The War on Drugs Is Inseparable from US Imperialism

In Baltimore, a young black man is sent to prison for felony cannabis possession. In Glasgow, a council flat door is kicked in by the drugs squad. In Afghanistan, a field of poppies is incinerated from the air. In Mexico, police corrupted by drug cartels are implicated in disappearances and massacres.

The War on Drugs is generally presented as a global phenomenon. Each country has its own drug laws and enforces them as they see fit. Despite small regional differences, the world – we are told – has always been united in addressing the dangers of illicit drug use through law enforcement.

This is a lie.

When one traces back the history of what we now call the War on Drugs, one discovers it has a very specific origin: the United States. The global development of the drug war is inseparable from the development of US imperialism, and indeed, is a direct outgrowth of that imperialism.

Prior to the 19th century, drugs now illegal were widely used across the world. Remedies derived from opium and cannabis were used for pain relief, and less widely for “recreation”. Queen Victoria herself was fond of both opium and cannabis, before being introduced to cocaine later in life.

Then came the American railroads.

Thousands of Chinese workers came to America during the mid-1800s to build the Central Pacific Railroad. Once the track was complete, however, they immediately became regarded as a threat to white American workers. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the only US law to ever successfully ban immigration solely on the basis of race.

One method of stirring up anti-Chinese hatred was to attack the practice of opium smoking. No matter that morphine and laudanum were popular as a medicine throughout the US, Chinese opium was seen as a threat to American Christian morality, and particularly to American Christian women.

By 1881, as the Exclusion Act was being debated in Congress, reports began flooding out of San Francisco of opium dens where “white women and Chinamen sit side by side under the effects of this drug – a humiliating sight to anyone with anything left of manhood”.

Newspaper editorials thundered that the Chinese opium menace must be wiped out lest it “decimate our youth, emasculate the coming generation, if not completely destroy the population of our coast”, and that for white Americans, smoking opium was “not at all consistent with their duties as Capitalists or Christians”.

Crucially, however, the first modern prohibition regime was not founded in America itself, but in its first overseas colony. In 1898, America conquered the Philippines in the Spanish–American War. Charles H Brent, the openly racist Episcopal bishop of the Philippines, despised opium users, and appealed to President Roosevelt to ban this “evil and immoral” habit. By 1905, Brent had succeeded in installing the first American prohibition regime – not in the US itself, but in the Philippines.

Unsurprisingly, the ban failed. Bishop Brent decided that continued opium use must be the fault of the booming trade in China, and wrote again to President Roosevelt, urging that the United States had a duty to “promote some movement that would gather in its embrace representatives from all countries where the traffic and use of opium is a matter of moment”. The idea of international control of the drug trade had been born.

In the American debate, drug addiction had been framed as an infection and contamination of white America by foreign influences. Now, that vision was internationalised. To protect white American moral purity, the supply of drugs from overseas had to be curtailed at their source. As the campaigner Richard P Hobson had it, “like the invasions and plagues of history, the scourge of narcotic drug addiction came out of Asia”.

In 1909, America succeeded in convening the first International Commission on Opium in Shanghai. Representing the US were Bishop Brent and the doctor Hamilton Wright, who was to become a major force in the American prohibitionist movement. For the next century, almost every major international conference and commission on drug control was formed through American pressure and influence.

Interestingly, despite what we are told about the “special relationship”, the country that offered the most consistent and organised resistance to the American drive towards drugs prohibition was the United Kingdom. Time and again, Great Britain diplomatically frustrated American attempts to impose prohibition regimes and establish international protocols.

This was partly because the British were themselves operating lucrative opium monopolies in their own overseas colonies, but also because they resented “overtones of high-mindedness and superior virtue”. Britain had its own system of dealing with drug addiction – treating it as a medical rather than a law enforcement issue – and, for a long time, resisted the moralising hysteria of the American approach.

But it was difficult for the US to push the prohibition of drugs on the rest of the world while not enforcing it itself. Wright began spearheading a fresh campaign for full drug prohibition within the US – once again built almost entirely on racial prejudice.

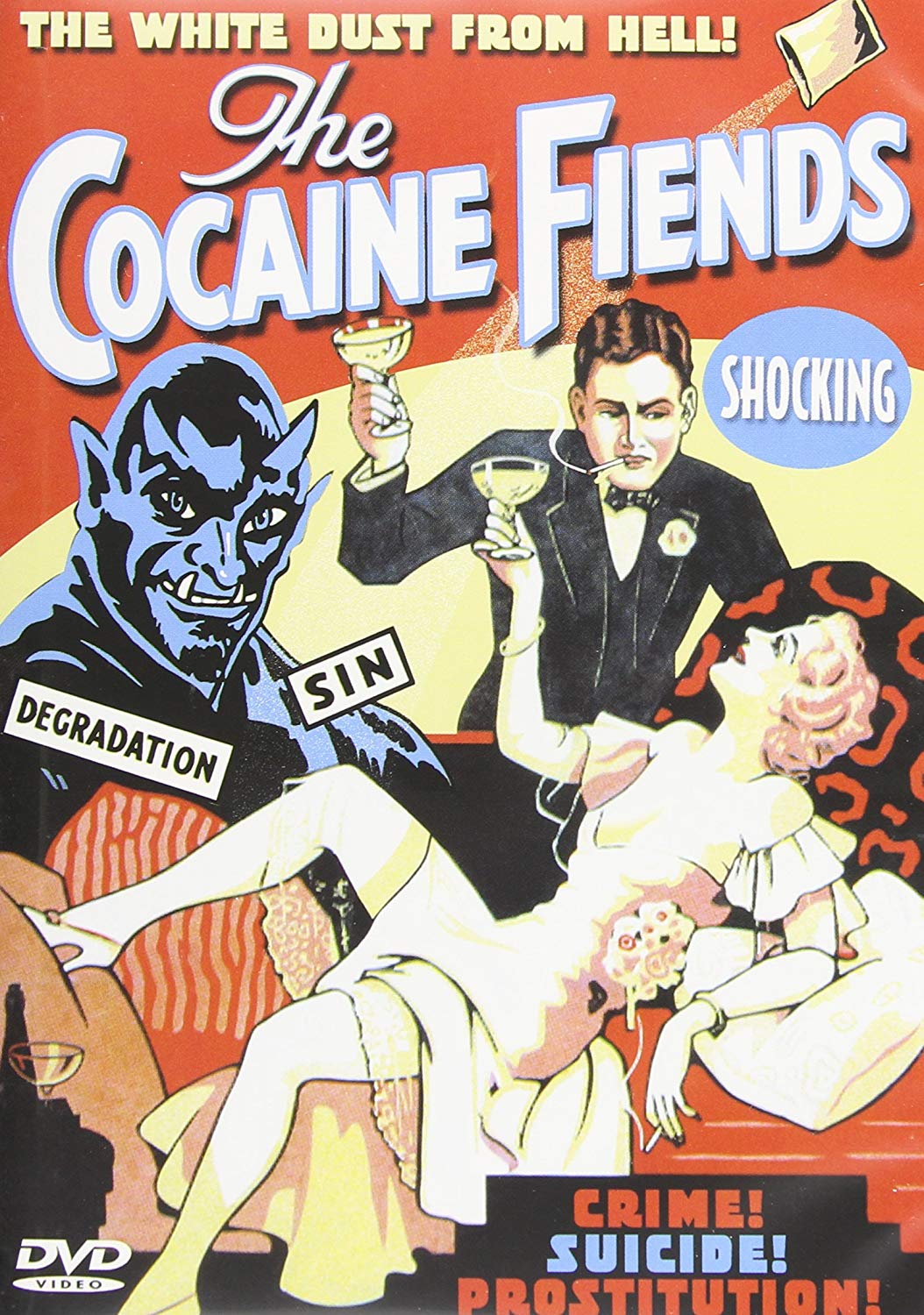

But this time, a new drug had emerged to capture America’s fevered imagination, with a fresh racial minority to use it to persecute. The drug was cocaine, and the minority African-Americans. In 1910, Wright submitted a report to the Senate stating that “this new vice, the cocaine vice … has been a potent incentive in driving the humbler negroes all over the country to abnormal crimes”.

There followed an explosion of headlines linking black people to cocaine use and criminality. The New York Times ran a typical story under the headline “NEGRO COCAINE FIENDS – NEW SOUTHERN MENACE”. The story tells of “a hitherto inoffensive negro” who had reportedly taken cocaine and been sent into a frenzy. The local police chief was forced to shoot him several times to bring him down. Cocaine, it was implied, was turning black men into superhuman brutes. As the medical officer quoted in the article put it, “the cocaine nigger sure is hard to kill”.

This hysteria resulted in the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, instituting the prohibition of drugs across the United States. Over the next 50 years, America would aggressively seek to internationalise its form of prohibition across the world.

Harry J Anslinger was appointed head of the US Federal Bureau of Narcotics in 1930. Alcohol prohibition was about to be repealed, and this tiny department must have seemed like a dead-end posting. But Anslinger embarked on a campaign of political and media manipulation that was to build drug prohibition into a key plank of both US domestic and foreign policy. He was to remain head of the FBN for 32 years, serving under five presidents and holding his office longer than any other senior civil servant except Herbert Hoover.

Anslinger was, in many ways, the architect of the modern War on Drugs – and the archetype of the American model of the moralising drug warrior. Anslinger was ruthless in his crusade, often stooping to methods that were unethical and, at times, actually illegal – particularly in the monitoring and persecution of artists, scientists and intellectuals he saw as a threat.

He was also a race baiter. In order to whip up hysteria in the press, Anslinger incessantly played on racial fear and prejudice, linking cannabis to Hispanic people, cocaine to African-Americans and heroin to the Chinese.

Chinese people, he warned, had “a liking for the charms of Caucasian girls”, using opium to force them into “unspeakable sexual depravity”. The increase in drug addiction, he insisted, was “practically 100 percent among negro people”, who would party with white women, “getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution. Result: pregnancy.”

Anslinger was not content to simply wage his crusade within the US. Throughout the 1930s he lobbied the US government to pressure the rest of the world to adopt a prohibitionist approach.

Then came the Second World War. Every country in the world emerged from the war significantly poorer, save one: the United States. Anslinger and his underlings lost no time in leveraging America’s newfound hegemony to force the other nations of the UN towards a prohibition model. They ensured that versions of the Harrison Act were written into the laws of the occupied Axis powers, and Anslinger had himself been appointed as the US representative to the Commission on Narcotic Drugs of the newly formed United Nations.

Every aspect of international relations, from military protection to trade deals to aid programmes, became a carrot or a stick to coerce other states to adopt the American way. Charles Siragusa, a high-ranking FBN agent, laid out these bullying tactics explicitly: “most of the time … I found that a casual mention of the possibility of shutting off our foreign aid programmes, dropped to the proper quarters, brought grudging permission for our operations almost immediately”.

Other countries were absolutely aware of this stitch-up and resented being forced to adopt American norms in order to satisfy racial arguments internal to the US. The British delegate to the CND complained that, had it not been “for the white drug problem in the USA”, other nations might have been left alone to pursue their own drug policies. Another UK representative expressed his frustration that at the CND, “the Chairman Anslinger … continually confused his position as Chairman and as US representative”.

From the end of the War in 1945, it took 16 years of American behind-the-scenes bullying, but eventually Bishop Brent’s dream of a blanket international ban on illicit drugs was realised. The 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was passed, intended to bring the confusing tangle of all previous drug treaties and conventions into line. This was the result of a US-drafted, and US-sponsored, resolution. It was an American policy, serving American interests – and the hallmarks of crusading American prohibitionism are threaded through its core.

The 1961 Convention is the only convention in the history of the UN to use the word “evil”, stating that “addiction to narcotic drugs constitutes a serious evil for the individual and is fraught with social and economic danger to mankind”.

Torture, apartheid and nuclear war are not described in these terms. Genocide is referred to in UN documents as an “odious scourge” or “barbarous acts”, but never as actually “evil”. That the UN, founded in the ashes of world war and the Holocaust, finds drug addiction the only phenomenon worthy of this word is a testament to just how heavily American moralising pressure was brought to bear.

The Single Convention laid out the international standard of placing drugs in different “Schedules” to determine their levels of danger, the punishments for trading them and their potential benefits to medicine and science. This Convention forms the basis for almost every individual country’s drug legislation. When other nations have threatened to deviate from the American model, the automatic sanctions written into the Single Convention are what keeps them in line.

A full inventory of how the United States has fully militarised the drug war around the world since the signing of the Single Convention in 1961 would take several books to explore. From sponsoring death squads in Latin America, to the DEA undertaking Special Forces-style missions in Afghanistan, to the old fashioned method of making eligibility for US foreign aid and preferred trade status based on cooperation with drug eradication and interdiction activities, the War on Drugs has consistently functioned as an arm of US military and economic hegemony.

Governments around the world – even that of Britain, which once resisted the prohibition approach and offered an alternative model – claim that it is right that they continue to “fight the war on drugs“. When they say this, one should never forget they are enacting an American policy that was forced on the rest of the world. A policy, moreover, derived from some of the ugliest and most shameful threads in US history itself. The War on Drugs is not a global conflict – it is an American conflict that has become globalised. We should all examine its failures and think twice about continuing to fight it.

This article contains extracts from the book Drug Wars, published by Ebury Press.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.