We Visited Sheela from ‘Wild Wild Country’ at the Care Home She Runs in Switzerland

This article originally appeared on VICE Switzerland

It was a cool July day in 1986 when Ma Anand Sheela strolled into a courthouse in Oregon to plead guilty to attempted murder, grievous bodily harm, wiretapping and immigration fraud. Sheela was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and fined $470,000.

“My main aim was always to protect Bhagwan,” she said then, of her spiritual leader Osho Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, still grinning as she was led away in handcuffs.

Today, Sheela runs two residential homes for disabled people, near Basel in northwest Switzerland. One of the homes is Wohnheim Matrusaden, perched on a hill that’s surrounded by a forest, looking over the small, 900-strong village of Maisprach. Sheela has lived and worked here for more than 20 years.

When I arrive, Sheela is sitting at a table at the front of the house, chatting and drinking coffee with a small group of people. Though she’s welcoming, there’s something distant about her. As we head upstairs to her room to chat, she leads me past patients’ rooms and down corridors that smell of disinfectant. At 70 years old, she moves fast and purposefully, as if she’s late to an important appointment.

Back in the 1980s, Sheela led a group of people who found spiritual comfort and fulfilment in the Rajneesh movement – a collective of followers of the Indian religious leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. (Bhagwan translates as something between “god” and “guru”). For four years, Sheela was the group’s spokesperson and head of the movement’s commune in Wasco County, Oregon, known as Rajneeshpuram. She was also Bhagwan’s personal secretary and confidant.

The Rajneesh movement – which some in Oregon called a sex cult at the time – caused plenty of controversy in the 1980s; the battle between the group and Wasco County locals is the main focus of the recent Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country.

If you’ve seen the series, you’ll know this battle escalated to an alarming level.

In 1986, members of the commune, including Sheela, pleaded guilty to a number of crimes committed against both local officials and ordinary residents. Under a plea bargain arrangement, Sheela and Ma Anand Puja – another senior figure in the group – admitted their roles in a 1984 food poisoning attack that affected more than 750 people, which was intended to influence a local election and remains the largest biological terror attack in US history. The group also attempted to assassinate US State Attorney Charles Turner, who had his sights set on Rajneeshpuram.

The documentary series mostly paints Sheela as the instigator of these plots. However, she has said she was merely following the wishes of her “boss”, Bhagwan.

“I’ve never been interested in meditating,” Sheela tells me, sitting cross-legged on a rug in her room, shifting quickly from one thought to the next without any warning. “With mentally ill people, you always know what you’re going to get. But the psychologically healthy think that they’re going to achieve enlightenment or be led to enlightenment…” She breaks off and smiles. “Bhagwan always got so angry when I told him that members thought they were now enlightened. He’d then say, ‘These stupid people and their enlightenment!’ Bhagwan knew exactly what he was selling. It’s surprising how dumb people could be – some of them had doctorates.”

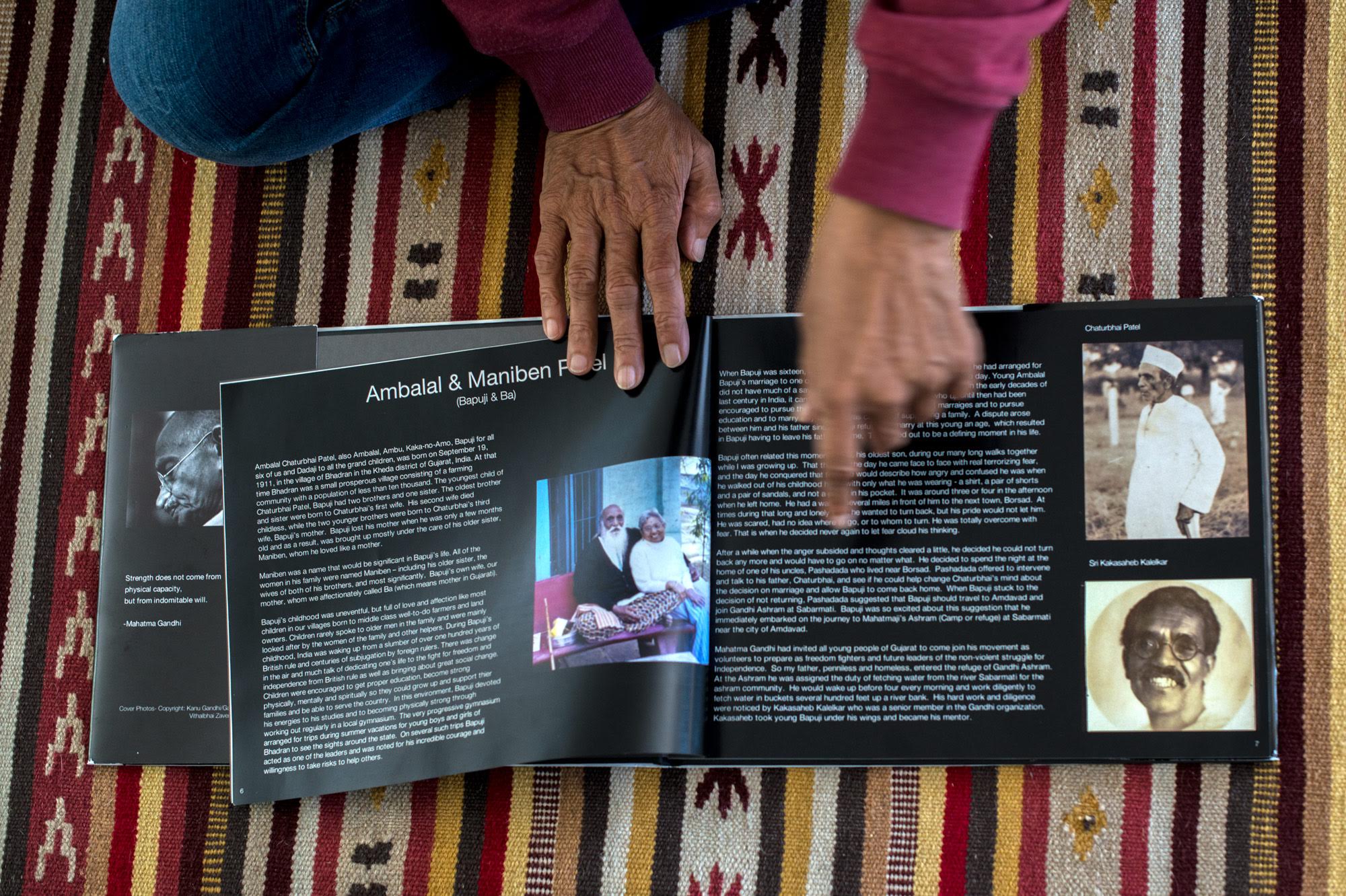

Sheela’s father introduced her to Bhagwan when she was still a teenager. Just like her, her father was close to another powerful religious leader. “He was a student of Gandhi and was trained in his ashram,” she says proudly, before grabbing a black book from her bookcase. She opens it gently and flicks through until she finds a letter. “Gandhi sent my father this letter,” she tells me. “Gandhi only trusted a few people, and my father was one of them. He knew that when he gave my dad a task, it would be done properly.”

There are obvious parallels here: as documented in Wild Wild Country, Sheela was more than happy to do whatever it took to keep Bhagwan happy.

Before Sheela’s trial, Knapp told the FBI, “Whenever Sheela said something, everyone accepted that she was speaking on behalf of Bhagwan.” Knapp also believed that Bhagwan knew everything that was going in Rajneeshpuram, including the deliberate poisoning of 751 people in Oregon. In an interview with German magazine Der Spiegel in 1985, the guru himself explained, “When others use violence, we will meet that with violence. That means an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

In the Netflix documentary, Rajneeshpuram’s neighbours constantly refer to the Oregon commune as a sex cult. At the time, Bhagwan would speak often of the virtues of free love and maintaining multiple lovers. “I don’t have a sex life anymore,” Sheela smiles today. “I don’t miss it, though. My life here is quiet and relaxed.”

In Rajneeshpuram, however, her sex life was very different. “One of my lovers was South African. He was so good in bed. I called him my caveman, because if he saw me he would grab me, throw me over his shoulder and run away with me,” she says, leaning back and shaking with laughter. “Of course we kissed and cuddled in public. But walking around, you never saw people openly having sex.”

If sex was encouraged, having children was not. When I ask Sheela about Bhagwan’s then-partner, Vivek, and her terminated pregnancy, her mood suddenly changes. “I’m sure she got pregnant on purpose,” she answers, her voice raised. “He warned her that if she didn’t get an abortion, she would have to leave the commune with the child. Bhagwan had always made it clear that children were a distraction from his spiritual path. To him, children were a burden. I don’t think his views were harsh or unfair.”

Everything was going fine in Rajneeshpuram, Sheela says, until Bhagwan started hanging out with the wrong people. “Rich and famous people wanted to be seen with Bhagwan, to feel special, to sit in the front row, so to speak,” Sheela scorns. “They took drugs with Bhagwan, which he eventually became addicted to. I couldn’t convince him to give it up, and because it was my job to protect him and I couldn’t, I decided to leave the movement.”

On the 16th of September, 1985, after Sheela left the group, Bhagwan gave an interview to an Australian TV channel attacking her. “Sheela has proven that she is not a real woman, but a real bitch,” he said, accusing her and other members of the Oregon commune of being behind the salmonella poisoning and other crimes. “Either she’ll eventually kill herself because of her guilt, or she’ll spend the rest of her life in prison.”

“Everything I did was based on Bhagwan’s teachings,” Sheela explains. “But there came a point when I wasn’t willing to compromise my integrity. I knew that Bhagwan was a vengeful man, so I decided to go along with everything I was accused of.”

Sheela was released for good behaviour after serving just under three years of her 20-year sentence. In the late 1990s, she moved – “penniless” – to Switzerland, where she married Swiss citizen, and fellow Rajneesh follower, Urs Birnsteil, and got a job as a carer for an elderly married couple. That experience, combined with her time in Rajneeshpuram, convinced her that her true calling was looking after others.

At the end of our day together, I feel like I’ve gotten to see a compassionate side to Sheela. Nevertheless, as she’s shown in the past, she can be manipulative when it comes to her interactions with others.

Just before I leave, Sheela suddenly tries to convince me that she never did anything wrong, offering to send me an email she received from Bhagwan just before he died as proof.

What Sheela eventually forwards me is a letter from a former member of Rajneeshpuram, who details a conversation that he apparently had with Bhagwan in August of 1986. In it, Bhagwan said that Sheela “was not the perpetrator, but a victim”. Furthermore, it reads: “Sheela is not a criminal, and anything that she did, she did to protect the commune.”

All these years later, Sheela is still trying to convince the world that she’s somehow innocent. It reminds me of what she said about her past actions when we were sat together on the floor of her room: “I don’t think that any of us acted criminally,” adding with a smile: “If I really had criminal instincts, I would still be committing crimes now.”

This article originally appeared on VICE CH.