Working at a National Park Teaches You Confidence and Perseverance

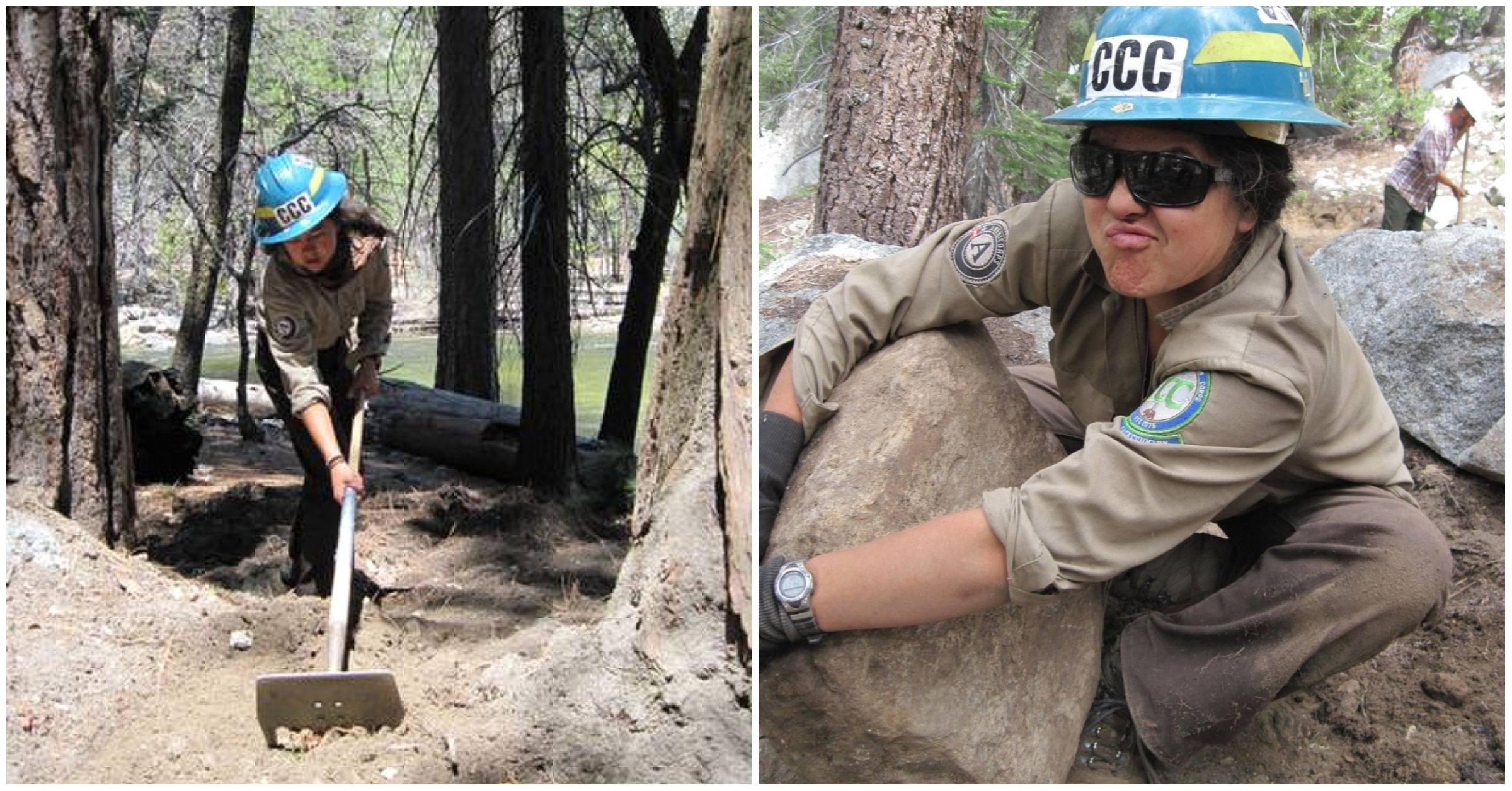

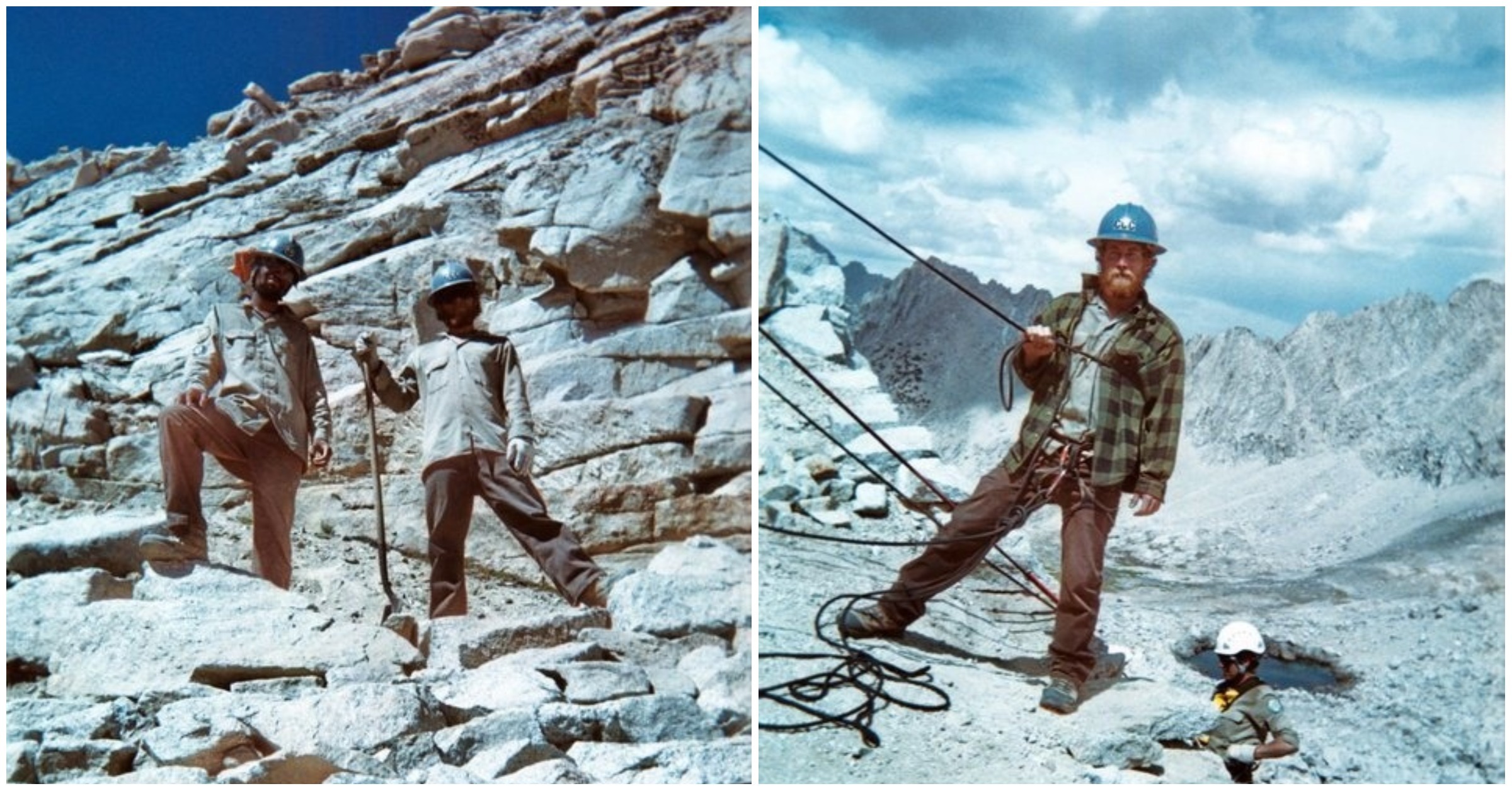

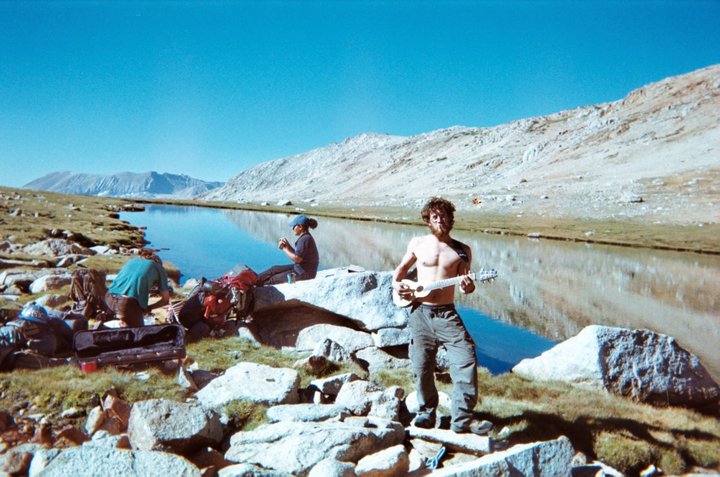

In 2010, I was accepted into the Backcountry Trails Program, a joint project between the California Conservation Corps and Americorps that takes gung-ho (and/or at-risk) young applicants and throws them up into the mountains with hand tools.

But back then, at 19, I was still thoroughly suburban. The longest hikes I’d done were a few miles at sea level. The only camping I’d done was at drive-up sites with picnic tables. And, aside from shoveling horse shit during my brief stint as a stablehand, the closest I’d come to any sort of manual labor was mopping floors and stocking shelves.

No prior experience was required, so I thought, How hard could it be? I found out.

It Isn’t Comfortable

It’s still dark when you wriggle your battered, crusty meat sack out of your frozen sleeping bag.

Every morning, among other warm-ups, you’ll want to do a thousand crunches. Not to cultivate discipline or machismo—it’s functional. If you can’t bust out a quick thou, you’re not equipped to schlep your tools on the morning commute, let alone use them throughout the workday.

And for me, the commute was the worst part. An adolescence at sea level coddled my respiratory system. Suddenly, I had to move fast as I could with a pack and tools—shovels, McLeod’s, loppers, Pulaskis, sledgehammers, 20-pound rock bars, grip hoists—uphill, nonstop, for miles.

Our crew ended up in Center Basin, working at elevations exceeding 13,000 feet. We were the highest-elevation trail crew in the country that year. Throwing up and fainting were possibilities on any given morning, but as one of the slowest hikers on our crew, I couldn’t afford to slow down. (We called it “hiking,” but some days it was more like handicap-weighted speed-mountaineering.)

Then began the actual workday. With the exception of a chainsaw we judiciously applied to clear fallen trees from the trail, we used hand tools for everything.

To the tune of snow, heat, river crossings, and mosquitoes, we turned big rocks into little rocks into littler rocks. We did this to make a foundation of several feet of “crush” hidden underneath dirt trails to prevent overgrowth.

Small talk during the workday largely centered around boot rot. We mourned the loss of toenails, but losing fingernails was a relief—finally, those blackened blood blisters underneath would depressurize.

You’ll Learn a Lot

You’ll learn to fear lightning when you’re working above the timberline. You’ll learn drystone masonry and how to build rock walls and stairs without cement. The standards are high: If your work can’t be expected to withstand a century of continuous foot traffic and weather, it isn’t good enough.

On Forester Pass, I partnered with a guy to build a small section of wall, maybe eight feet wide. He’d covered every square inch of his exposed skin despite the heat, because the sun at that altitude had rendered his whole face an oozing second-degree burn.

Still, he was chipper: “We’ve got this, easy. Two days. Three tops.”

It took us several eight-hour days to find an eligible boulder while remaining careful not to send any rogues tumbling onto other crew members in the canyon below. Once we found one, it took days to move it uphill by hand with the aid of rock bars.

Doing this stuff, you’ll learn that granite weighs around 170 pounds per cubic foot. And sometimes, after a long saga of investing in the potential of a single rock, you’ll learn that the rock ultimately won’t fit and has to be scrapped for a new one. You’ll work a week, sometimes longer, for nothing. Or, one clumsy blow with a sledgehammer will chip off an inch more than intended. So, you’ll learn to start over.

Say Goodbye to Personal Hygiene

There are different schools of thought about the best thing to wipe one’s ass with in the mountains, in the absence of toilet paper. Many heated debates on the subject have been overheard by marmots, pikas, and cheeseburger birds across the Sierra Nevada. I’m decidedly in the dust-off-a-smooth-rock camp. Take it from me—leaves rip.

For a week, I sang the praises of using pine cones. Gentle jeffrey, as opposed to prickly ponderosa.

That skid-marked to a halt when I forgot to check one for tree sap. I spent a rather sordid afternoon with my multi-tool by the creek, my own bitter coprolalia punctuated by the laughter of the other women on the crew, who had come to spectate for lack of better entertainment.

You’ll find your own preferences. In the same way a person might inflate their lifestyle to match their income, working in the backcountry teaches you that you can deflate your expectations when it comes to creature comforts.

Going without soap for half a year, you’ll find that a few branches of sage, a handful of mugwort, or an orange peel passes for a makeshift loofah when you’re feeling fancy enough to care. Bathing in snowmelt, your standards of cleanliness will plummet. As long as you’ve scraped at the Three P’s—pits, pooper, pisser—and your feet haven’t swelled with the aforementioned boot rot, you’ll declare yourself adequately clean on any given day.

Protect Your Food

Every week or two, a “packer,” a cowboy hat donning park employee on horseback, leads a string of mules up and down the trails delivering provisions. You’ll develop a taste for cowboy coffee, crunchy like dirt, and beef stroganoff that makes you shit orange. On weekends away from base camp, you’ll eat from cans of beans with sticks you find on the ground.

Bears become as pervasive a pest as mosquitoes. You’ll have a fire going daily for burnable waste, and will tediously wash and bleach all un-burnable wrappers and trash to rid them of any smells that might entice a black bear into your camp.

Of course, lacking more sophisticated refrigeration than patches of shade, you’ll store your weekly allotments of meat in buried metal boxes covered with burlap sacks. You will regularly re-wet the sacks in the nearest creek, blotting the excess blood off the raw cuts daily to slow down spoilage.

This means that every night, one lucky member of the crew will be placed on bear watch near the stored food. They’ll have noise-making implements within arm’s reach—usually a pot and a spoon, or whatever else is handy.

In theory, the rest of the crew is supposed to wake up and join you in the event of a bear, but oftentimes this doesn’t happen. On one weekend outing, a group of us blearily joined in a midnight chorus of “BEAR! GET OUT OF HERE, BEAR!” with our faces pressed into our sleeping bags for several minutes before realizing that what had been taken for a bear was actually one of the bigger guys on crew getting up for a piss. No one else had bothered to look up.

But the worst part of bear watch isn’t the occasional-but-generally-theoretical incidence of having to chase one off. Instead, it’s the far-more-horrifying prospect of waking up to a mosh pit of mice in your sleeping bag.

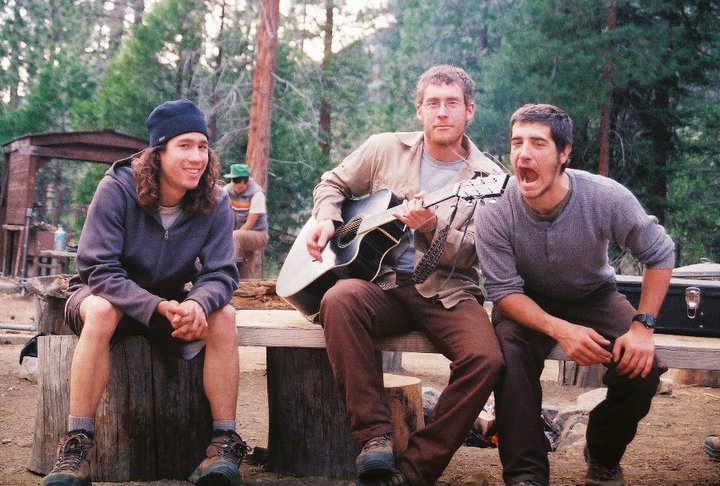

You’ll Crave Distractions

The hardest part is what you have to do with your mind.

In addition to food and replacement tools, the mustachioed packers brought us snail mail on their weekly visits. When your only mode of contact is mule-delivered letters, you might be surprised by who does and doesn’t bother to write. These deliveries often felt like our only concrete proof that the outside world still existed.

If you smoke cigarettes, importing enough to maintain a habit will prove a viable obsession. There’s only so much you can carry with you at the start of a season.

The restocking process looks like this: Write a letter to your most reliable friend, send it off on the next mule, pray that your letter will make it and that your friend will waste no time in shipping you a drum of Bugler. If your friend is fast, and no mules get spooked by rattlesnakes en route, the process will take a little over a month.

Meanwhile, the biggest fiends on your crew will scavenge in their tents or at fire pits for butts. When those run out, they’ll start rolling up random plant matter, torn up business cards, even sawdust—if not out of desperation for a placebo nicotine fix, then out of the desire for something to fixate on.

There isn’t anything to spend money on. No screens or speakers. Alcohol and drugs weren’t allowed on our crew, not that there’d be anywhere to get them. The selection of books is limited to what your crew bothers to carry. So over time, those of us who read cycled through a unified curriculum of Desert Solitaire, Ishmael, The Prophet, and the Tao Te Ching.

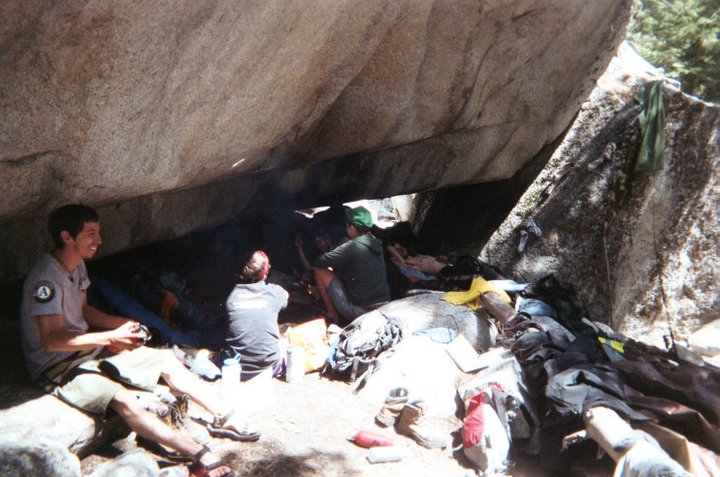

Without other distractions, it truly is Just You and These Fucking People. Fortunately, no one brought Lord of the Flies.

It’s Intimate

Unlike many crews who have fallen in love, created lifelong friendships, and host regular reunions, ours was not a symbiotic group. Despite there being only 17 of us, we branched off into paranoid alliances that morphed over time, bolstered against common enemies.

One long weekend, a group of us planned a steep hike up Mount Whitney and back, through Lake South America, Guitar Lake, and Kern Canyon. One girl had the brilliant idea to save on weight by packing only marshmallows and cereal, which she ate on the first morning. Like dominoes, most of us ran out of our food rations in order to keep her fed. On our final morning, we were down to a jelly bean each to fuel the last 15 miles back to base.

That is, except for one guy who had packed a surplus of food and made a show of hoarding it. Rather than deigning to share, he returned with 20 pounds of excess weight. Another guy, who was incontinent and hygienically challenged even by our standards, had a pack of extra sausages that literally reeked of shit. None of us were quite delirious enough to ask him to share.

We were such a misaligned band that even the odd bonding moments had a note of panicked desperation, which makes actual connection impossible. One weekend culminated in a regrettable truth or dare game that was never spoken of again. Nevertheless, it was intimacy, albeit feral.

Groups of us would visit the long-drop latrines and sit, three or four in a row, across the log stringers. We’d hold hands and cackle at whomever was the most squeamish as we shat together over a giant pit below. On more than one instance, I’d butt heads with someone for months, only to have that eventually give way to genuine fraternal affection and full-moon adventures scrambling up peaks or into dried-up tarns for Calvin and Hobbes-esque pontifications about life and how much we once despised each other.

You Could Die

Nothing will bring you closer to yourself than the realization that you’re alone and nowhere. Not in the middle of nowhere, but at the top of it, where your best chance of detection is a rescue helicopter. You’re cut off not only from the outside world, but from most man-made implements aside from what’s on your back. Far from any infrastructure more prominent than the trail you abandoned an hour ago in an attempted shortcut.

Nothing gives you a clearer picture of your limits than brushing up against the realization that, in this particular moment, perhaps for the first and maybe only time in your life, there is no safety net. You could be completely incapacitated by a single misstep.

It’s terrifying, bolstering, humbling, and addictive. You’ll clamber into Center Basin, a psychedelic fishbowl where there are no objects to offer any clues to scale or distance. It’s above the timberline, and its only features are grass, tarns, and bald peaks of talus and scree. Without anything to fix on, there’s no way to gauge that seemingly faraway rock.

The wind at your back will invite you to sprint across a meadow lousy with marmots and pikas—and you’ll encounter a rattlesnake or an ankle-breaker.

You’ll scramble a couple hundred feet up a sheer scree slope and then choke on your heart as your handhold crumbles and you begin to slide back down. It’ll take you four hours to get up, and half an hour to moonwalk down in your hiking boots over loose rock.

There were 16 fatalities between Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in 2017. You’ll feel more alive knowing that, in an instant, you could have been one of them.

You Won’t Understand Unless You Try It

A couple years after my time in Kings Canyon, I read Wild by Cheryl Strayed. I was excited to see what she’d have to say about the parts of the Pacific Crest Trail I’d helped maintain and build, and the wider areas I’d become so intimately familiar with. Nope.

She never made it to Forester Pass, nor most of the places I’d grown to love and hate. Due to snow, she bypassed the entire section by car. They’re high and remote enough that, unless perfectly favored by weather, timing, and brazenness, even several PCT thru-hikers never see them.

What did hit home for me, though, was her description of “retrospective fun” and the value of experiences that, at the time, are irredeemably shitty, but age well enough to turn into fond memories. This is what I’ve come to understand as self-definition.

When we were back in civilization, our crew separated instantly, desperate to mingle with crews from other parks, with faces familiar or new—with anyone, really. Years later, a half-hearted attempt was made to plan a reunion, but really, for all our feral intimacy, the camaraderie wasn’t there. I’ve met up with a few members of the crew. In most cases, we found that we’d become strangers. That, maybe, we’d been strangers the whole time.

There was a retrospective fun in all of it, though. My heart has a special tenderness for Junction Meadow, for Center Basin, for the moments where I found commonality with the others, even if it was fleeting, in private moments around fires or on secret excursions into corners of unspoiled wilderness.

The experience shattered my teenage hubris and spat it back at me. In place of that hubris grew a confidence that was deeper, fertilized by humility, and watered with sweat and angry tears.

Later on, I wandered into Yosemite with a map and a compass, a water filter, a large plastic sheet for rain cover in lieu of a tent, and little else. I didn’t emerge for three weeks.

My season in Kings Canyon acquainted me with my shadows, my neuroses, and my delusions in a way that allowed me to carry on into the unknown with a serenity unstirred even by the most stubborn apprehension.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Anna Mattinger on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.