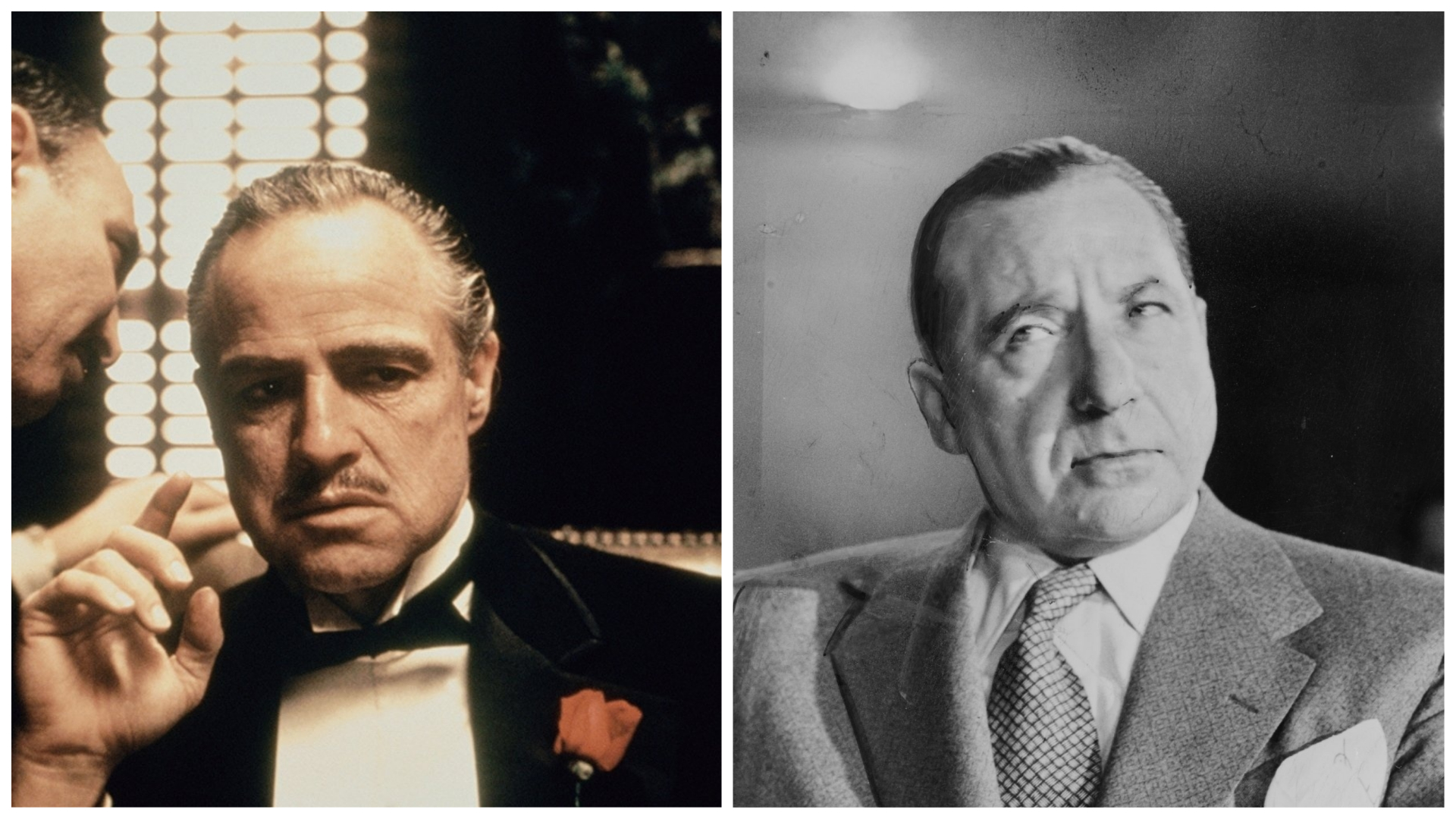

Meet the Unconventional Mafia Boss Who Inspired ‘Godfather’ Don Corleone

In May 1957, New York gangster Frank Costello was the victim of an assassination attempt orchestrated by Vito Genovese, his rival for control of what had once been Lucky Luciano’s very own crime family. Luciano was in exile in Italy at this point, and Costello and Genovese had long been on a collision course as they ascended the ranks of a surging criminal underworld. Genovese was a bit more rash—a bit more hungry, maybe—and convinced Vincent “The Chin” Gigante to whack Costello. Somehow (the bullet grazed his head but did not puncture his skull) the Mafia Don survived. He saw the writing on the wall, however, and began bowing out of the life, retiring to his home in Sands Point on Long Island. Costello wanted to do what he could to live out his life in a normal way, die in his own bed, and not at the hand of an assassin, despite his Cosa Nostra roots.

In his forthcoming book, Top Hoodlum: Frank Costello, Prime Minister of the Mafia, Pulitzer Prize–winning scribe and noted Mafia historian Anthony M. DeStefano recounts the life and times of Costello, a man whose political connections enabled the Mafia to basically do whatever it wanted. VICE talked to DeStefano to find out just how much Costello served as the model for Mario Puzo’s Don Corleone in The Godfather, the various powerful politicians (including a future president) he crossed paths with, and how close Costello got to achieving the legitimacy he craved.

VICE: It’s often said in mafia obsessive circles that Frank Costello was the model for Mario Puzo’s Don Corleone. Did Puzo ever confirm that?

Anthony M. DeStefano: I don’t know if Puzo ever said it, but Costello’s image was part of the inspiration. I think there are possibly two others in the mix. Don Joe Profaci, who was the olive oil king—there was an olive oil connection to Don Corleone and his business life. Also: Carlo Gambino. Costello didn’t have any family, but Gambino and Profaci did. I think that those are the three mafia leaders who inspired and contributed to the characterization of Don Corleone. It’s a blend of all three.

Why do you think real-life mobsters like John Gotti and Al Capone get a lot more play and notoriety in pop culture than someone like Frank Costello, even though Costello arguably had more power and reach at his peak?

Costello was not a killer. He was not a tough guy. He was more of a politician, a facilitat, a diplomat of sorts. Gotti and Capone got more publicity because Capone was [portrayed] in The Untouchables. He was a really major gangster in the mid part of the 20th century. Gotti wanted to be a gangster and he sort of filled a need in the 1980s and early 90s to have some sort of mob [figure] like they had in the old days for the press and public.

What’s your sense of where Costello’s craving for the respectability of high society came from—his desire to elevate himself above the mob?

It began with some him coming from a poor immigrant background and family. Seeing how the rest of the upper crust society lived, he aspired to that respectability because he didn’t have it. He wanted to be remembered as somebody who was legitimate because he wanted to shake the poor, sort of immigrant, gangster image. But in the end he really couldn’t shake that. He cursed the gangster life that he’d grown up in. He was a product of the times, because a lot of these guys didn’t really have much in terms of family resources or mainstream connections. They had to make it on their own, doing things that were illegal, but which the public craved, like booze and gambling.

How mobbed up were New York politicians and cops in Costello’s time compared to the rest of the country?

The police were involved in Prohibition in the sense that they were moving liquor and smuggled booze for the gangsters, off-loading shipments. The politicians saw the mob as a source of cash, which politicians needed. But if you look around the country, in places like Kansas City, the mob also had influence there. Down south too, in the Arkansas area. The mob, such as it was in those other cities, had similar clout, but in New York it was more magnified—for the obvious reason that New York was the media capital.

Everyone has heard about Tammany Hall in its heyday, but I think readers will be surprised to learn just how involved people like Costello were in mainstream political events.

In 1932, Costello was with delegates at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and worked to secure Franklin D.Roosevelt the presidential nomination. He was at the convention with Tammany leader Jimmy Hines, who years later would be convicted of corruption. Hines took regular cash payments from gamblers, controlled a city magistrate who dismissed criminal cases on Hines request, had sway over the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, and protected Dutch Schultz’s gambling operation.

You mentioned the media megaphone, which seems obvious, and it was always a big trade center. But why else was New York such a perfect breeding ground for bootleggers, mafiasos, and the dirty politicians they work with, even compared to other major cities?

New York had the five families—that structure was put in place by Luciano. The democratic machine, back in the day of Tammany, was getting poorer as time went on—we’re talking in the 20th century—and they needed a good source of cash. The gangsters were that source of cash because they had a big stockpile of money from Prohibition. They were able to entice the politicians, who the mobsters needed to run favours. To get police on their side. To get government on their side. To sort of create a structure, in a political sense, that was favourable to organized crime.

New York has been pretty dirty politically in recent years, with several once-untouchable political leaders in Albany going down. Is the corruption now comparable to that era?

I don’t think the mob has factored in New York City corruption for decades, since the 60s or 70s. But you still have, essentially, the basic motives for corruption: money and power. The way the political system is here, reliant on political donations and money, it’s [ripe] for corruption.

How much of Costello avoiding major prosecution and serious prison tiume—despite his prominence—was luck as opposed to being crafty or careful?

Luck played a part of it. He was coming up in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, when the laws weren’t as sharply focused and tuned as they are today with racketeering statutes. When they did go after him for Prohibition, and for income tax, they just didn’t have the goods on him. In some ways, he was the Teflon Don of the time because he avoided the [cases that tripped up his contemporaries]. He was investigated for a number of things, but they didn’t go after him until really later on, when they did finally get a federal contempt citation on him because he didn’t want to testify before Congress.

How close to legitimacy do you think Costello actually got in his lifetime? Did he achieve what he wanted, or was he still fighting for more?

In his mind he came close, but in society’s mind, he had some distance to go. Fiorello LaGuardia [the New York City mayor] went after him with hammer and tongs, going after his gambling operations in the city, calling him one of the chiselers and punks with the racketeers. He went after him with gusto and caused a problem because that forced Costello to shift his gambling operations down south to Louisiana. The attention that Costello got from law enforcement prevented him from shedding that image of a racketeer, of a mob boss. You saw this in the Kefauver hearings.

Costello thought he could acquit himself well in his testimony, but it came out very poorly. People came away shaking their heads and figuring, “Well this guy is doing something wrong or has done something wrong in life.” He was never really allowed to shake the image. Even though you’re making your money legitimately, if you have that bad image, that reputation, it’s gonna prevent you from being so-called legitimate. I think the impression was that he wasn’t legit. No matter what he thought. No matter what he was doing.

Learn more about DeStefano’s book, out June 26, here.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.