George Jung, the Inspiration Behind ‘Blow,’ Says Prison Saved His Life

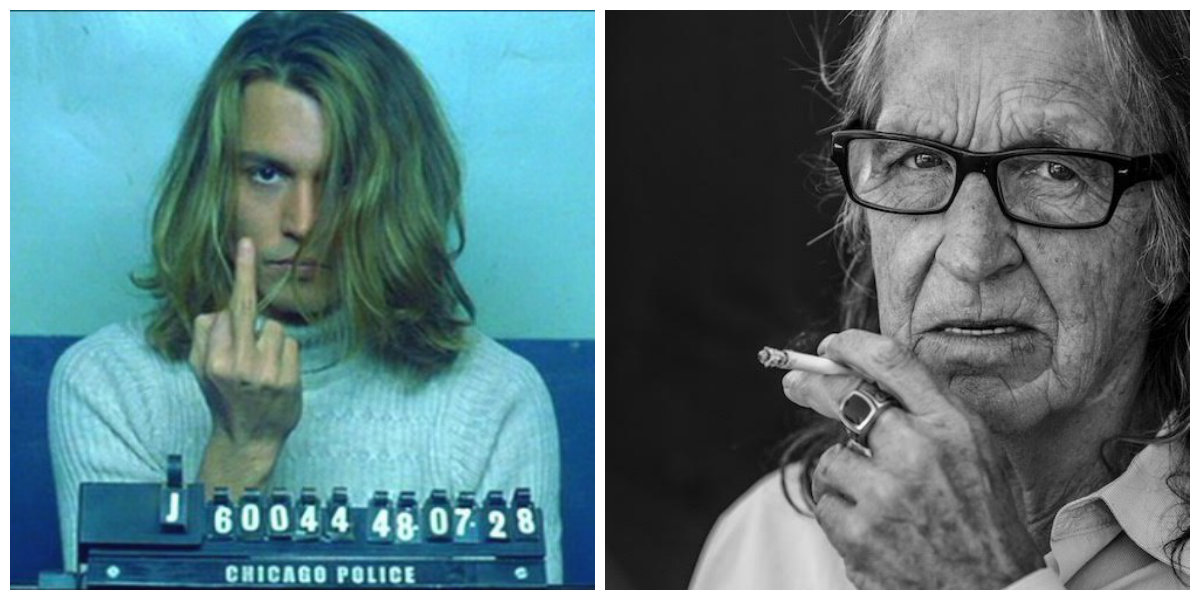

I first heard about George Jung in the Federal Bureau of Prison’s in the late 1990s. He was in the feds serving his own 22 year sentence, parallel to mine, and the book about his cocaine escapades with Pablo Escobar, Blow: How a Small-Town Boy Made $100 Million With the Medellin Cocaine Cartel and Lost It All, was making the rounds on the compound. By the time the movie of the same name, starring Johnny Depp as Jung, came out in 2001, Boston George was already a legend behind the fences. An integral piece of the cocaine explosion in this country, the man known as El Americano, had become an icon in pop culture lore.

Despite a recent setback and return to jail for a technical violation on his federal probation—he was giving a speech in San Diego without travel permission from his probation officer—George is back out in the world and ready to celebrate his 76th birthday, on August 6. On that day, at the TCL Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles, the theater is doing a special screening of the classic movie in honor of George and the late director of the film, Ted Demme. VICE talked to Jung to find out if he ever thought he would make it to 76, what the special screening means to him, what he remembers most about Pablo Escobar, and what’s up with the new docu-series he’s been filming.

Happy birthday George, how does it feel to turn 76? When you were younger, did you ever think that you would make it to this age?

I don’t think anybody, when they’re younger, ever thinks they’ll make it. But hell, I lived a pretty adventurous, dangerous life. You’re kind of a fatalist when you’re playing that game, living outside the law. I didn’t think I’d get to 76. I hate to say this, but if I didn’t go to prison for 20 years, I probably wouldn’t have made it to 76. I feel like a teenager sometimes when I’m hanging around the beach looking at the girls. But at my age looking at the girls is kind of like having a Ferrari with no engine in it. Getting old is not fun. Your body starts to break dow. I felt really damn good when I was 74, but now it’s breaking down a little bit. I’m one of those guys that have to hold on to the railing coming down or going up the steps.

Blow came out 17 years ago while you were in prison. Now you’re going to see it at the TCL Chinese Theatre in LA on your birthday. What does the movie mean to you now?

When they came to me with the proposal to make the movie, I agreed to it because I was in jail, and I needed the money. But I didn’t figure it’d go ballistic. When I got out of prison people told me how they loved the movie. Some people watched it a hundred times. I think to myself, “Dear God. I’ve never even watched the whole movie.” The director [Ted Demme] died a couple of months after the movie was made. This party is not only my birthday party, it’s in honor of Ted.

He was really good to me. He was a great guy, and the sad thing about it is he never got to know that the movie is a cult classic, it’s incredible. People come up to me all over the place and talk like tthey’ve known me my whole life. It was kind of annoying in the beginning, but when you get hit over the head with a stick enough times you kind of get used to it. And Ted told me, “Very few people have their own time machine. I’ve built one for you.”

What do you remember most about Ted? What sticks out in your mind when you think about him?

Him and I became really close friends. Jail is a pretty lonely place, really. He would come to visit even when he didn’t have to come visit. He was in constant contact with me on the phone. He looked after my daughter for a while, and I said, “Give her a job in the movies.” And he said, “I can make her an Assistant Director.” That was the best thing I could ever do for her. My father couldn’t do anything like that for me. Ted has a son, Dexter Demme, which is a great name, isn’t it? Dexter Demme. He’s like 19 now. He never saw his dad. He never knew his dad. I look forward to telling him about my relationship with his dad. I think that’ll be pretty special.

You recently went in for a technical violation of your parole. Are you still on paper? Are you out of prison for good now? Or, technically, do they still have you on the leash?

I’m still on a leash, but in September or October I’m going back in front of the judge, and the lawyer tells me that the judge will let me go. They really don’t need a 76 year old guy, with a pace maker, for Christ’s sake, to watch any longer. I really don’t break the law. I broke the law when I smuggled. Other than that, I never got arrested for anything.

I think they have bigger worries than looking to see what an old man is doing every day. The first probation officer I had was a woman. Her and I didn’t get along. The best thing that happened was them sending me to the county jail, and then the halfway house. I was able to transfer down to the San Diego area. I love San Diego, but it costs a fortune to live here. I’d like to move down to Mexico.

Looking back and reflecting on your life, what have you learned the most about yourself?

The judge, when he sentenced me, called me into his chambers. He said, “You know, I’m going to sentence you today. I want to ask you a question that’s been bothering me since the case came up to me.” He continued, “When you were 32 years old, you had a hundred million dollars (which is like a billion today) and nobody knew who you were. Why didn’t you just go away and take the money? Why didn’t you just leave?”

When I first started this smuggling business my dream was to get a million dollars, buy a sail boat, and take off to Tahiti. Then I got the million dollars. A million dollars in hundred dollar bills weighs 20.2 pounds. You can put it in a little camera case. I realized down the line that it wasn’t about the money. I was a thrill junky. I was addicted to the thrill of it.

When you first met Carlos Lehder in Danbury prison in 1974 did you ever think it would turn into all this? I’m not just talking about the money, but the whole pop culture phenomenon that you’ve become?

I had no idea. I was a marijuana smuggler. We were selling marijuana in Massachusetts to my old high school buddies that were going to college in that area. It was a lot of work dragging that stuff back and forth across the country in an airplane, across the border. Then I walked into a cell in Danbury, Connecticut and told him my story about the airplanes and he said, “Do you know anything about cocaine?” I said, “No, tell me.” He said, “Well, in Colombia, it costs $3,000 a kilo.” I said, “How much in the United States?” He said, $60,000. Then the lights went on and started blinking.

What do you think Johnny Depp’s portrayal of you?

Incredible. When he first came to see me, Ted Demme said, “Now, we’ve got Johnny Depp.” They were having trouble getting people. [First] it was Sean Penn. Even Tom Cruise was mentioned in this, and Val Kilmer. They were basically tied up and couldn’t do it. It seemed like they weren’t going to make it all, but Ted said, “I got Johnny Depp. You know, 21 Jump Street.” I said, “What the hell is that?” He said, “Well, how about Edward Scissorhands?” I said, “What was that?” This doesn’t sound too promising.

He came up to see me for the first time and he looked all disheveled. He said, “I was up all night in Greenwich Village trying to think about something to bring you.” I said, “Well, what did you bring me?” He pulled out of his pocket the book, On the Road, by Jack Kerouac. He said, “This is my Bible. I carry this everywhere. I worship this book.” I had read it in high school, and it influenced me also to go on the road and go to California. But I had no idea when I went to California that I was going to be a smuggler.

What do you remember most about Pablo Escobar?

When I went down to see him, I didn’t know who he was. I had been smuggling. I had been in the mountains of Mexico with the Indians and the bandits and the whole damn thing. The name meant nothing to me. But after a while, I began to see a really dark side. All that terrorist [stuff]. I wasn’t in the business for that. I was in the business for the money and the thrill of it. When it became violent and evil, I didn’t really want to play any longer. I told him, “You’ve got so much money. Why don’t you just take your family and go somewhere where nobody knows who you are and live like a king the rest of your life?” He looked at me and he said, “I will die here.” I just turned and walked away. I mean, there wasn’t anything to else to say.

You have a new docu-series coming out, tell us about that.

It’s with a young lady, a wonderful kid. Her name is Georgette Angelos, with her partner Chris. It’s called Boston George docu-series. I’ve been doing it almost a year and a half with her. She’s taken me on kind of time trip.There were good times and bad things. She [got] my old high school teammates out on the football field. I haven’t seen them in years. When we were driving there I thought, “These guys are never going to show up to see me.” I showed up at the field and what’s left of them, they were all there. I ran up and caught a pass. I was thinking, “Jesus, I hope I don’t miss this one.” But, the best part about that was that I wasn’t Boston George to those guys. They just knew me as George.

Has all the money and the fame been worth all the time that you spent in prison?

You can’t equate it like that. You can’t change the past. My hope has just been to live in the moment and the future. The best part about being out is being able to get up in the morning and make your own coffee, open the door, and walk outside. That’s wonderful to me. You can’t buy back regrets for wasted energy. I’m constantly asked that, if I have any regrets. Regrets are a foolish pastime. I live for now and tomorrow.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.