The Companies Cleaning the Internet, and the Dark Secrets They Don’t Want You to Know

Every minute of every single day, 500 hours of video footage is uploaded to YouTube, 450,000 tweets are tweeted and a staggering 2.5 million posts are posted to Facebook. We are drowning in content, and within all of that content there’s undoubtedly going to be a chunk deemed as offensive – stuff that’s violent, racist, misogynistic and so on – which gets reported.

But what happens once you’ve reported that content? Who takes care of the next steps?

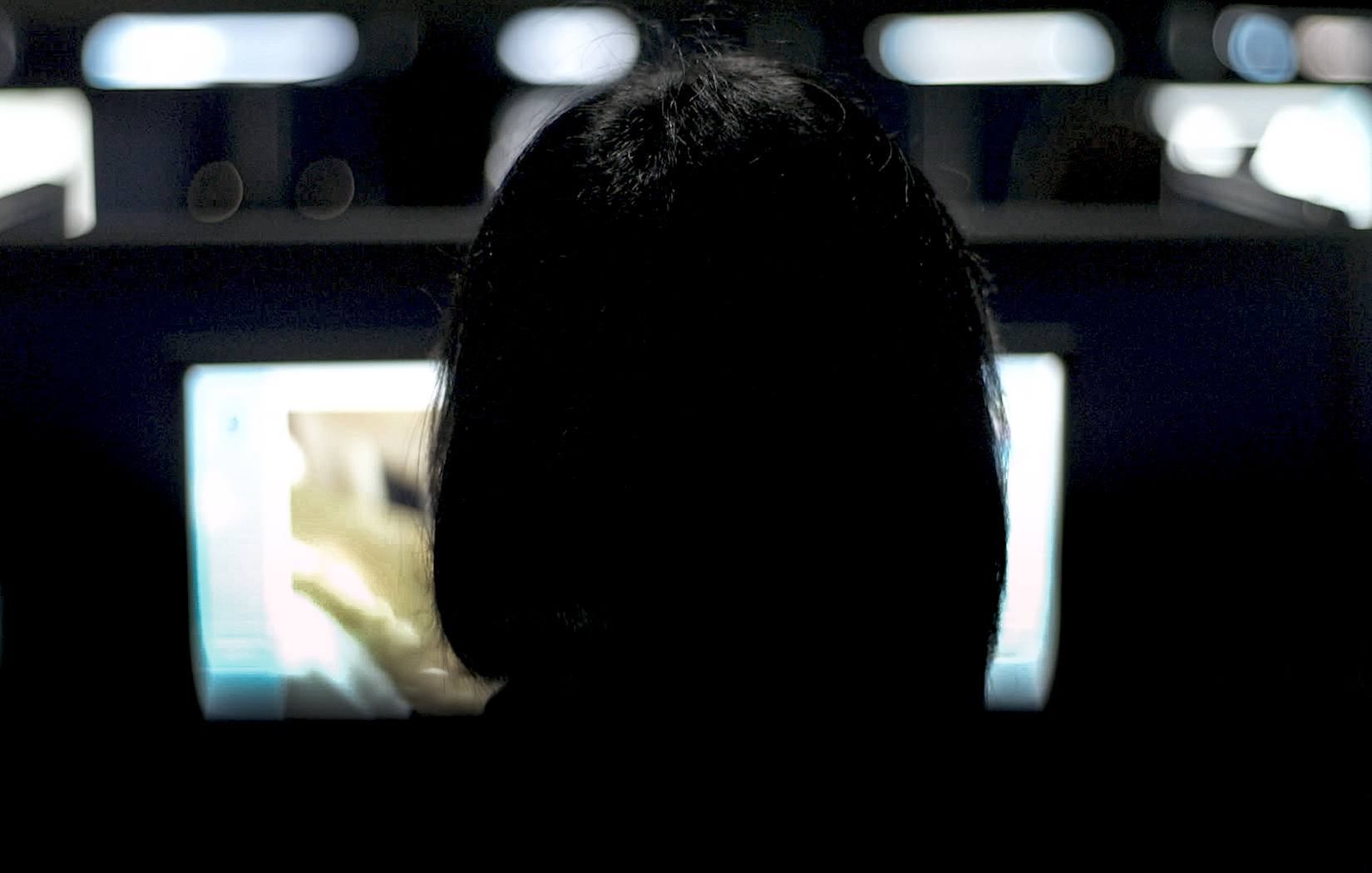

Directors Moritz Riesewieck and Hans Block have made a documentary exploring exactly that question, and the answer is much more depressing that you might have imagined. The Cleaners got its UK Premiere at Sheffield Doc/Fest in June, so I caught up with the pair shortly after to discuss how social media organisations are cleaning up the internet at the cost of others’ lives.

VICE: Tell me about what drew you to this subject and why you wanted to make a film on it.

Hans Block: In 2013, a child abuse video went on Facebook and we asked ourselves how this happened, because that material is obviously out there in the world but not usually on social media sites. So we began to ask if people were filtering the web or curating what we see. We found out that there were thousands of humans doing the job every day in front of a screen, reviewing what we’re supposed to see or not see. We learned that a lot of the work is outsourced to the developing world, and one of the main spots is Manila, and almost nobody knows about it.

We found out very quickly when trying to contact the workers that it’s a very secretive industry, and the company tried to stop the workers speaking out. The companies use a lot of private policies and screen the accounts of the workers to make sure that nobody is talking with outsiders. They even use code words. Whenever a worker is working for Facebook, they have to say they are working for the “honey badger project”. There’s a real atmosphere of fear and pressure, because there are reprisals for the workers; they have to pay a €10,000 (£8,800) fee if they talk about what they’re doing. It’s written into their non-disclosure agreements. They even fear they will be put in jail.

But you managed to track down some workers and ex-workers, and gained their trust for the film. Are these guys moderating all content or just stuff that gets reported?

Moritz Riesewieck: There are two ways the content is forwarded to the Philippines. The first is a pre-filter, an algorithm, a machine that can analyse the shape of, say, a sexual organ or the colour of blood or certain skin colour. So whenever the pre-filter is analysing and it picks up on something that is inappropriate, the machine will send that content to the Philippines and the content moderators will double check if the machine was right. The second route is when the user flags the content as being inappropriate.

So this pre-filter algorithm is effectively capable of racial profiling people under the justification of what? Trying to detect terrorists or gangs?

Hans: We’ve been trying to work out exactly how this machine is working, and this is one of the big secrets the companies have. We don’t know what the machine is trained for in terms of detecting content. There are obvious things like a gun or a naked sexual organ, but some of the moderators told us that skin colour is being detected to pick up on things like terrorism, yes.

What happens when something is deleted? Is it just removed from the user who uploaded it or is it removed universally?

Hans: It is taken down universally. Although, in one case, it’s different: child pornography. Whenever a content moderator is reviewing child pornography, they have to escalate this and then report the IP address, the location, name of user – all the info they have, basically. This gets sent to a private organisation in the States and they then analyse all the info and forward it onto the police.

Are the content moderators adequately trained? Both in understanding the context of what they are reviewing and also in terms of the significance that some of their decisions can have?

Moritz: I would say this is this biggest scandal about the topic, because the workers are very young; they are 18 or 19 and have just left school. [The companies] are recruiting people from the street for these roles; they only request a very low profile of skills, which is basically being able to operate a computer. They are then given three to five days training, and within that they have to learn all the guidelines coming from Facebook, Google, YouTube, etc. There are hundreds of examples they have to learn. For example, they have to memorise 37 terror organisations – all their flags, the uniform, the sayings – all in three to five days. They then have to give the guidelines back to the company because they are afraid someone will leak them.

Another horrible fact is that the workers only have a few seconds to decide. To fulfil the quota of 25,000 images a day, that means they have three to five seconds on each. You’re not able to analyse the text of an image or thoroughly make sure you’re making the right decision when you have to review so much content. When you click, you then have another ten options to click based on the reason for deletion – nudity, terrorism, self-harm, etc. They then use the labelling of the content moderators to train the algorithm. Facebook is working very hard to train AI to do the job in the future.

So the workers are providing the training to an algorithm that will eventually take their own job?

Hans: It won’t be possible for AI to do that kind of job, I don’t think, because they can analyse what is in the picture, but what is necessary is reading the context, to interpret what you are seeing. If you see someone fighting, it could be a scene from a theatre play or a film. This sort of thing is something a machine will never be capable of.

Are the workers trained for the severity and trauma of what they are going to see – death, abuse, child pornography etc?

Moritz: They are not trained for that. There is one moderator in the film who, only on her first day, after training and signing the contract, properly realised what she was doing there. She ended up reviewing child pornography on her first day and said to the team leader she was unable to do this, and the response was, “You’ve signed the contract. It’s your job to do that.” There’s no psychological preparation for them to do their work. They have a quarterly session where the whole team is brought into one room and a psychologist asks, “Does anyone have a problem?” Of course, everyone is looking at the ground and afraid to talk about their problems, because they are afraid to lose their job. It’s for a good reason that Facebook is outsourcing work to the Philippines, because there’s such a big social pressure attached: the salary is not just their own; it’s often for their whole family, of up to eight to ten people. It’s not easy to leave the job.

What’s the scale of the operation out there?

Moritz: We can’t know the exact amount, but we think that, for Facebook alone, it’s around 10,000 people. If you then add in all the other companies that are outsourcing this work to the Philippines, it’s around 100,000. It’s a big, big industry.

Bias is something that is explored interestingly in the film. You have a content moderator who describes herself as a “sin preventer” and is very religious, while another person is very pro-President Rodrigo Duterte and his violent anti-crime and drugs stance. Are they imparting their personal views, politics and ethics onto something that should be objective?

Hans: Whenever Facebook is asked a question about the guidelines they try to promote that the guidelines are objective and that they can be executed by everyone. That’s not true, and that’s what the film is about. It’s very important what kind of cultural background you have. There are so many areas in the guidelines that require you to interpret and use your gut feeling to decide about what you see.

Religion is a big part of the Philippines, Catholicism is very strong. The idea of sacrifice is crucial in their culture, the idea of sacrificing yourself to get rid of the sins of the world – to make it a better place. So, for a lot of the workers, it is viewed as a religious mission. They use religion to give the job meaning, and that helps them do it a bit longer, as when you’re traumatised through work you need to find meaning. On a political level, Duterte is very strong there and people believe in what he is doing. Almost all the content moderators we spoke to were really proud he won the election. Some of the people see this work as an extension of his work, so they will just delete what they don’t like in line with the country’s political views.

All eyes are on Facebook at the moment post-Cambridge Analytica. How do you think things are going to pan out in the area of content moderation?

Moritz: Zuckerberg, whenever he is asked in a testimony, says he will hire another 20,000 people across the network on content safety. But this is not the solution. It’s not about the number of workers – you can hire another 20,000 low-wage Filipino workers doing the job and it won’t fix any problem with online censorship. What he needs to do is to hire really well trained journalists. Facebook is not just a place to share holiday pictures or invite someone to your birthday anymore; it’s the most major communication infrastructure in the world. More and more people are using Facebook to inform themselves, so it’s very important who is deciding what is published. Think about if someone else decided what was published on the Guardian‘s front page tomorrow; that would be a disaster and it would be a scandal, but this is the status quo of the social media companies right now. This has to change, but this costs money, and the only goal of the companies is to gain more money… that’s why they hire low-wage workers in the Philippines.

Some of the moderation requests, such as terrorism, are even coming directly from the US government, right?

Moritz: Absolutely. The list of terrorist organisations that have to be banned on Facebook comes from Homeland Security, but obviously in different parts of the world we have very different ideas of who is a terrorist and who is a freedom fighter. This is a lie that Facebook has always stated; that they are a neutral platform, that they are just a technical tool for the user. It’s not true; they are taking editorial decisions every day.

How did you find the people who had left this job were getting on? Are they forced into a silence or tracked or anything?

Hans: When we were researching, there was one moment when the [content moderation] company was taking photos of us and they were then distributed to everyone in the company, even the former workers, with a warning that talking to us will lead to them being in trouble. There’s a really big atmosphere of fear that the company is spreading. One employee contacted us via Facebook, and he was really angry with us and telling us to leave the city, or something will happen to us. So even the former workers are still scared of speaking after leaving. We had lawyers on our team to protect them, however; we knew what was written into their contracts and what we can say in our film.

One of the greatest tragedies captured in the film is that it tells the story of a worker who died by suicide. As far as you’re aware was that an anomaly or is that happening on a larger scale and not being reported?

Moritz: It is a wider thing happening in the company. The suicide rate is very high. Whenever we spoke with content moderators, almost everyone knows about a case where someone committed suicide because of the work. It’s a problem in the industry. That’s why it was important to include that in our film. They need to hire proper psychologists to protect them. The man in question who took his own life worked in reviewing self-harm content and had asked to be removed from doing that several times.

Are these social media companies aware that people are killing themselves over this work, do you think?

Hans: Good question. I think yes. They do know, because we made the film, but this is also a problem with outsourcing; it’s so easy for Facebook to say, “We don’t know about that because it’s not our company and we are not responsible because we don’t hire them and we’re not responsible for the working conditions.” This is the price we, and Facebook, are paying for cleaning social media – people killing themselves. We have to pressure these companies as loudly as we can.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.