The First 35 Mins of ‘Wall-E’ Is Still the Best Thing Pixar Has Ever Done

A camera lowers at the start of Wall-E from high above space to a dystopian future you’ve seen before. The sun then fades through a Mad Max-ish hue, and some unpretty mountains of trash slide into view. During the stillness and silence, this metallic thing rolls by; a rusty, lipless, semi-literate thing blowing the tunes of “Hello, Dolly!”

Seeing Wall-E the robot for the first time back in 08 felt strange. He was bulky and square with Johnny 5 levels of bore—very different from the big eyed, anthropomorphic exaggerations of Pixar’s usual stock. He didn’t talk or come with subtitles, but minute by minute he’d let off these beeps and gestures that somehow defined a personality; organized, curious, inventive, and lonely. Pixar’s talent for expressing humanity through subtlety wasn’t a secret in 2008 (much of their history is from the silent short), but they hadn’t done it this well either. Ten years later, after a fresh watch, I strongly believe the first 35 minutes of Wall-E is still the most creative thing Pixar has ever done.

To “tell” you the synopsis of Wall-E with just words shows why Wall-E was so special to begin with: here’s a small robot dude who lives on Earth and never stops cleaning shit up for humans. Said robot encounters another robot named Eve, who leads him on a journey to outer space. There he encounters a happy but lazy space colony of humans in their cycles of consumption, blah blah, environmental message, blah blah blah.

A story told through this kind of summary can’t pop like Wall-E pops. You’d need the visual storytelling that separates it from any song or book. The most memorable sequence of all Pixar sequences aren’t special because of anything that was told through words, but by the little things you see.

Ever since my dropout days of film school, I was taught the same “show, don’t tell” psalm like it was a bible verse. When a scene was set, the wordless parts would stick out the most. In these visual moments, like any silent Charlie Chaplin film (The Kid, Modern Times), a lot had to be asked. As the audience, you had to give a shit for your own sake to fill in the details. This meant that creators needed to find alternative ways to express feeling.

Compared to standard lines of dialogue, the silent film has umph, because it trusts your understanding of the world. It believes in your ability to pick up on the subtleties of sadness, anger and hurt by drawing it from a real place. Pixar has mastered this, both before and after Wall-E like in the following examples.

The Incredibles (2004)

Take the first few minutes of The Incredibles. You got this oversized superhero Bob huddled in an undersized car during rush hour. I love how depressed my man Bob looks over here; he hates his routine, and needs a change desperately. Bob is relatable to the misery of being a job you hate because maybe you know you’re not doing what you are meant to do. The viewer then cares when he finally finds that calling.

UP (2009)

The first few (Pixar is evil) moments of UP gives us something similar to the above—a beautiful homage to a marriage that ended sadly (still evil) without a word. We understand exactly what we need to feel in this moment without the manufactured bullshit of “I love yous” or “I’m sad” to guide our way. It respects us for being human (hopefully) and in our abilities to recognize grief.

Now back to Wall-E: the best example to all that good “show” instead of “tell” shit. In 08, Pixar really gave itself no choice in the matter. Wall-E and Eve were were mouthless and tongueless designs that spoke very few words apart from names and “directive.” A regular moment of back and forth between two people had to replace gestures. And lengthy scroll sequences of exposition (descriptions and backstories) had to be replaced with silent scenes and interactions.

It was a hugely risky move for a film that featured characters without faces, but emotionally they somehow did it. Let’s take a look:

Scene breakdown:

At the two-minute mark, Wall-E is gathering obscure items and Pixar is giving a clever hint about how different Wall-E is from other robots; an AI with the needs of a human. Even I can identify with this lensy-eyed thing for what he exhibits; vulnerability.

It’s also hard not to notice the malfunctioned robots that look exactly like Wall-E, which gives a clue that our little guy is completely alone in this moment. All that guesswork about whether or not he had partners like him gets tossed out the window and it hits me like a gut check.

When the sun dies down, and he grabs a lunch pail on his way home. The routine itself looks a lot like human work and it’s what Wall-E sees as a routine.

And the collection of human oddities that he’s collected decorates his homebase showing a pride like our own, in the comfort of our homes.

Here, Wall-E watches Hello, Dolly!, a 1969 romantic comedy, presumably his favourite. As he reaches for a trash lid to craft a hat, it’s cute but it also shows how much he cares about what he’s seeing. This isn’t a film for Wall-E, he wants to be like those two dancing humans. He wants what they have, to be loved.

It shows in the money shot, where we see Wall-E’s opticals stare up into the night sky. Director Andrew Stanton—the same man that once said that loneliness was our biggest fear, whether we were conscious of it or not—tells us that Wall-E craves for something beyond his reach.

He’s been alone for far too long, and seeing him rock himself to sleep is great in the way that shows how much his daily routine isn’t cutting it.

This is just nine minutes in and we know so much. Other movies that try to build worlds as effectively usually go for number of lazy and boring methods. There’s the narrator approach like in the case of The Great Gatsby and the awful sounding Tobey MaGuire. Or the text method, involving some newspaper clippings like in The Hunger Games. The 35-minute sequence of Pixar’s Wall-E was instead an exploration around personal conclusions.

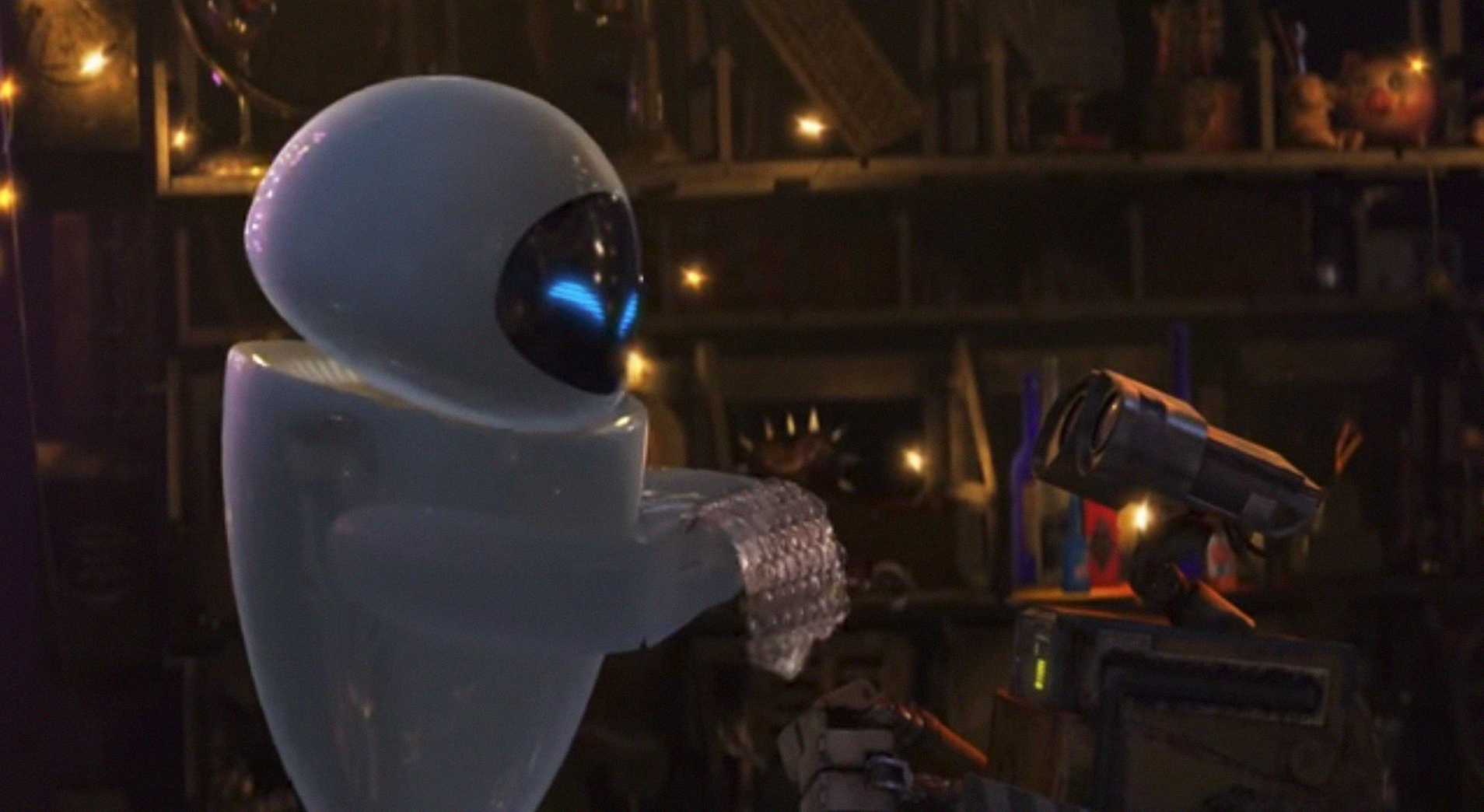

Skipping ahead, when Eve is first introduced, her elegance and shine gives her the air of the opposite sex (if robots cared for genders). She scans, does her robot shit and once alone, she goes for an an upward spiral of jet engined velocity.

She has a personality and a wild side. She also now has character beyond her robot purpose.

And clearly, Wall-E has a thing for her since she can probably be the answer to his loneliness.

Everything that happens next amounts to a montage of Eve doing her job and Wall-E following her around. I love that the tune of Louis Armstrong’s La Vie En Rose plays here, because he’s trying to get her attention and failing hard.

While she pushes him away at first, they finally begin to interact by seeing each other in a different light. He shows her his oddities he’s collected, and she finds pleasure in his kindness. At this point, the groundwork is laid and the film takes off in a more dialogue heavy direction that still stands strong from those first 35 minutes to the last.

The one thing that Wall-E understood above all Pixar animations to this day was the power in accessibility. A language can come with barriers. Text can be unreadable. A choice of dialect can feel alienating. But a head tilt, a gaze, or expression of love is universal. The stories we hold close aren’t wrapped best in how we “tell” them, it’s in the feelings and images that give them life.

In those first few minutes, Wall-E’s story about loneliness, friendship and hope still gives me life, and I prefer not to be told what that should feel like.

Follow Noel Ransome on Twitter.

Sign up for the VICE Canada Newsletter to get the best of VICE Canada delivered to your inbox.