Becoming My Own Half-Asian Man

“Becoming My Own Half-Asian Man” was originally published in Banana Magazine Issue 004. Banana Magazine is an annual print publication dedicated to contemporary Asian culture, striving to navigate through blurred Eastern and Western boundaries while creating a voice for the new generation of Asians. You can find more information at Banana-Mag.com and purchase a copy of the latest issue here, or follow them on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

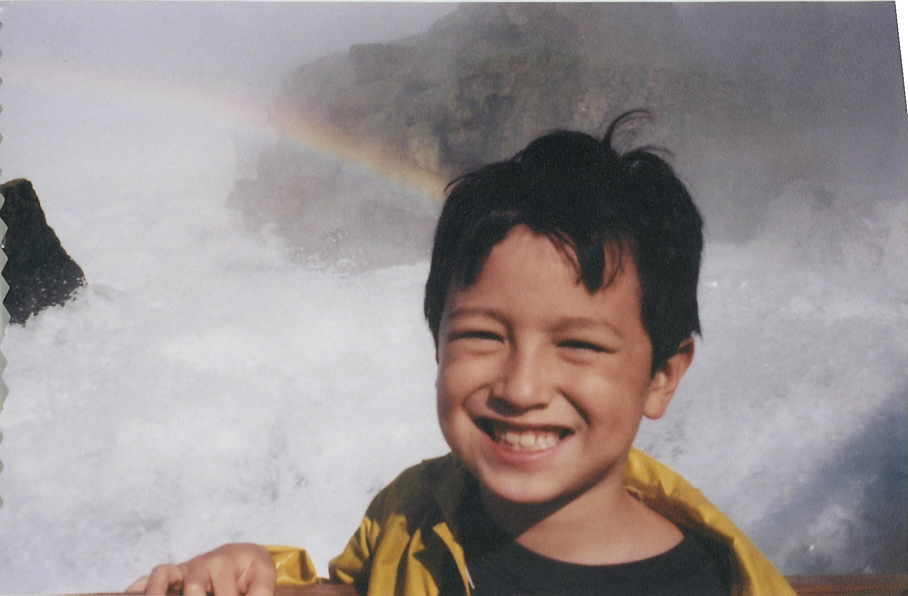

Until I was 12, I had no idea that I looked Asian.

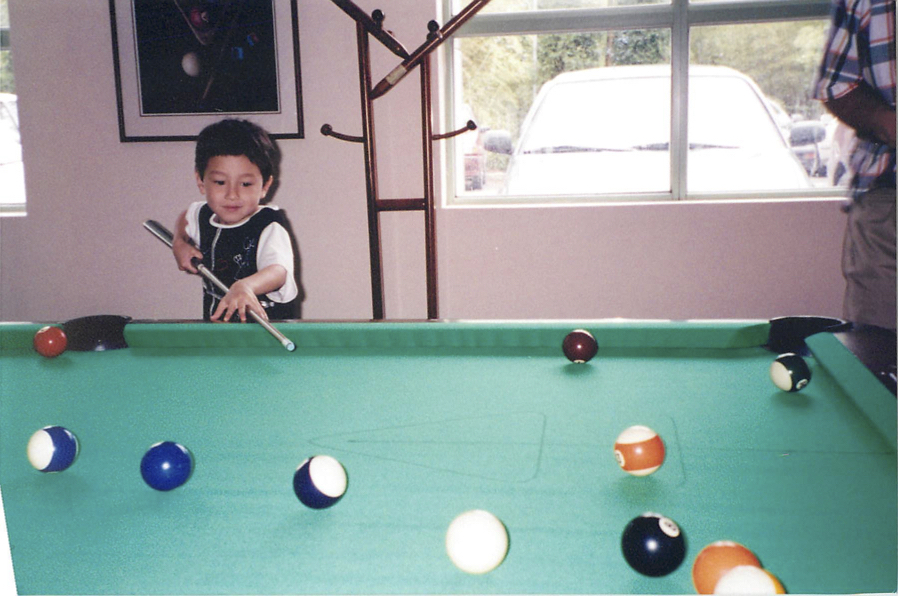

I knew my identities: Taiwanese, Jewish, Cleveland-Ohioan who spent weekends visiting grandparents in Youngstown and winters visiting cousins in Taipei. But on the West Side of Cleveland, where I was born and raised, everyone around me was white, so I assumed I wasn’t much different from them.

My dad, a religious everyguy who grew up in the inner city of Youngstown, shared my naïveté. He took me to synagogue four times a week, fed me corned beef and rye bread at Jewish delis, and teased me about looking like him, even though I didn’t. He didn’t warn me what I might face as an Asian boy in the middle of the country as the storm of adolescence approached.

It was Jews, in fact, who called me “chink” for the first time. I was in seventh grade at a religious Jewish retreat. A group of older white boys—who had been acting standoffish towards me the whole time, questioning if I was “really Jewish”—pounded on my door. They screamed, “Come out, you fucking chink!” And then they ran away, hollering and laughing.

I’m not even sure I had heard that word before. I definitely had never thought it applied to me. But I felt its power immediately—it knocked the wind out of me. My dad had warned me against anti-Semitism and raised me to revere Orthodox Judaism, and here those same Jews had just called me a fucking chink.

You go through childhood ensconced in illusions—that adults are Gods, that people will accept you, that you won’t be singled out for something you can’t control—and in a second, the protective cocoon is ripped open and you tumble onto the harsh landscape of an alien planet. I think for most minorities, there is a common experience of realizing that you are different—often when someone finally points it out. It could be the first time you’re called a racial slur, the first time some kid says “my daddy says this about your daddy,” the first time you’re told you can’t be a lawyer or the President.

Maybe if I had never been called “chink” I would have felt white forever. After all, the difference between my white friends and me is that they didn’t have to confront their race in childhood. But that was all over now. I had been identified, labeled, and excluded—by my own supposed people. I realized that society would not view me as white, so I wasn’t white.

When I returned to school, I viewed everything through the race filter. In a diverse middle school on the East Side of Cleveland, all I saw was self-segregation. The “popular kids” were white. The “nerds” were Asians. While my white friends had their first kisses, I worked up the nerve to tell my first crush that I liked her. She responded, “Ew, Zach, you’re weird-looking.”

It dawned on me that a lifetime of American media didn’t apply to me. I had assumed that I was just like any white guy in movies—I could be the protagonist, the ladies’ man, the punk, or even maybe the bookish Hebrew scholar from The Chosen, but that was all gone now. No, I was a “chink”: A trope of an Asian man, a character I knew little about but had internalized, like many other Americans, as an emasculated nerd. I remember sitting in the back of my dad’s car one night crying and shaking as I told him that “no girl will ever like me because I’m Chinese.”

Of course, that was far from the truth. I would eventually move to New York City for college and be overwhelmed by the amount of girls who thought my Asian features were attractive. The cultural paradigm shift that has occurred in the last few years has helped, too. I’m shocked at the amount of beautiful women who now say, “I don’t date white guys.”

But no one was around back then to tell me these things. My dad had no idea how to respond to my childhood crisis. Instead of validating anything I was saying, he told me that it was nonsense, that I was being too sensitive, that it was all in my head. Once, he shrugged and said, “Well, you don’t even look that Asian to me.”

My father didn’t have bad intentions and he wasn’t disrespectful of Asian people. He spent years of his life in Taiwan and China, learning the culture and language, making best friends with Asian men. He had connected with my mom at Ohio State University because they knew some of the same people in Taiwan.

But he was not my role model. In a place where Asian manhood had been obliterated, what I needed was someone to look up to. Someone who could understand my struggle and set an example. And my dad was not that person.

I realized then, at a young age, that I would have to be my own role model. A white man couldn’t teach an Asian man about masculinity. Nor could the media, with its tokens and stereotypes. I would have to plant my flag, rebuild my self-esteem, and figure out by myself what it meant to be an Asian man in this North American wilderness.

I knew I would have to be special.

There are three traits that the worst stereotypes take from Asian men in America: assertiveness, attractiveness, and creativity. On my quest, I would have to gain these three powers back. I couldn’t verbalize this back then—all I knew it as was, “I have to break out of my stereotype.”

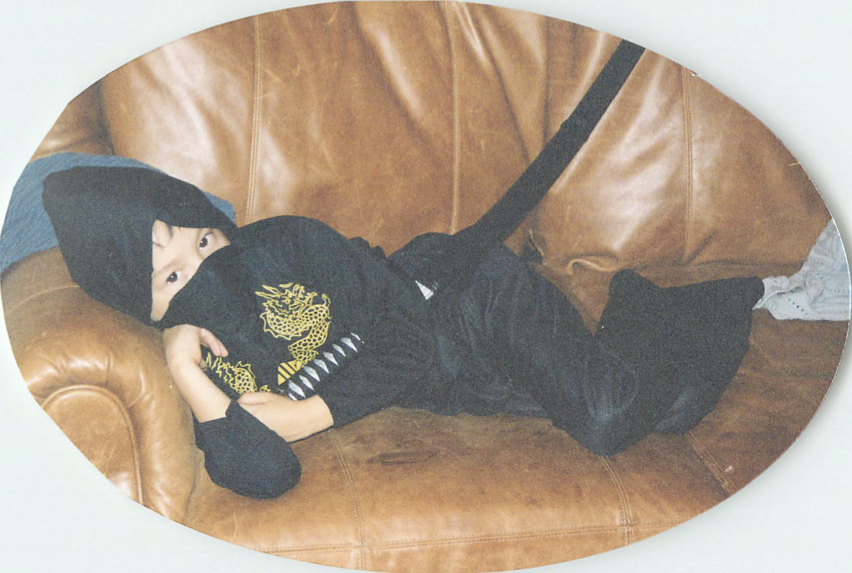

The first thing I did was pick up a skateboard. Fuck it. Skateboarding has always been a culture for outsiders. Unlike team sports, which were dominated by white and black kids; or academic teams, which were dominated by Asian kids; skateboarding took on everyone: poor, rich, black, white, Filipino, Indian. I applied my work ethic and got good within a summer. In this way, my first group of high school friends became skateboarders—a clan which I smoked, fought, and got arrested with.

Around this time, I discovered Jerry Hsu. He was a Taiwanese-American skateboarder who shared my mom’s surname. His video parts were art; he wore flannels and sunglasses. He was known as “a cool breeze.” Jerry was the kind of man I wanted to be. I remember buying his shoes and showing my friend the “Hsu” under the tongue and whispering, “That’s my name, too.” And he told me, “That’s so cool.” My friends also wanted to be Jerry Hsu. But they couldn’t. Only I could.

Finally I had something of my own.

I found other role models. Some Asian, some not. I remember watching a video of Gucci Mane smoking a blunt and freestyling in woods that looked similar to the ones behind my house. I thought, “I could do that.” Rappers said “Fuck white America” and became rich. I wasn’t black, but I wasn’t white, and if they succeeded, maybe I could, too. So I learned the language of hip-hop.

As I looked towards people of color as role models, my relationship with my dad disintegrated. My dad always had this rigid idea of who I should be: a Jewish youth group-going, baseball-playing, rock ‘n’ roll kid. And when I started to rebel against that, he became angry. He called me a disappointment. He called me an idiot. He called me a loser. And we stopped talking.

What my dad didn’t understand is that I was different from him—not just generationally, but racially. Of course I would gravitate to subcultures for outsiders. Truthfully, in another world, maybe I would have been that All-American, easygoing teenager. I could have joined team sports and Jewish youth groups and felt good among white people.

But I couldn’t. I saw the way Asian kids were treated in my high school’s locker rooms—the dick jokes, being picked last for teams. I saw the way Jews had treated me. My dad could go to a synagogue and be embraced. I went to synagogue and an older woman narrowed her eyes and asked me, “Are you visiting from China?”

So I continued on my own path. By the time I graduated high school I had published writing, I made a mixtape, I was a student leader. I took the girl who told me I was weird-looking to homecoming. I wasn’t quite there yet, but I was becoming my own man.

Of course, I’m still learning about who that is. Is a masculine man one who is happy and unbothered, calm in all situations? Or does he walk around with a scowl on his face, always ready for a fight? Does he weight-lift and drink protein shakes, or does he write poetry and drink soy milk? Does he romance one girl or does he sleep with as many as he can?

I don’t know. But I have an idea. My masculinity is inspired both by the East and West. Like the Western ideal, a man is independent and strong. Like the Eastern ideal, he is scholarly and adaptive. When I meet women, I am introducing them to a compelling world of the Taoist Bible “Chuang Tzu” and my family recipe of beef noodle soup—without being a cultural imposter.

After all these years, I have learned something about being an Asian man. I used to think it would be to renounce my Asian identity. Now I understand that it is to embrace it.

As much as we might complain about the Asian man’s representation in media and the dating world, other people aren’t going to magically change their perceptions out of sympathy for us. The only way to change the stereotype is for us Asian men to ultimately show that we are assertive, we are attractive, we are creative. And when we add in the qualities that make us Asian—our culture, diligence, knowledge—the knife of manhood becomes not only strong but exquisite.

I’m grateful for the challenge. It gives me a sense of duty in life—to set an example for the Asian and half-Asian kids who will come after. To be the role model that I never had.

It’s been years now, and my Dad and I have slowly repaired our relationship. The single biggest change is that he started listening. And he now understands his blind spots.

We went out to lunch the other day and he told me: “You know, this Jewish guy who goes to synagogue with us, he just got married to an Asian woman, and they’re having a son. I know you…” He trailed off, but got it out. “I know you had your hardships with that, and I wonder what advice I should give him.”

I thought for a long time. What advice would I give to a half-Asian boy entering the same world that I did? Who has a white dad and an Asian mom? Eventually, I told my Dad, “Make him proud of being Asian. Allow him to connect with his culture. Teach him to fight back when needed.”

“And when he comes of age,” I said, “tell him to come talk to me.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Zachary on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.