The Medics Who Get High On Their Own Supply

In 2015, Julien Warshafsky was found collapsed on the floor after mainlining the powerful opioid fentanyl. But he was no unfortunate street heroin user or dark web psychonaut. A junior doctor, Warshafsky had overdosed at work, five minutes after anaesthetising a patient at Medway Hospital in Kent.

In late June, an inquest revealed the popular doctor, who suffered from depression, had regularly injected leftover fentanyl for four years while working as a trainee anaesthetist in two hospitals between 2012 and 2015. Despite twice being caught stealing drugs and twice overdosing on the job – he also collapsed after injecting fentanyl at the Royal Surrey County Hospital in Guildford – Warshafsky was able to hoodwink his bosses into thinking his drug use was not a serious problem. In 2016, he died aged 31 from a fatal overdose while on sick leave without ever being treated for his addiction.

Young medics have a reputation for hard partying. But beneath the white coat of respectability, it gets darker; it seems there is a burden that comes with holding the keys to the nation’s medicine cabinet. With such privileged access to a cornucopia of potent highs, clinicians have a history of becoming addicted to the tools of their trade, although it’s always remained a taboo subject.

In her 2013 article “Dr Junkie“, psychiatrist Victoria Tischler said that “historical, cultural and professional factors have contributed to stigma and secrecy regarding addiction in the medical profession”. She said the most honest account of doctor addiction is a short story written by the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov, a former doctor, called Morphine, in which he documents the decline of a drug-stealing, addicted physician.

In 1909, not long after the sale of opiate preparations such as laudanum was banned in Britain, physician Oscar Jennings claimed that morphinism was responsible for one-fifth of all deaths in the medical profession. In 1924, German doctor Louis Lewin suggested that it was not just 40 percent of doctors, but also 10 percent of their wives, who were addicted to morphine.

In 1935, official government statistics estimated there to be 700 morphine “addicts” in Britain, of which a sixth were medical practitioners, the gatekeepers of narcotics. My grandad, Pat Daly, was one of these addicted doctors. A locum GP working in the Midlands and up north between the 1930s and 1950s, Pat was banned from prescribing, possessing and supplying controlled drugs under the Dangerous Drugs Act in 1937 after some of his supplies went missing. Pat and his wife Betty were addicted to cocaine and morphine, and she was reportedly one of the first people to be treated with methadone in Britain.

It wasn’t just your regular GPs getting high off their own supply. In the mid-1990s, it was discovered that while he was working as Margaret Thatcher’s senior adviser on NHS reform, Dr Clive Froggatt – a Tory-supporting GP from Cheltenham – was faking hundreds of diamorphine (pharmaceutical heroin) prescriptions to feed his secret habit.

Despite far stricter monitoring of controlled drugs since the conviction of GP Harold Shipman, who stockpiled the diamorphine he used to kill at least 250 patients using fake prescriptions, medics are still stealing drugs. In the last four years, the General Medical Council has investigated 89 doctors for drug offences, including theft and supply.

Hospitals are leaking drugs, too. In its most recent report into the management of controlled drugs within the healthcare system, the Care Quality Commission noted that feedback from its drug intelligence network had unearthed “an increase in incidents involving healthcare staff diverting controlled drugs for personal use”. Five NHS hospital trusts revealed that, between 2013 and 2017, they had investigated a total of 428 incidents involving missing or stolen opioid drugs, such as pharmaceutical heroin and fentanyl. At least 85 staff from hospital trusts in England were suspended for allegedly stealing drugs in 2013 and 2014.

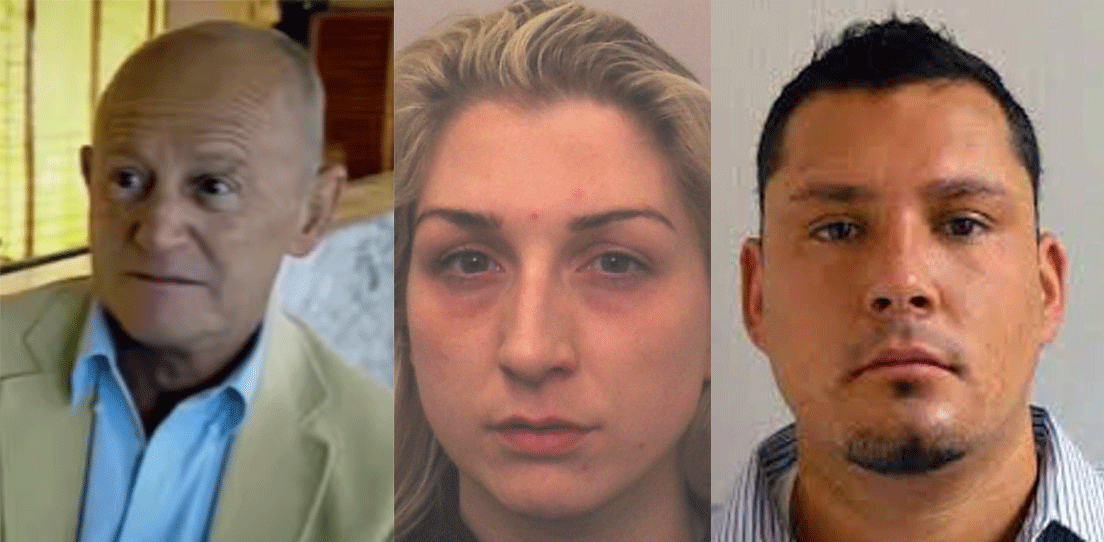

Very few of these cases bubble up into the public domain. But some do. In May, nurse Amie Heller was struck off after she was caught stealing large amounts of prescription opiates from the Royal Blackburn Hospital. She had sold the stolen drugs to friends in order to fund her own addiction to cocaine. In March, Kimberley Cooper received a suspended prison sentence for stealing morphine on 40 occasions while working as a nurse on a gynaecology ward at Lincoln County Hospital. The court heard that Cooper had used morphine to treat her own medical problems, but quickly became addicted, and began stealing just a month after starting the job.

In the US, the LA Times‘s “Dirty John” podcast highlighted how, as a nurse anaesthetist, conman John Meehan stole large amounts of opiates while working at hospitals in four states in the early 2000s. Meanwhile, former medical technician David Kwiatkowski was sentenced to 39 years in 2013 after he stole syringes of the painkiller fentanyl, injected himself and refilled them with saline. Instead of fentanyl, patients were injected with a mixture of saline and Kwiatkowski’s hepatitis C infected blood, causing an outbreak of the virus in New Hampshire.

Almost every day for two years, Tony (not his real name) stole drugs while working as a nurse in a Midlands hospital. Going into the job in the mid-2000s with a developing addiction to street heroin and crack, he told me that being surrounded by narcotics was part of the plan.

“I subconsciously knew I’d be around drugs before I embarked on my nursing career,” says Tony, now in his early-fifties. “When I started working on the ward, there were drugs available that I knew would help me when I felt a bit rough from the heroin. So I started taking valium and DF118s [dihydrocodeine] discreetly from the drugs trolley on the ward.

“My addiction was made easier as I was a nurse, for sure, as I had easy access to other drugs to supplement my habit. Later on, in my convoluted thinking, I decided I would use the hospital drugs to try a home detox from heroin. So I started stealing five days worth of intravenous diazepam, tramadol and some butterfly needles. I tried this a few times, but I’d just binge on the drugs. They’d rarely last longer than 48 hours. It was totally counter-productive.”

At the time, Tony was working on a cardiac ward, where lots of morphine was used for heart attack cases. “Patients were regularly prescribed 10mgs of morphine, but only given 5mg via a cannula. The rest would be in a syringe on the doctor’s tray for disposing, so I’d take it myself,” he says. “Morphine itself is not so strong, so this would need to be done more than once.”

This is exactly how plastic surgery specialist Samia Naz Siddiqui stole morphine on 200 occasions while working at York District Hospital in 2014. She took leftover morphine and injected it at the end of her shift, before being spotted by security guards, and was given a suspended prison sentence.

Tony did not get caught. “It was all so easy,” he says. “If my ward ran out of drugs I’d simply go to another ward and ask for them. I made it even easier for myself by volunteering to be the stock taker for my ward, so I ended up liaising directly with the pharmacy in the hospital, no questions asked. But my work became sloppy. I fell asleep during one-to-one care with a patient who had a stent put in. He pulled the emergency cord next to the bed when he saw me asleep, and I woke up as the crash team came hurtling into the patient’s room. That was the last day I worked as a nurse. My manager basically said something along the lines of, ‘I know something’s up, don’t bother coming back till you’re sorted,’ so I went on the sick for a long time, eventually quitting as my life spiralled out of control.”

Research shows that medics are no more likely to be addicted to drugs than the general population, even though they have some of the most stressful jobs. But there are risk factors such as depression and access to drugs that, when combined, make some clinicians far more likely to end up trapped in a cycle of stealing and addiction than others.

It’s no coincidence that the clinicians most likely to steal and become addicted to drugs are those who work most closely with them. Anaesthetists – those calming doctors who make jokes before ensuring you’re too out of it to realise your body is being cut up – are almost three times more likely to become addicted to drugs, end up in rehab and to die prematurely than other physicians. Over the last two years, the Association of Anaesthetists has become increasingly worried about the number of anecdotal and reported cases of suicide in anaesthetists and has set up an initiative to look at the issue. It’s a highly stressful profession, as the slightest error by an anaesthetist can result in a fatality, but the over-riding reason anaesthetists are more vulnerable to drug problems than other physicians is because the main tools of their job are extremely potent opioids.

To an anaesthetist, fentanyl is the equivalent of a plumber’s wrench, and they have unprecedented access to these drugs, more so than any other medical professional. They witness the effects these drugs have on patients on a daily basis, and it is these drugs to which some anaesthetists become addicted. Anaesthetists live and literally breathe powerful opioids. Some researchers have put forward the “exposure theory”, which suggests that airborne traces of opiates exhaled from patients’ mouths in the operating theatre can slowly sensitise anaesthetists and lead to them getting hooked. But the most likely theory is that it’s a cocktail of stress and access.

The Association of Anaesthetists, which represents the UK’s 11,000 anaesthetists, accepts there is a problem with drug abuse within the specialism. “Anaesthetists are more likely than other doctors to abuse narcotics as a drug of choice, to abuse drugs intravenously and to be addicted to more than one drug,” they write in a 2011 report. “The fact that anaesthetists have easy access to a wide range of psychoactive drugs may well influence the likelihood of trying them. Having become dependent, staying at work helps the addicted doctor to maintain his or her supply of drugs.”

Tales of drug theft and addiction have been part of the anaesthetist’s landscape for a while; it probably didn’t help that, up until the 1980s, it was customary for anaesthetists to sniff the drugs before using them on patients. A now-retired former anaesthetist told me he had been professionally involved in four cases of “bad behaviour” during his career.

“The extent of my involvement in the first was only that his death created a vacancy that allowed me to get into the speciality of anaesthetics in the first place,” he says. “He was an anaesthetic registrar who had a habit of using his car heater as a vaporiser for halothane, a then-new inhalational anaesthetic agent. He was found dead in his car, presumably having taken an accidental overdose.”

In the mid-1990s, a trainee anaesthetist was caught stealing morphine by chance. “After her apprehension, it was noted that she had multiple injection sites and she agreed that she had been mainlining for some months,” says the retired anaesthetist. The trainee agreed to have treatment and was transferred for further training in a facility where access to powerful drugs was not available. “There were two interesting things about the case: her husband apparently had not noticed, and whatever the weather or the theatre temperature, she had a habit of wearing a long theatre gown which covered the marks of her misbehaviour,” says the former anaesthetist. “This is why colleagues are now alert to the inappropriate wearing of long theatre gowns.”

The third case involved a trainee who didn’t get out of bed when he was on call as expected one morning. “Someone went to look for him and found him unconscious with evidence of mainlining propofol [an injectable anaesthetic agent] nearby. He too was advised to leave the [facility] and find a job with no access to powerful drugs, which he did.

“The last case involved a rolling stone who was appointed at a locum consultant level to a London teaching hospital. While working at a private hospital in London he was noticed by one of the theatre nurses squirting pethidine [a synthetic opioid] under his tongue. The nurse reported the misbehaviour and it turned out he used rather more pethidine per case than would have been expected, and he left the country. The nurse was very concerned about her own career for blowing the whistle, but was reassured by her manager. But I have to say that this all occurred about 15 years ago, and one hopes that whistleblowers do not now live in such fear.”

WATCH: Xanxiety – The UK’s Fake Xanax Epidemic

Part of the problem with medical professionals who become addicted to drugs, especially doctors, is that they hold a position of authority and respect. People trust them and may be intimidated by them. Staff and colleagues do not want to challenge them, thereby risk ruining their careers. So, in many cases, a blind eye is turned and their addictions can go unaddressed and have serious consequences for the individual or his patients.

This is what happened to Julien, says his father, Robin Warshafsky, a GP from Canada. Robin is convinced that his son died because his colleagues were too willing to swallow Julien’s side of the story.

“Julien was a high functioning performer, so colleagues trying to preserve his career, they cut him too much slack, which ended up killing him,” says Robin. “Everyone gets stressed and has existential woes, but what is different with doctors is the special access they have to drugs. They don’t have to go on the street, don’t have to pay, and they are good at protecting that access, so they function as best they can to protect it.”

Some doctors have barely needed to keep up the pretence. A court case in Devon in 2012 revealed how anaesthetist Dr Matthew Cornish managed to get away with stealing and taking hospital drugs at work for 15 years. This is despite Cornish’s behaviour being “desperate and beyond caring”, “out of control” and “chaotic”. He would often inject himself with diamorphine and fentanyl in the hospital car park before going into the operating theatre. By the time he was caught stealing drugs, his locker and home were littered with drug paraphernalia and his white coat was stained with blood from used syringes.

Addicted doctors are not just proficient at convincing colleagues they should be left alone. They are also experts at cheating themselves, says Robin. “They think they are all powerful and that they have better control over drugs than lay people because know all the facts. Once they have stolen and used drugs and fooled people successfully, they think they are in control. They can give all the right answers if they are investigated.”

For doctors and nurses who, for whatever reason, have the urge to escape into a drug-induced state, the medicine cabinet is close at hand. What’s more, it’s almost as if colleagues are actively not looking for signs of narcotic impropriety. As the retired anaesthetist tells me, “Considering the very large number of nurses and doctors who have ease of access to both opioids and other potential drugs of entertainment in the course of their work, it is surprising how few of these cases come to light. On balance, I would say that both the nursing and medical professions behave in a pretty responsible manner.”

With the issue of doctors stealing drugs now more out in the open, systems have been tightened up to prevent abuse. Drug cabinets are not as easily accessible now as they were a decade ago. Dr Liam Brennan, President of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, told me his organisation is well aware of the impacts on mental health felt by many trainee anaesthetists, including Julien Warshafsky. As a result, the RCA now holds face-to-face listening events, addresses the issue of drug addiction within new doctor induction packs and briefs senior doctors so they are better able to identify vulnerable colleagues.

But for those who do find a way of dipping into the nation’s drug supplies, help needs to be provided. As Clare Gerada, head of the Practitioner Health Programme for doctors with mental health problems, has warned: “We must allow doctors to become patients without the fear of sanctions or blame, and afford them the same compassion as they are expected to give their own patients.”

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.