U.S. Biomass Power, Dampened by Market Forces, Fights to Stay Ablaze

Though experts say biomass should continue to play a key role in the U.S. renewable power portfolio for its baseload properties, contributions to forest management, and other reasons, a swathe of uneconomic biomass power plants across the U.S.—especially in the West—have been recently idled or shut down.

While the larger conversation about plant economics and mass retirements in the U.S. has been focused on coal and nuclear power plants, the nation’s much smaller biomass power industry is grappling with similar issues in markets where cheap natural gas, wind, and solar generation resources are proliferating.

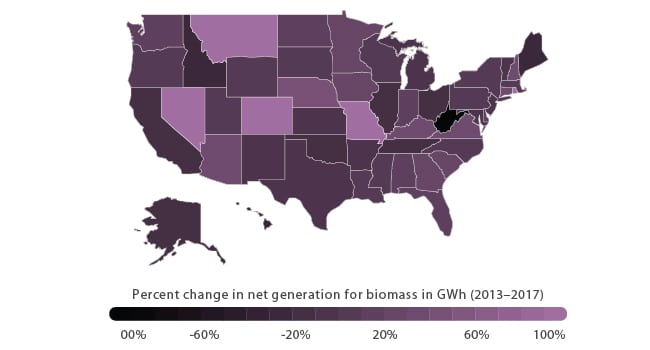

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the number of biomass (or biopower) plants producing electricity from combustion, co-firing, gasification, anaerobic digestion, and pyrolysis, nearly doubled between 2003 and 2016 (from 485 to 760). Yet, biomass power accounted for only 1.6% of net U.S. electricity generation in 2017, producing 64,057 GWh. Production has fluctuated slightly—and varied widely by region (Figure 1)—since 2013, when the industry produced 60,858 GWh.

1. Going dark The 10 states that produced the most net biomass generation in 2017 were: California (5,911 GWh); Florida (4,941 GWh); Georgia (4,917 GWh); Virginia (4,035 GWh); Alabama (3,377 GWh); Maine (2,930 GWh); Louisiana (2,796 GWh); South Carolina (2,687 GWh); North Carolina (2,633 GWh); and Michigan (2,578 GWh). Over the past five years, Virginia’s net biomass generation surged 39%; Georgia’s, 29%; South Carolina’s, 21%; Alabama’s, 17%; and Florida’s, 11%. But California’s net biomass generation shrank 11%; Maine’s, 24%; and Michigan’s, 5%. Fourteen other states saw decreases, including Idaho (29%); Illinois (19%); and Texas (10%). Source: EIA/POWER

[Interactive Chart: Change in U.S. Biomass Generation (2013 to 2017)]

Snuffed Out by Shifting Market Winds

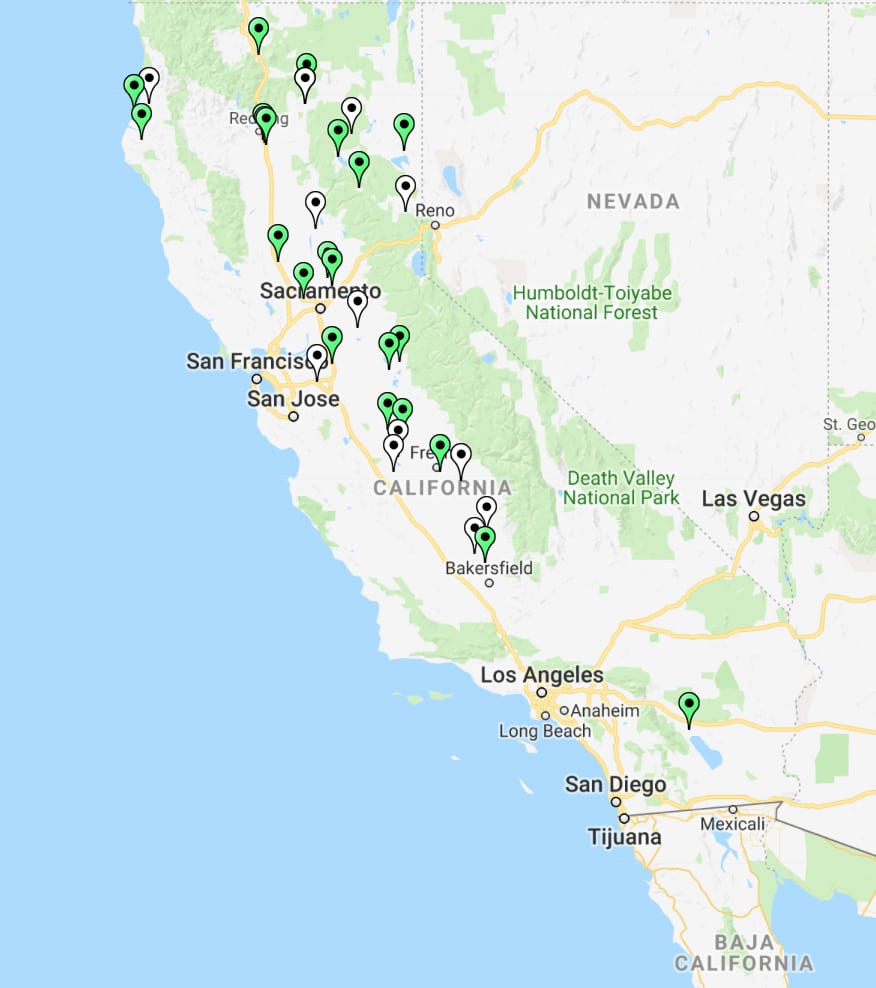

The predicament is most apparent in California, where, despite a flurry of measures to prop up biopower, net biomass generation has shrunk by 11% since 2013. While nearly 530 MW is online in the state, about 200 MW remains idled. These include sizable projects like the 48-MW Covanta Delano plant and the 25-MW Covanta Mendota plant. About 100 MW is ready to come online as needed within 30 to 90 days, Julee Malinowski-Ball, executive director of the California Biomass Energy Alliance (CBEA), told POWER in September.

According to the California Biomass Energy Alliance (CBEA), half the nation’s biomass industry calls California home. But of 34 operating solid fuel biomass power plants located in the state’s 19 counties, nearly 530 MW is online and about 200 MW remains idled. Source: http://www.calbiomass.org/facilities-map/

The situation facing biomass projects in California—a state that just pledged to produce 100% of its power from renewables by 2045—was mostly price-related, she noted. “[O]ur Renewable Portfolio Standard [RPS] is designed generally, for the most part, to be technology neutral under the guise of ‘least-cost, best-fit,’ but no utilities are procuring renewables based on that combined assessment,” she said. “They’re just buying the cheapest renewable out there and that isn’t your baseload renewable resources like biomass and geothermal.”

No specific resource is available to pinpoint just how many biomass facilities have been idled or are financially flailing, but recent announcements are telling. Among facilities showing distress in the face of cheap gas is the 2013-opened 102.5-MW Gainesville Renewable Energy Center in Florida, whose merchant energy owners in November 2017 sold the facility to Gainesville Regional Utilities (GRU), which had a power purchase agreement (PPA) with the facility, in a $754 million deal. In Virginia, where Dominion Energy converted a handful of coal-fired power plants to biomass over the past five years, three 51-MW units—Altavista, Hopewell, and Southhampton—“make economic sense to run because with cheaper fuel, tax credits, and renewable energy credits, these are very competitive,” and are actually bid into the PJM market as baseload units, a spokesperson told POWER in May.

Dominion, however, in August placed its 1994-completed 83-MW Pittsylvania Power Station into cold operation because it no longer receives tax credits and is not as competitive. The project could be retired in 2021, the company said. After the Minnesota Legislature in 2017 scrapped a biomass mandate for utilities, Xcel Energy in April cleared potential roadblocks to buy and close the 55-MW Benson power plant in Minnesota (Figure 2), whose power it was obligated to buy under a PPA. The company also moved to terminate PPAs for 35 MW of biomass in Hibbing and Virginia, Minnesota.

According to consulting firm Innovative Natural Resource Solutions, biomass plants in the Northeast have also been particularly hard-hit because prices for natural gas and heating oil are at recent lows—“and there is no reason to think this will change in any meaningful way.”

Roiled by Policy Conflicts

Some states have implemented measures to stem the financial bleed, the firm noted. Maine’s legislature, for example, in 2016 passed a bill to provide nearly $14 million in above-market payments to sustain biomass operations at its six standalone plants, and the state’s Public Utilities Commission (PUC) in April 2018 also voted to approve a portion of a subsidy meant to keep two stranded wood-to-energy power plants owned by Stored Solar LLC alive.

In New Hampshire, the Legislature on September 13, 2018, narrowly voted to override Gov. Chris Sununu’s June 2018 veto of Senate Bill 365, which requires electric utilities to buy power from six of the state’s independent but loss-making biomass power plants for three years. The projects consume more than 40% of all low-grade timber harvested in the state each year, and the veto prompted at least three biomass power companies to stop buying wood chips from local suppliers and switch their plants to reserve status.

In Connecticut, the future looks murkier for Greenleaf Power’s 37.5-MW Plainfield Renewable Energy facility, which was completed in 2013 as a result of a state-sponsored procurement for baseload Class I renewable energy through the Project 150 program, after the state in March released its Comprehensive Energy Strategy, which plainly supports development of “zero-carbon” resources and aims to phase out biomass and landfill gas renewable energy credits (RECs). Meanwhile, ReEnergy in December 2017 announced it would shutter the 1992-opened 22-MW Lyonsdale energy facility in New York, after the state failed to act to renew its eligibility to sell RECs.

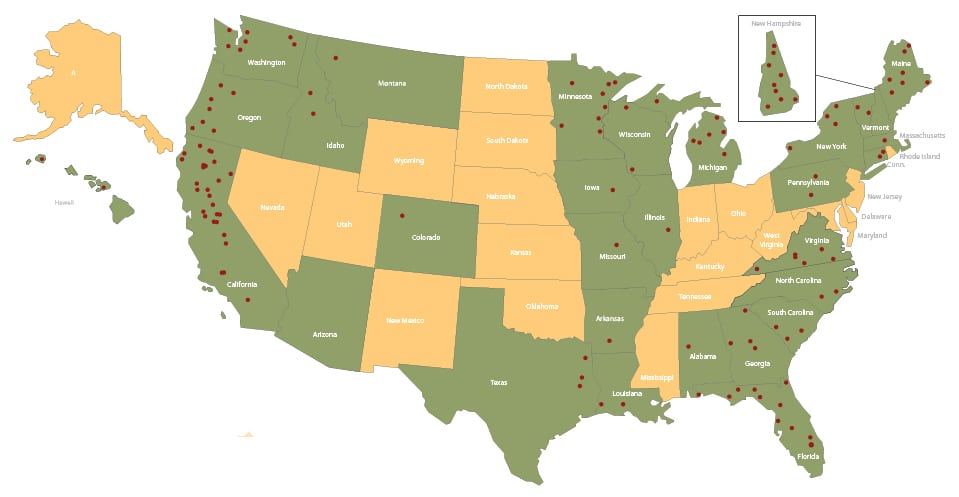

Map of U.S. biomass power facilities (March 2017). The facilities indicated on this map use wood and other byproducts to generate power for sale on electric grids. Source: Biomass Power Association (www.usabiomass.org)

An Environmental Pushback

Making matters worse, the biomass power industry is also fighting to thwart an environmental group campaign that contests the carbon neutrality of wood-burning plants. Activist opposition kicked up following the release of a widely cited and highly controversial Manomet study in 2010—which found burning forest trees for power can release more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere per unit of energy than oil, coal, or natural gas—and Massachusetts in 2012 issued rules limiting RECs to only biomass plants that adhere to climate standards and consider forest impacts.

However, this April, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stepped into the debate, declaring it would treat biomass from managed forests as carbon neutral when used for energy production stationary sources. Meanwhile, the apparent demise of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan—which prompted biomass co-firing (with coal) or standalone plants in “wood-basket” states like Arizona, Oregon, Washington, Minnesota, and others—may not turn out so badly for the industry. While the proposed Affordable Clean Energy rule does not prescribe biomass fuels as a best system of emission reduction—“because too few individual sources will be able to employ that measure in a cost-reasonable manner”—the EPA solicited comments on use of both forest and non-forest biomass as a compliance option.

Another consideration with implications for biomass economics is that some plants, especially if used for combustion or co-firing, must also abide by federal and state pollution rules, which sometimes require expensive upgrades. As Malinowski-Ball noted, California industry has already installed multimillion-dollar pollution equipment or “is open” to upgrading emissions control equipment—but only if long-term contracts are an option. “If a facility just gets a three-year contract, no bank is going to say, ‘here’s all this extra money to put in an electrostatic precipitator,’ ” she said. The industry is addressing that with policymakers, touting biomass’ bigger environmental benefits, such as for forest management.

Managing Feedstock Availability

Another issue forcing plants to pare down power production—and even idle, or shut down—is a volatility in feedstock availability and pricing. As Eric Kingsley, a partner at Innovative Natural Resource Solutions, noted, wood fuel isn’t like other energy commodities, which means it doesn’t have the benefit of a transparent, real-time price discovery system. Suppliers range in size and credit-worthiness. But though prices often fluctuate, “they are remarkably stable” over time, panning out to be cheaper, with a lower rate of inflation, and significantly less volatility than oil and natural gas, he said in an August column for Biomass Magazine.

However, as with other fuels, biomass availability can be impacted by weather and seasonality, he noted. Biomass is also a low-value forest product, which means that because it generates little revenue for landowners: “Nobody is trying to grow biomass, and nobody wants a biomass-only harvest,” he said. Kingsley also pointed out that the industry must deal with transportation costs, including current constraints in trucking capacity. Yet, securing a stable supply isn’t impossible “with thoughtful planning and simple risk mitigation,” he said.

A New Purpose: Wildfire Mitigation

In California, at least, the biomass industry is taking a novel approach to address its threatened viability. “We’re never going to be ‘least-cost,’ and utilities never actually take a look at ‘best-fit.’ And when we look at the RPS, we know under this scenario no utility is ever going to procure more biomass,” she said. “But we know biomass has benefits far beyond the renewable electrons.” Biomass power, for example, has a tremendous potential to help manage forests, she said, noting that California, along with several Western states, is battling more frequent and increasingly devastating wildfires, and the state is pushing hard to address the issue proactively.

Gov. Jerry Brown issued a “Tree Mortality” proclamation in 2015, and in 2016, he signed SB 859. The measures direct the state’s three investor-owned utilities to enter into five-year contracts (under the BioRAM program) to get a total of 146 MW from biomass facilities that source fuel from forest materials removed from specific high-fire-hazard zones. As of 2017, the utilities exceeded the required procurement: Pacific Gas and Electric held 63 MW; Southern California Edison, 66 MW; and San Diego Gas and Electric, 24 MW. And this August, state lawmakers passed SB 901, a bill that allows utilities to use customer payments to help underwrite the cost of wildfire liability as well as to extend BioRAM contracts by five years.

However, that measure, too, has critics. California Public Utilities Commission President Michael Picker in an August opinion penned for CALmatters said that many biomass plants “are not well-suited to use fuel from high-risk fire areas since it is difficult to deliver sufficient fuel without incurring prohibitive costs, even if electric customers pay a premium for energy.” Increasing biomass would also necessitate building new lines to transmit power to customers, which could be costly. Meanwhile, public agencies have become the major supplier of wood as the California timber industry has shrunk, and most have limited budgets to log and remove dead trees, he noted.

‘Disruptors’ on the Horizon

For now, the biomass (and biogas) power industry is also counting on the proliferation of distributed generation. “There’s a large opportunity for biomass to contribute to a 100% renewable future, and it lends itself extremely well to distributed power generation at industrial/agricultural sites, especially on a microgrid basis combined with other renewables. I expect this approach to be a significant path forward in California. Concentric Power is actively working on several such projects now,” Brian Curtis, CEO and founder of Concentric Power, told POWER in September.

The projected electric vehicle surge could also be a boon for the industry, though that depends heavily on EPA action to include renewable electricity in the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). Congress created the standard in 2005 and expanded it in 2007 to approve participation of electricity produced by certain types of biomass, biogas, and the biogenic portion of municipal solid waste. But, as 111 biomass and biogas entities pointed out in a strongly worded letter sent to the agency on September 6, 2018, the EPA has been dragging its feet for four years on processing applications from power producers seeking renewable identification numbers, which are credits used for compliance and are the “currency” of the RFS program. If permitted to participate in the program, the baseload power–delivering entities, which lamented they have been “left behind by federal policies favoring other technologies at our expense,” would be classified in the cellulosic fuel (D3) category, where the EPA has fallen short of targets.

“Some of us generate power using methane from landfills, digesters and waste treatment plants; others utilize forest residues and other biogenic fuels, including the biogenic portion of municipal solid waste (MSW), that are combusted to make renewable electricity,” the letter says. “By whatever mechanism biomass and biogas electricity is produced, when our energy is used as transportation fuel, it qualifies as an RFS fuel, and we are entitled, by law, to participate in the RFS program.” ■

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor.

The post U.S. Biomass Power, Dampened by Market Forces, Fights to Stay Ablaze appeared first on POWER Magazine.