We Need to Talk About Our Generation’s Gambling Problem

“I was sat in, by myself, on New Year’s Eve, as a 20-year-old,” says David, now 21, from north-west England. “All my mates were out partying, but I sat in and slept all night, feeling like shit, because I’d just had my biggest loss to date: about £4,000 in one night.”

There are very few certainties in gambling, but one is: every generation has a problem. Go to a place where addicts typically gather – from betting windows to blackjack tables – and see adults of most ages broken down and grey. What’s different about the latest generation of gamblers, however, is that they’re becoming addicted earlier and more catastrophically, losing thousands before they’re even out of school, and tens of thousands in early adulthood.

Despite the numbers – about 156,000 addicts aged 16 to 24 in the UK, and 25,000 under 16 – their tale is rarely told. Instead, many young addicts feel like their addiction has been taken for granted, lumped alongside other less fashionable habits like alcoholism, while stories about new drugs, for instance, are written every day.

This disinterest is reflected in a chronic lack of services, with the NHS providing only one specialist clinic throughout the UK to treat gambling addiction, and many other services largely reliant on donations from the betting industry itself: a lousy £8 million a year from a revenue of £14 billion.

All this makes life as a young addict extremely isolating, forcing many into the darkest corners of the internet: message-boards where scared, sometimes suicidal 14 to 24-year-olds pour their hearts out to one another. “College Student who needs to stop gambling”, “21 Years old. £1k to my name. It’s time to stop” and “19 years old, stupid :(” read three representative posts on Reddit’s r/problemgambling forum.

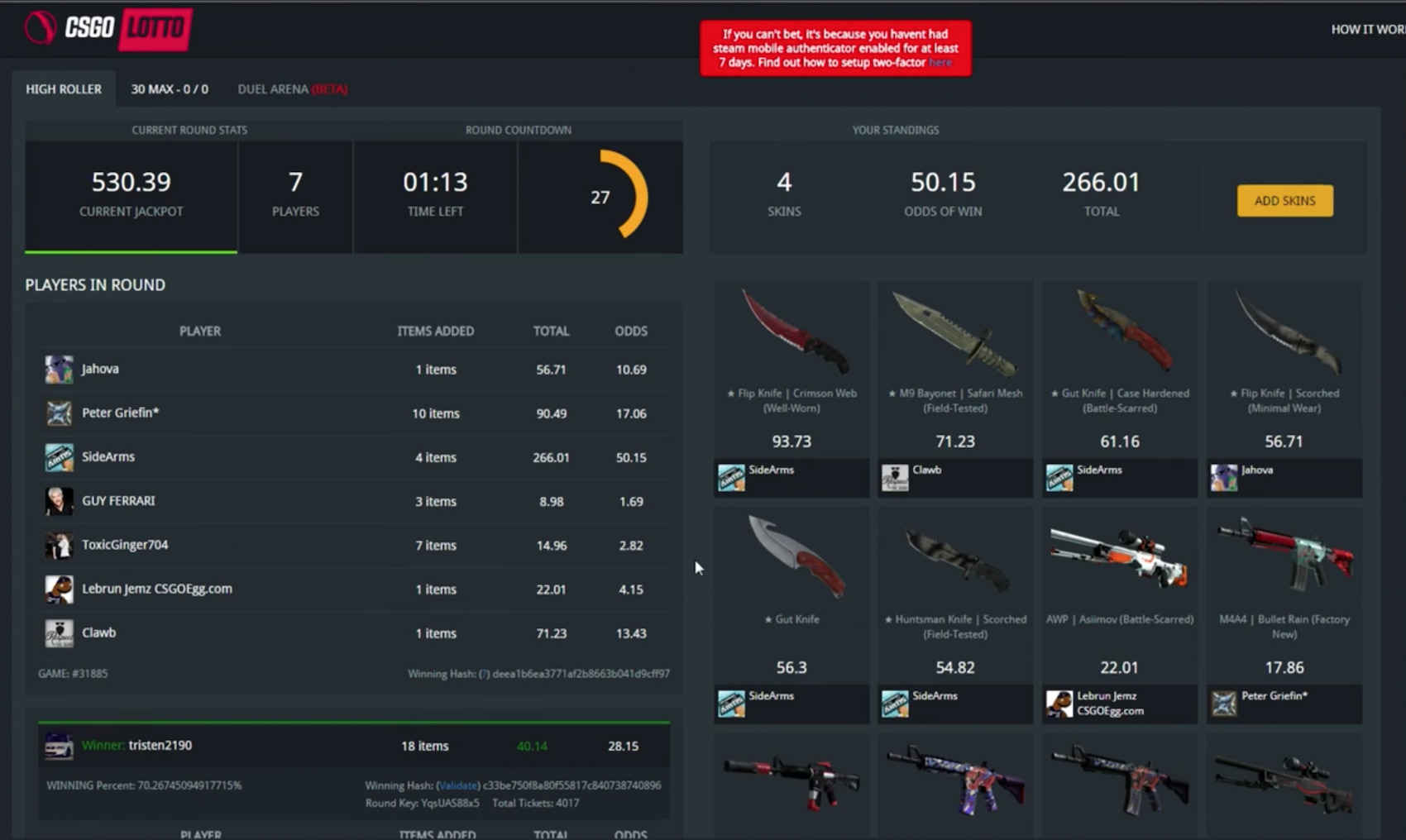

In 2018, the gambling-associated risks for young people appear down avenues old and new. For instance, far from the threadbare carpets of your local Ladbrokes, or the watered-down Malibu-and-Cokes of central London’s casinos, the same rough beast slouches toward teenagers in the shape of video game “skins” – digital decorative wraps for in-game weapons and other equipment. Some of these cost almost nothing, while the rarer ones can set you back hundreds of pounds and – in certain circles – have come to represent a level of status in the specific game’s community. It’s these skins which are put up as the prizes young gamers are gambling to win.

Lured by YouTubers offering free bets to millions of subscribers, teens are losing thousands gambling on these virtual guns, gloves and knives, on sites which frequently lack age verification, which are sometimes rigged, and which legally aren’t connected to the video games – like Counter-Strike and RuneScape – they’re spun off.

“My gambling started at around 15 through those games,” David tells me. Since New Year’s Eve, David has been in recovery, but is still paying about 80 percent of his wages towards a payday loan. “I think the appeal is the same as normal gambling: to win money and show off the amount of wealth to your friends. The scary thing is, it’s allowed for people under 18.”

This skin gambling industry is already worth $5 billion a year, but governments have only lately started to address the issue. In February, Denmark blocked access to some skin gambling sites, while in December the UK Gambling Commission said it’ll take criminal action where it can, but essentially can’t do anything without the help of parents and games companies. This follows Britain’s similarly laissez-faire approach to “loot boxes” – a slightly less exploitative way of betting around games like FIFA – which the Gambling Commission says isn’t actually gambling, despite Belgium and the Netherlands banning it on those grounds in April.

Gambling addiction – or problem gambling – is defined by the Royal College of Psychiatrists as betting that “disrupts or damages personal, family or recreational pursuits”. Of course, not everyone who bets on skins is a problem gambler, but teenagers – who these bets are aimed at – are extremely vulnerable, having low impulse control, low understanding of consequences and a lot of free time – all contributing factors to the addiction.

“Some of my main triggers were boredom and loneliness,” says David. “This feeling of emptiness and not feeling alive… gambling changes that through rushes of adrenaline, until the reality sinks in that you’ve just lost hundreds of pounds in the space of an hour or two. Consequences don’t come into your mind until you no longer have anything left to lose.”

The desire for wealth exists in all gambling addicts, regardless of age. With each big win comes the possibility of eradicating not just an unwanted life, but all the pain and losses that have mounted up over the previous weeks, months or years. As any recovering addict will tell you, though, every penny ultimately gets lost.

“I took out payday loans, store cards and overdrafts [to gamble with],” says Joe, 26, from the north-east of England. “Anything I could get, I did, and sadly the banks didn’t even question it. I was 19 or 20, spending thousands a month gambling, with £1,100 coming in from my job. It lasted for around six years, and even though I knew I should stop, by the end I was in so much debt that the only way out seemed to be to win it back.”

Like David, Joe is in recovery, but worries that his extensive losses will prevent him from ever getting a mortgage with his girlfriend: “I’m wanting to push on with my life, but that debt is always there, like a ball and chain attached to me.”

Initially, for most, it’s a big win that triggers the addiction, mixing with factors already mentioned, and others, like genetics. Then the process becomes everything: the emptying, obliterating void one enters into when on a streak (be it hot or cold) finally leads to losing becoming the goal, the only absolution left. As Jay Caspian Kang wrote in his 2010 essay on his poker addiction – one of the truest things written on the subject – “Only in losing could I find a story that made sense.” The bottom, however, is almost never The Bottom. The great lesson is almost never learned.

“I often tried to quit, but would inevitably end up in the same situation: a couple of days into the month with no money,” says Joe. “You feel like a massive failure, like once again you’ve let everyone down. I’d sit and think how I could survive the month, panic, cry, and then somehow reassure myself that things would be OK.”

If your awareness regarding the dangers of gambling is low when you’re underage, it’s unlikely to rapidly improve when you turn 18. The ways to ruin oneself, however, increase dramatically, from cards and craps to sports and slots.

If one characteristic unites this new generation of gamblers, though, it’s that – unlike their fathers and grandfathers – entering a betting shop is rare. Overwhelmingly, according to the forums and the people I’ve spoken to, they choose the digital shroud of apps, and also the faux glamour of casinos, where peer pressure, toxic masculinity and delusions of becoming the next Dan Bilzerian run free.

Britain’s gambling controversy du jour, then, about fixed odds betting terminals (FOBTs) and their maximum stake – recently lowered by the government from £100 to £2, taking effect in late 2019 – confuses many young addicts, who see them less as uniquely scandalous (though of course their damage is great) and more as high street versions of the same software that’s been draining them of will, money and life online and in casinos.

Of greater concern – at least to those trying to escape the darkness – is the acceptance of gambling in society, along with the lack of education around it. In Britain, betting companies promote themselves virtually unchecked, appearing in young people’s social media feeds; on podcasts they listen to, like James Richardson’s Totally Football Show; on YouTube channels they watch, like ArsenalFanTV and True Geordie; and during football games, in one in five ads.

Meanwhile, children are forever taught not to smoke, drink heavily or have unprotected sex, but rarely not to bet.

“Depression kicks in when I look at my bank balance and see it’s pretty much empty. When I do win, I tend to keep gambling the next day and the day after, until I’ve completely run out of money. At my worst I’ve lost over £13,000 in one day.” – James, 23, Newcastle upon Tyne.

The struggle of young addicts on boards like Reddit’s r/problemgambling is of course shocking, but they at least know they have a problem. Thousands of others convince themselves that their loved ones are overreacting and that the devastation they cause – like the stealing and substance abuse addicts sometimes succumb to – is nothing compared to their inevitable success.

James from Newcastle upon Tyne knows all about the drinking that gambling can lead to. A month since he last relapsed, he remains about £10,000 in debt. “When I gamble, I tend to lose all inhibitions,” he tells me. “For me, drinking seems to come naturally with it – however, I feel so euphoric from gambling that I don’t feel the alcohol take effect, which means I drink myself into blackout. Sometimes I start gambling straight after work, at 5:30PM – drinking two to three pints an hour – until 8:00AM the next morning.”

Gambling’s effect on British university students is similarly stark, with many betting to cover living costs, resulting in lost loans, one in eight missing classes and around 100,000 having some form of gambling debt. Reasons for this may also include the tactics casinos and bingo companies employ, such as discounted drinks, poker leagues, flyers sent to accommodation and stalls at freshers’ fairs.

The industry’s grip on millennials can partly be traced back to Labour’s 2005 decision to deregulate gambling, allowing profits to roughly double since that time, along with the amount of tax paid: now £2.7 billion a year. The agreement back then stipulated that the industry would donate 0.1 percent of its revenue towards recovery, but it has consistently fallen short, paying just £8 million in 2016 when it should have paid £13.8 million. Also notable is that, between January of 2016 and September of 2017, out of the 187 gifts received by MPs, almost a third came from betting companies.

Despite the lack of resources at an institutional level, several services are still available to help young addicts, like the GamCare helpline; Gamblers Anonymous; private rehabs; charities like Aquarius and StepChange, which manage debt that’s gotten out of control; podcasts like Gambling Still Sucks; and of course boards like r/problemgambling, where the sense of community is strong, and where someone who’s always lost more than you is there to tell you that recovery, happiness and a long life remain possible.

Tactics many find useful also include: handing over control of your money to a loved one, installing anti-gambling software on your phone and computer, and – if you’re over 18 – putting yourself on “Self-Exclusion” lists, databases casinos and bookmakers have access to, which effectively ban you from going inside.

Ultimately, though, proof that more needs to be done lies in the worrying number of suicides happening in Britain among young gamblers. The National Council on Problem Gambling (NCPG) has estimated that one in five problem gamblers attempt suicide – about twice the rate of other addictions – while a study of Australian hospitals found that 17 percent of all emergency room admissions for suicide are gambling-related.

Take Joshua Jones: a 23-year-old accountant who leaped from a London skyscraper in 2015 because of, his father says, “shame” over gambling. Joshua had blown his student loan in university, but then began taking out payday loans at stratospheric interest rates. There was also Jack Ritchie, a 24-year-old who took his own life in Sheffield last November, whose parents have now set up a charity called You Don’t Know Jack to raise awareness of gambling’s destructiveness.

The life of a young addict is undoubtedly stressful, and seeing how a severe mental health episode could develop while trying to maintain that lifestyle isn’t hard. Jake, 23, from Birmingham – who last relapsed a month ago and has lost over £50,000 in his young life – describes a typical day: “I wake up in the morning and worry about money straight away. The whole way to work, I’m checking bank balances and managing credit cards and loans, then in work I do nothing but think about how I could get a better job if I didn’t have all this debt hanging over me. When I go home I don’t sleep because I’m too worried; I’d say I get about three hours a night.”

Joe from the north-east tells a similar story: “I’d lay in bed at night panicking, crying myself to sleep because I was terrified of what might happen. There seemed no way out, and gambling has a huge stigma attached to it, so you feel you’ll be judged for it more than many other addictions.” He then tells me he considered suicide, before deciding, instead of his life, it was the addiction he wanted to end.

Decreasing FOBTs’ maximum stake has shown that the government isn’t completely tone-deaf on problem gambling. However, politicians’ overall favouritism towards the industry, along with their lack of funding for recovery, is clearly not only making this generation’s plight worse, but enslaving future ones to the grimmest of fates.

The house might always win, but must the most vulnerable in society lose their money, prospects and sometimes their lives in the process?

If you think you have a gambling problem, please contact the GamCare helpline on 0808 8020 133. If you’re having suicidal thoughts, please call the Samaritans on 116 123.

This article originally appeared on VICE UK.