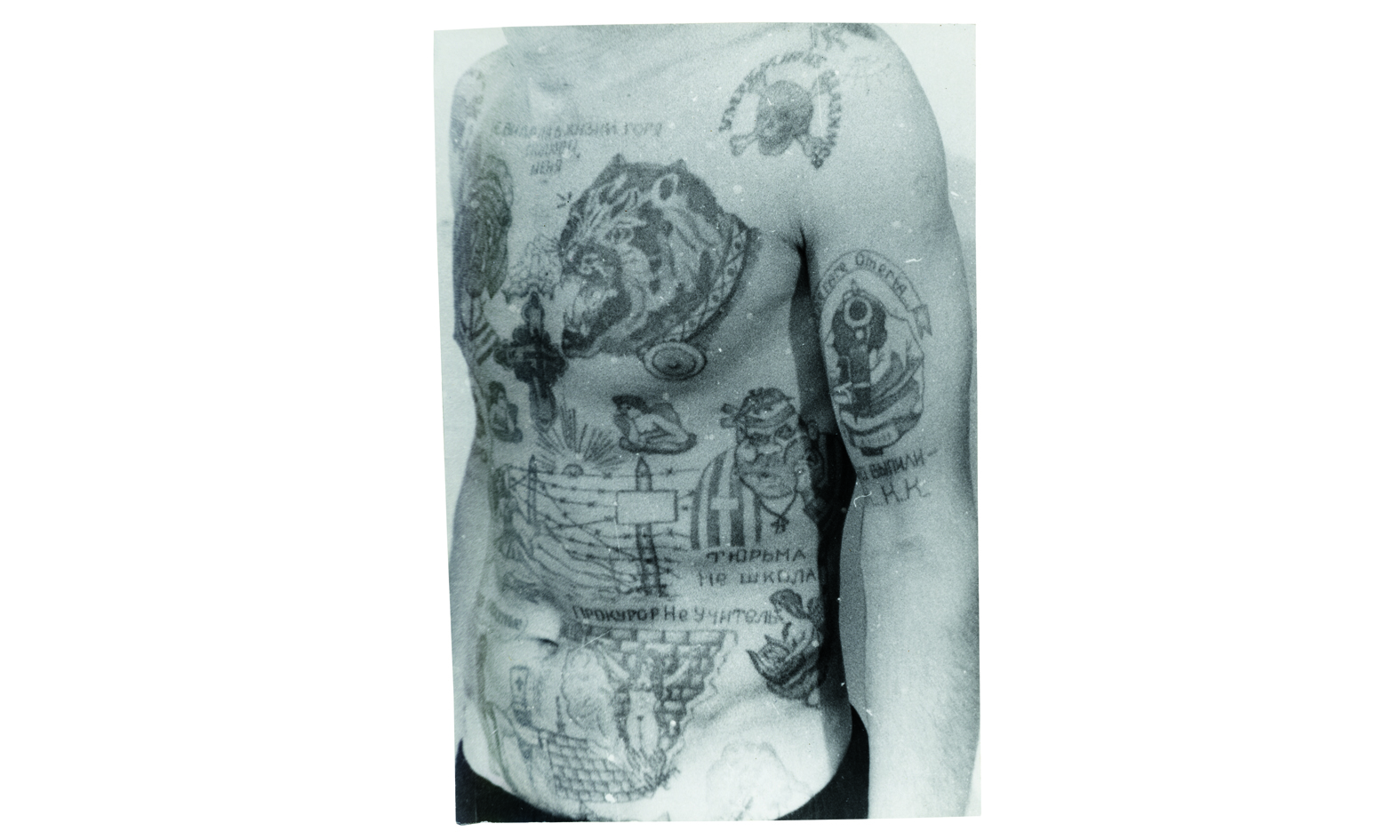

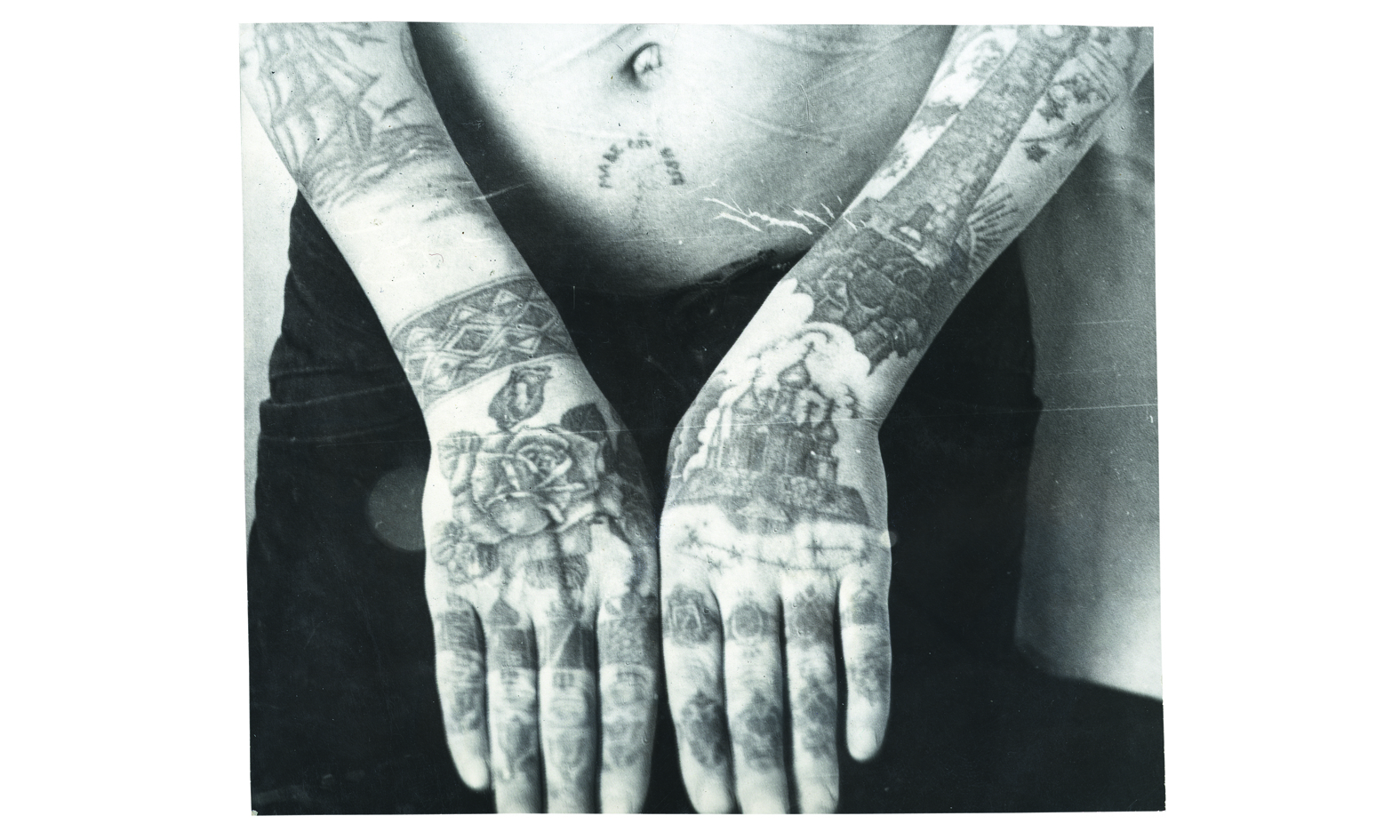

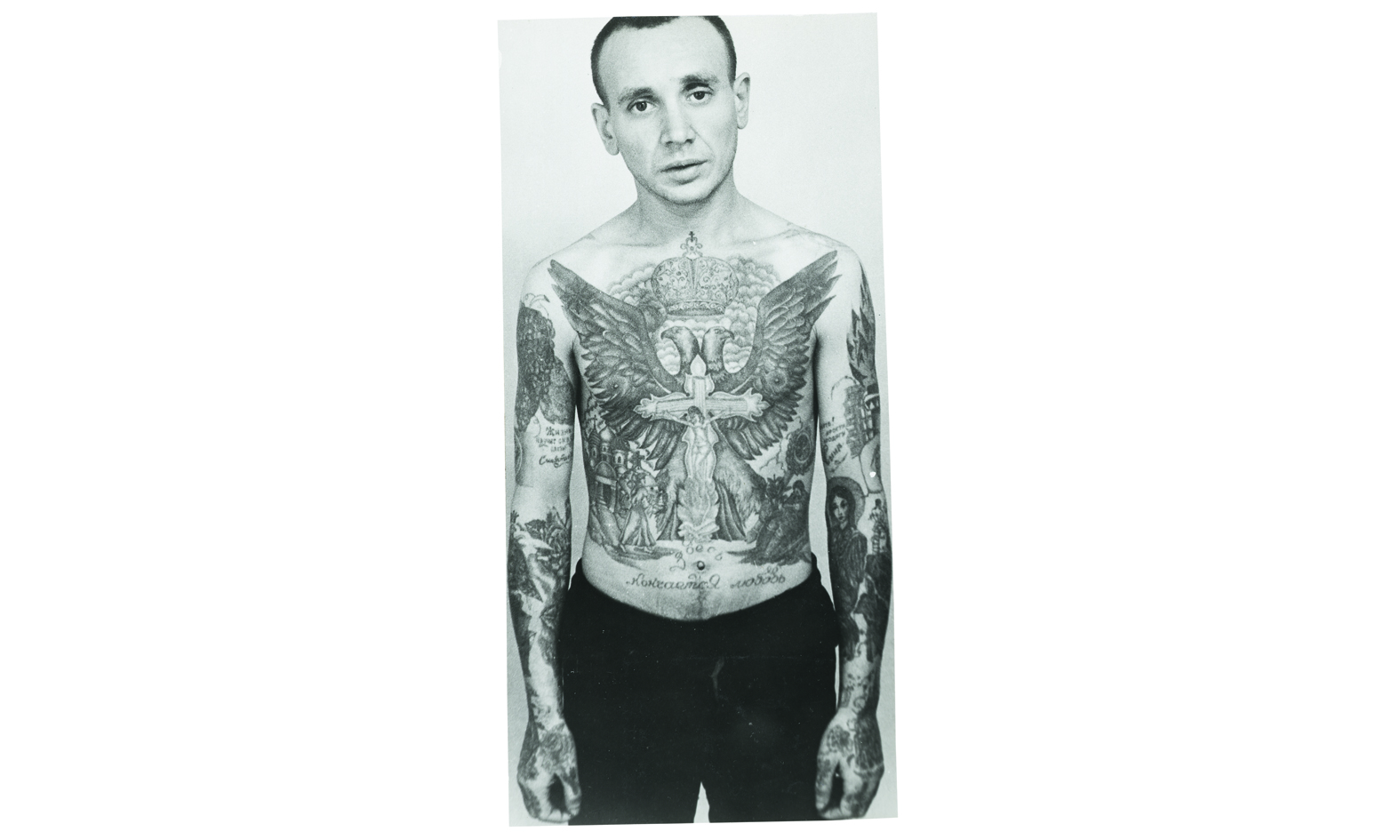

The tattoos in this book are essentially nonexistent in this form today. That’s to say, they don’t carry the same significance, because the punishments that made them “valuable” are no longer enforced. In the Soviet era, a thief’s tattooed body showed his status within the thieves’ world. The tattoos of a vor v zakone [“thief in law” or “legitimate thief”] functioned in a similar way to a depiction of a full-dress uniform, covered with regalia, decorations, and badges of rank and distinction. In thieves’ jargon, the traditional set of tattoos was known as a frak s ordenami (“a tail coat with decorations”). These tattoos conveyed secret, symbolic information, which at first glance may have appeared familiar to everyone—a naked woman, a devil, a burning candle, and so forth.

These images embodied a thief’s complete service record, his entire biography. They detailed his achievements and failures, his promotions and demotions. They told the “truth” about that inmate, if you will. They were his passport and case file, the key to his survival. As soon as a normal inmate entered the mass population of the zone, they quickly realized the thieves were in charge. Then, they would copy both their tattoos and mannerisms in an attempt to elevate their status. For self-protection, they needed to show themselves to be exceptional, experienced, brave, and seasoned men.

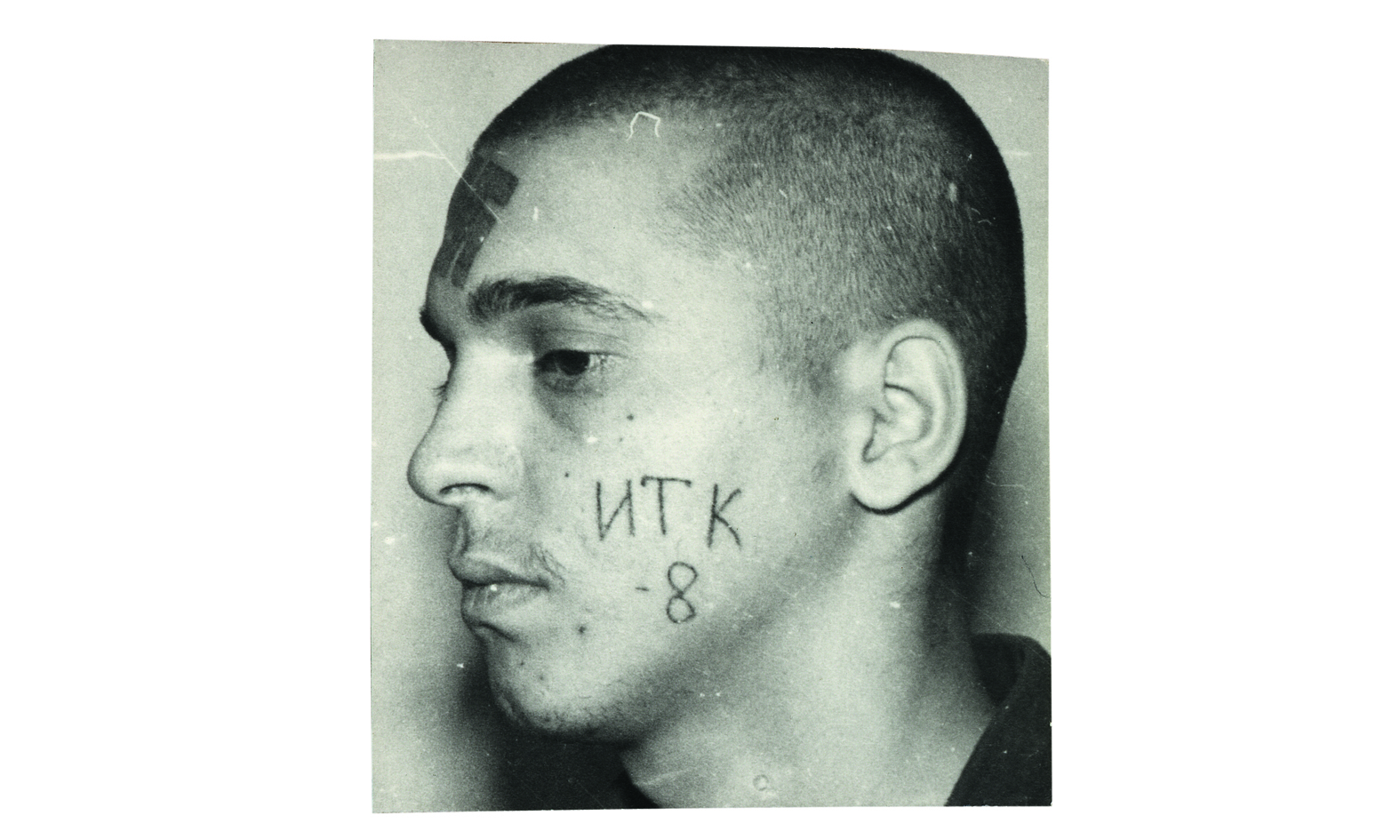

The question asked by legitimate thieves of any new arrival was: “Do you stand by your tattoos?” If the tattoos did not reflect his rank, the prisoner was forced to remove them with a knife, sandpaper, a shard of glass, or a lump of brick. He was consequently beaten, raped, or killed. In the world of thieves, a man with no tattoos had no social status whatsoever.

So with that dense symbolic structure already in place, what do cards add to it?

Groups of inmates belonged to different masti (“suits”), and these card symbols were represented in their respective tattoos. The most noble of the cards were the king of clubs and spades. The main symbols of a legitimate thief were suits of clubs or spades. In contrast, the red suits were the least noble. Stool pigeons belonged to the “chummy” suit, represented by a diamond, while the symbol of hearts transformed the bearer into a “woman” in the zone. Both of these symbols were forcibly applied, depriving the bearer of all status, leading to violence. These signs served to enforce the power of the thieves, acting as a warning to the rest of the prison population. Should other inmates associate with them, their own status would be “lowered.”

Allegorical images were used within the language of the tattoos to convey messages about the bearer. For example, images of copulation would be tattooed on the body of a thief who failed to pay his debt at cards. These tattoos were a punishment. Meanwhile, a thief who was a skilled card sharp might have had the symbols of clubs, spades, diamonds, and hearts tattooed across the knuckles. In Russian, the first letters of any given suit comprise the phrase Kogda Vyidu Budu Chelovekom (“I’ll be a man when I get out”), confirming the bearer’s intention to follow a criminal path.

How did Bronnikov, a criminalistics expert formerly of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs whose work comprises much of your collection and who authored the book, amass such an extensive array of tattoo pictures?

So part of his duties involved visiting correctional institutions in the Ural and Siberia regions. It was there that he interviewed, gathered information, and took photographs of convicts and their tattoos, building one of the most comprehensive archives of the phenomenon. This material was exclusively for police use, to further the understanding of the language of these tattoos and to act as an aid in the apprehension of criminals in the field.

These cards, however, are not from the Bronnikov collection, but have been accumulated by FUEL over the past decade. Because they were confiscated and destroyed by the prison authorities, original decks are difficult to obtain and often incomplete. Originals are usually characterized by their small size, about the thickness of a packet of Prima cigarettes. Such cigarette packets were commonly used to store the cards as they were perfect camouflage.

Has tattoo and card culture in Russian prisons changed after the downfall of the Soviet Union? By which I mean: Is this sort of thing still happening at all?

To answer this question fully, we have to go back to the 1950s, when the thieves code (the set of rules or understandings by which they led their lives) was at its most stringent. At that time, the punishment for wearing a tattoo you hadn’t earned might be a beating, rape, or even death. By the late 1960s, these cruel retributions had turned against the legitimate thieves. There were so many shamed prisoners (inmates who had been lowered in status by rape) that the authorities used them as a weapon against the legitimate thieves, who were thrown into cells populated by their victims.

Eventually a council of thieves passed the “no punishment with the penis” rule, which prohibited any of their number from lowering (i.e. raping) prisoners in this way. This led to an easing of tension and the gradual disappearance of punishments for wearing illegal tattoos. The fashion for tattooing swept through juvenile prisons, whose inmates covered themselves with every design and inscription, including trademark thieves’ tattoos. Realizing it was impossible to enforce their laws on the youth who were so in awe of them, the thieves gave up—allowing the freedom to tattoo whatever they liked.

With the arrival of perestroika (the “restructuring” led by Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet government), many tattoo parlors opened across Russia and the total number of tattooed inmates substantially increased. Drugs also had an effect on the tattooing tradition in prisons, allowing inmates who dealt in this lucrative trade to buy whatever tattoo designs they desired.

Contemporary Russian criminals are much less likely to be tattooed. Where previously these marks acted as a sign that the bearer belonged to the caste of thieves and adhered to the thieves’ code, today they act as both a method of identification for law enforcement and a hindrance to the business world, the real aspiration of the modern Russian criminal. With so many professional tattoo parlors, it’s becoming increasingly rare to see original prison tattoos. The tattoos of today’s Russian criminals are more likely to be done in a professional studio and carry personal meanings, not those of a strict code that can be understood by others.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.