Human Factors: How Do Stress and Fatigue Affect Safety?

Ergonomics—human-factors engineering—should be considered in all workplace improvement efforts. Feeling safe and staying clear of injuries can immensely contribute toward increased productivity by reducing the stress placed on personnel. Moreover, having the right tools and regular breaks during a workday can significantly reduce errors and increase efficiency, thus benefitting not only the individual but also the organization.

What is meant by human factors, and why are they important? One expert defined “human factors” as environmental, organizational, and job factors, and human and individual characteristics, which influence behavior at work in a way that can affect health and safety.

Every person is different, meaning that there are as many variables to a job as there are people. Each individual brings an assortment of skills and a unique personality to the workplace; therefore, each requires personalized support to maximize their capabilities. Ergonomics (the study of the ways in which working conditions can influence the effectiveness of a task being done) looks at both organizational and human aspects that could contribute to job performance. This includes everything from workplace culture to the optimum height of a desk and work equipment.

Workplace culture builds a foreground for safety, well-being, and performance, which is why ergonomics, or “human-factors engineering,” should not be excluded from improvement efforts. As part of a commitment to a safe environment, organizations should be accountable for educating their employees on possible work-influencing factors, such as fatigue and situational awareness, and making sure all necessary means have been exhausted to facilitate the most-effective workplace possible. Management must take a proactive stand on this, and listen to not only the numeric indicators, but also the human characteristics behind incidents.

In movies and on TV, we have seen examples of incidents being caused by human factors. In the TV program “Breaking Bad,” a plane crash was caused by a staff member being upset. In season two of the series, Donald Margolis was mourning over his daughter, which led to him giving the wrong instructions to a commercial airplane causing two planes to crash in mid-air. A Hollywood example, but an example nonetheless, of how human factors can have catastrophic consequences.

Clear and precise communication, regular retraining of work skills, and spreading awareness of human factors can reduce human errors and make workers more conscious of their surroundings. The focus of this article is the role the human mind plays in safety and how and why organizations should consider human factors in the workplace.

Psychology Behind Our Actions

Risk prevention is not limited to reacting to signals; we must also understand the reasons behind our reactions. Digging deeper into the human mind will help us comprehend how we learn and remember, thus allowing safety initiatives to adjust to these processes accordingly. It is extremely useful to understand what happens in our cognition when we absorb new information and observe the environment. Here is my attempt to briefly explain what goes on inside our crazy minds.

Sensation, Perception, and Response. Events in our environment are first processed through our senses, which “forward” information to our short-term sensory store that can hold new information for up to one second at a time. Sensation is not, however, equal to perception (the action of the brain determining the meaning of the sensory signal, the event). The way in which each of us “gives” a meaning to a sensation depends on our personal past experiences. There are a vast number of different perceptions different people can have of a single event when each individual brings a distinct background with differing experiences.

The second step after perception is response. Each individual sees and perceives information differently and is therefore likely to respond in a different way. If I urged you to think of all the possible perceptions of an event, then perhaps it might be even more relevant to think of all the likely responses of personnel. It is possible that there may be no response after perception, but the information is used for learning by using our working memory, from which the information can be further transmitted into our long-term memory.

Working Memory vs. Long-Term Memory. The difference between working memory and long-term memory is that working memory has a limited capacity and merely serves as a short-time memory storage for information that will be used promptly. From working memory, it is possible to transfer information into our long-term memory through learning and training.

Not all memories will be remembered, however. Interference, which refers to the input of a new piece of information too soon after another, can lead to information being “wiped out.” Interference can also cause the removal of old memory if the new memory is too similar to the old one. One of the more obvious reasons for losing old memory, or not remembering a new event, is our limited capacity to remember. A workplace example of a new piece of information taking over an old one could be a changed security code for a door.

Hence, from initial perception, our mind begins to find a way to respond to the experience. If we think of the human mind in this way, we might be able to better understand the reasoning behind our actions in the workplace in order to address those issues. A very relevant example, brought forward by Christopher D. Wickens et al. in the book Engineering Psychology and Human Performance, is that of decision-making. We all have to make decisions at work. This requires understanding a lot of new information while analyzing this on the basis of our old knowledge. In other words, we use our memory to fill in the “missing cues” of the situation. However, since our memory is prone to errors, we must be wary of this. It is suggested then that a good decision-maker is able to recognize the key information required before they successfully make the call.

Fatigue and Stress

There are other variables that might affect our ability to fully assess a situation, such as fatigue and stress (Figure 1). How much information are we actually able to absorb when the clock hits 5 p.m.? Or, how well would you be able to consider all relevant points if given 30 seconds to make a decision? Being a leader involves decision-making, and sometimes those decisions can impact hundreds or thousands of lives.

|

| 1. Stressed out. When a person’s to-do list is more like a too-much-to-do list, it can be overwhelming. Stress and fatigue are the result, and that can lead to errors. Courtesy: Pixabay/ kmicican |

When the captain of the Titanic decided to put on more speed, he relied on the current statistics and good weather. However, had he used his previous experience and knowledge to fill in the missing cues of short visibility and icebergs, the accident might have been prevented altogether. In such a big accident, panic also plays a role. Panic is a state of mind that can easily cloud our judgment when under pressure, which can lead to risky situations if we let emotion override our rational thinking.

Being tired at work is not something that should be taken lightly. EHS Today reported that 40% of U.S. workers suffer from fatigue. Fatigue does not only influence our performance, but also our safety. Tiredness affects our judgment and puts our health at risk. You might have heard of Miwa Sado, a Japanese political reporter who sadly passed away at the age of just 31 years after having worked 159 extra hours during her last month at work. There have been other fatalities in Japan caused by overwork (this cause of death even has its own name in the local language: “karoshi”). So, what is it that organizations should be doing?

Workplace Responsibilities

Organizations can improve their staff’s skill competency by organizing training so that it goes in line with peoples’ cognitive abilities. For example, by teaching one task at a time, without interruptions or other new information input, workers can better digest and acquire new information. Also, regular re-training helps personnel maintain high skill levels and keeps forgetfulness at bay.

Bridget Leathley addressed the issue of skill decay via Health and Safety at Work. Leathley brings forward the issue of skill decay in high-risk industries, and points out that despite training certificates’ expiry date, skill competency can significantly decrease before the set date. Especially when talking about safety certificates, it is a risky business to rely on acquired skills that are put in use only once in a blue moon.

Measuring fatigue and other human factors can be a more challenging task. However, companies can educate their employees about the risks involved in working long hours, and pass on non-technical skills to their employees—situational awareness, communication, and decision-making, for example. These tools make workers aware of their importance and enable them to work in a safe and efficient manner. An open work culture also contributes to nurturing a healthy workplace in which issues such as tiredness or stress can be raised without fear of dismissal or judgment. Staff should also have access to regular consultations with a nurse or a doctor.

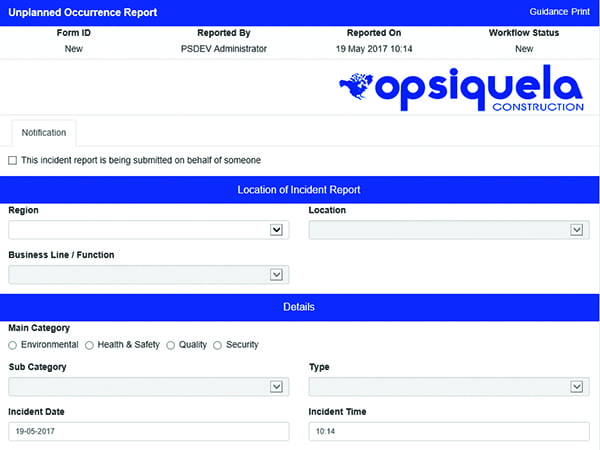

Tackling the common issue of fatigue is challenging, because its effects can vary from person to person. For those looking for advice, there are guides on how to implement a fatigue management plan. Also, tracking simple statistics such as man-hours worked and setting limits on overwork can help to regulate the phenomenon. Some tools, such as environmental, health, and safety software (Figure 2) that integrates with a human resources program, can be incredibly useful in calculating not only lagging but also leading indicators.

Although I have mainly focused on the human and individual characteristics of human factors, aspects such as workplace design should not be forgotten. To support the health and efficiency of staff, tools, workspaces, and workstations should be designed ergonomically. Also, noise and general disorganization should be reduced to a minimum. Human-factors engineering helps organizations to not only minimize human errors and maximize productivity, but also to improve their safety performance. When planning training, it is helpful to consider employees’ capacity to learn and remember. Understanding the human characteristics involved in each job and nourishing a healthy work culture can surprisingly, in our modern world of quantitative data-overload, be the key to a better performing workplace. ■

—Tytti Rekosuo is a digital marketing executive at Pro-Sapien (www.pro-sapien.com), a firm that provides tailored environmental, health, safety, and quality management software for organizations.

The post Human Factors: How Do Stress and Fatigue Affect Safety? appeared first on POWER Magazine.