The Conspiracy Behind ‘Three Identical Strangers’ Is Beyond Messed Up

The following article contains spoilers.

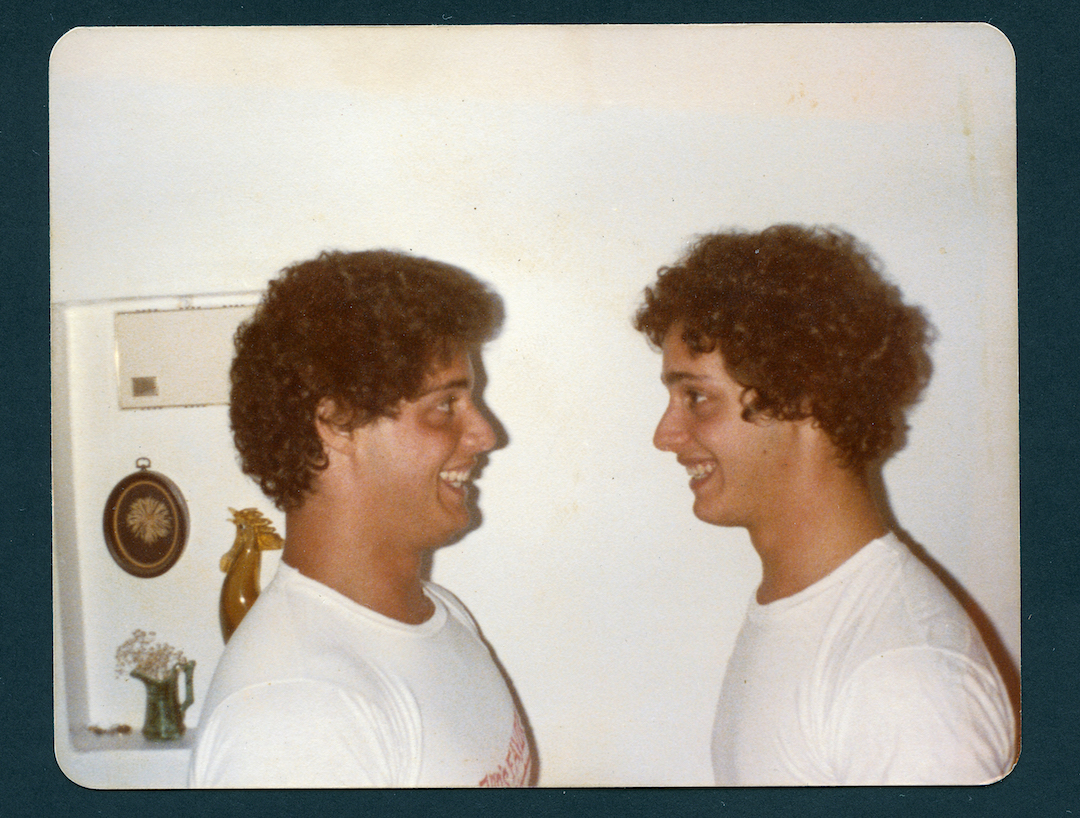

In the beginning, Three Identical Strangers plays like a feel-good movie. In the fall of 1980, Robert Shafran went off to college in upstate New York and found out he had a long-lost twin named Edward Galland. It’s some real Parent Trap shit. When local news picked up on the story, a third brother, David Kellman, came out of the woodwork, and for a while, the tale of identical triplets separated at birth fascinated the nation. The 19-year-olds became overnight sensations; they even had a cameo in the Madonna movie Desperately Seeking Susan.

But when the triplets’ families started asking questions, like why they were split up as babies and adopted out to three different families, none of whom were told their sons were triplets, things took a sinister turn. As the new documentary about their lives, Three Identical Strangers, elucidates, the brothers were part of an elaborate psychological experiment hatched in the 1960s to study the effects of nature versus nurture. Psychiatrists partnered with the Louise Wise Services adoption agency on a “Twin Study,” which involved splitting up identical twins and triplets, placing them in different home environments, and studying their development.

Kellman, Shafran, and Galland were three of their test subjects. No one, except the scientists who orchestrated the study, know how many other sets of twins and triplets may be out there, completely unaware they have long-lost identical siblings. The results of the study were never released. When the lead researcher, Dr. Peter Neubauer, died in 2008, all of his records were placed with Yale University and restricted until 2065, presumably long enough for anyone involved in the study to have died.

Three Identical Strangers charts a twisted tale of love and sorrow, weighing human cost against scientific progress. It explores the alchemy of three families brought together unexpectedly and plumbs the depths of the scientists’ deception. But it doesn’t—it can’t—answer all the brothers’ lingering questions. There’s still too many powerful people working too hard to keep the “Twin Study” under wraps.

VICE recently sat down with two of the triplets, Shafran and Kellman (Galland sadly took his own life in 1995), as well as director Tim Wardle about what it’s like sharing their story on the big screen and what they still wish they knew about the experiment they unwittingly participated in for the first part of their lives.

VICE: Why’d you want to tell your story now?

David Kellman: We believed the story should be told, but we were afraid of how it would be told. We didn’t want it to be exploited or sensationalistic.

Are you happy with how it turned out?

Kellman: Ecstatic. It exceeded our expectations on so many levels. We gave [Tim Wardle and the crew] as much as we could from the heart, and we didn’t know what they would do with it.

Robert Shafran: At the beginning of the movie I say, “I wouldn’t believe it if someone else was telling this story, but it’s true, every word of it.” After that, I’ve basically given my endorsement to something I haven’t seen. I just knew my story was true, and our story was true, but they really did come through. And they treated Eddy, who is not here to speak for himself, with a tremendous amount of sensitivity and respect.

Kellman: They really managed to bring him into the room.

I thought the way the film told Eddy’s story was really poignant. It underscored how much of a life-and-death situation this was.

Shafran: It is our lives. I feel like sometimes you don’t know how you’re injured until you see the results of the injury.

We were really caught up in just being together. People who were older and more mature than us asked if we were angry about being split up. This was before the experiment came out. But we were just happy we found each other. We were on a roller coaster of first times and fun. We went from house to house, and we were calling each of our parents, at least in the beginning, “Mom, Mom, Mom; and Dad, Dad, Dad.” And from behind—you saw it, our hair was huge—from behind, our parents would be calling us by the wrong names.

Kellman: In terms of being injured and not knowing it, it’s akin to a college football injury. All of a sudden, 20 years later, you can predict the weather, and it really aches. I think over time it really came out how it affected us, particularly Eddy.

Shafran: Also, we all had really tough adolescent years. Just growing up adopted can add another log to the fire, another dimension to the to the whole identity crisis of adolescence. We were all really emotionally disturbed kids. Sometimes you don’t realize what the answer is until you find it. It’s pretty hard to imagine the answer that we found.

When did the depths of the conspiracy become apparent?

Tim Wardle: Pretty early on. My first thought was, Why hasn’t anyone told this story before? Well, people have tried. There were three attempts, and every time, it got shut down. That made us sort of paranoid. As soon as I started finding out more about the study, the extent of it was pretty dark.

So who has the power to answer these questions?

Shafran: The Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services. They have begun a dialogue with us.

OK, is that a positive thing?

Shafran: We don’t know yet. There was a lot of back and forth before we got our records, some of which were 57 years old. They’re copies of documents, with black lines through most of these documents.

Right, at the end of the documentary, it says you accessed some of the sealed records. What did you learn?

Kellman: Besides being heavily redacted, they read almost like individual medical records. It doesn’t give us any hypothesis or updates to go on. We’re not scientists who can pick this apart.

Wardle: The Jewish Board has the power to release all the data and make it transparent, which hopefully they are going to do. There are psychiatrists alive and working in New York who worked on this study and could tell us more, but they wouldn’t talk to us. The two people who appear in the film were quite peripheral.

The stuff I’ve seen is a weird mix of hard data and Freudian psychobabble. I don’t know if it could ever be empirically used now. It’s just a total mess, this data, and they’ve collected so much. They’ve got 10,000 pages, and that’s just a fraction of what’s there.

Kellman: We’re hoping they will make some more sense of it for us—that’s one of the things we are hoping for. Not just for ourselves, but for the other people that were involved in this study. We feel some sort of reparations should be made, and we’re exploring the possibility, because these people caused a lot of injury to a lot of people.

What’s been the Jewish Board’s reaction to the film?

Shafran: They lawyered up.

Kellman: They’ve been dealing with us through a highly polished boutique medical malpractice attorney, which makes you ask yourself, Why would they need to go through these kinds of channels?

Wardle: There are really powerful people who don’t want this story to be told. That’s not an understatement at all.

Shafran: They put out a statement that said they were glad the movie was made. I don’t want to misquote them, but something about providing records in a transparent way, and here’s the weird part: they invite anyone who happens to be an identical twin, who knows they were separated at birth and secretly studied, to come and ask them for the records.

Could there still be twins and triplets out there who have no idea they were separated at birth?

Kellman: We were assured, to some degree, that the sets of twins who had not come forward had met through social media. They told us that they would be providing proof of that, although the proof would be redacted.

Has this experience coloured your trust in medical professionals?

Shafran: No, I can’t think of anybody else in modern times that has done anything like this. The other comparisons I can think of would be the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, where they let them all get syphilis and let it go untreated, and they died horrible deaths. Or the Agent Orange cases, where they just didn’t treat people.

When Lawrence Wright interviewed us for the New Yorker in 1995, I remember him asking how I felt about being an experiment. He gave me all the names [of the scientists] at once, and my response was, This is some effing Nazi shit.

That article was the genesis of a book he wrote about twins. We didn’t know that the first chapter was all about Josef Mengele, who experimented on twins during the Holocaust and did unspeakable things to them. And we were chapter two.

Kellman: We do know that the study was partially funded by the government.

Shafran: We were shown a document at some point, a grant application, and it said “longitudinal study on monozygotic twins reared apart.” Maybe you need a dictionary to look up “longitudinal” and “monozygotic.” But it said the money is for splitting up twins. Somebody knew that when they cut the check.

Another layer of this story is that because the records are sealed, no one can benefit from the data.

Wardle: You’re right. After the Mengele experiments in Auschwitz, there was a debate about whether the information should be used to save lives, or whether it was tainted and totally unethical. All this was done, and all these lives were wrecked, but nothing came of it.

It’s hard to watch the film and not be incredibly critical of this experiment and the scientists involved.

Wardle: I’m understanding, probably more than most people, about the experiment and the context in which it was done. I studied psychology at university, and in the 50s and 60s, it was kind of like the Wild Wild West. There was this paradigm shift where psychology was trying to establish itself as a legitimate science. All these experiments were going on, like the Milgram experiments and then later the Stanford prison experiment. They were doing things that today we consider totally unethical.

I’m interested in the gray areas of human behaviour. I’m not interested in evil people. I’m interested in good people doing bad things. Even with the historical context, [people involved in the Twin Study] did know it was wrong, because we’ve seen evidence that they approached other adoption agencies that said, No way, you can’t separate twins and triplets. That’s wrong.

Has your understanding of nature versus nurture evolved because of this project?

Wardle: Absolutely. I came in believing very strongly in nurture. I was shocked to discover just how influential DNA is. The idea that you could make decisions in your life for reasons that hinge on your ancestors—that you can’t fight and do unconsciously—it’s freaky.

But nurture is a check on that. As Larry Wright says in the film, we drift in the direction our genes push us. But ultimately, nurture can be a counterbalance. Just because we are drifting in one direction doesn’t mean were destined to be a priest, or a criminal, or whatever. But it is frightening how powerful genetics is, like way more powerful than I ever considered.

Here’s a funny thing: When the triplets showed up for our first meeting, they were wearing the same shoes. And they weren’t speaking to each other [at the time.] Even today, they’re wearing a similar polo shirt. That kind of stuff happened all the time, and it was very weird.

Do you think if you knew the truth—about being a triplet, being studied, being susceptible to mental illness—life would have been easier?

Shafran: I can’t go back, nobody can. You can’t undo this, but perhaps if we were together, the rough spots wouldn’t have been as tough. You don’t know what [your damage] is until you’ve found it, and then you find it, and it explains a lot.

Wardle: That is where it becomes completely unethical and you have no justification. When you have information about people that could literally be life or death and you don’t share it with them, you’ve crossed a massive red line. But people do it all the time. When you’re focused on a story or experiment it’s easy to lose track of the harm you’re inflicting. But this actually happened to these guys. It’s their life, not just a story.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Kara Weisenstein on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.