This Black Woman Preacher Wants to Dismantle Religious Patriarchy

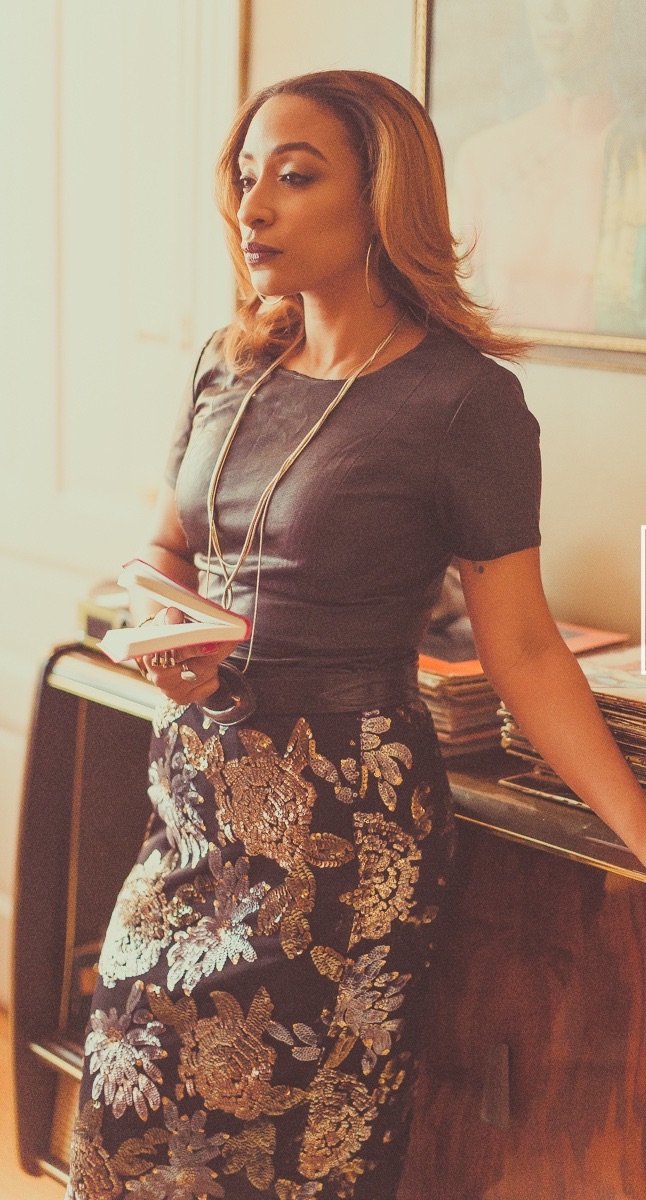

A Google image result for Reverend Neichelle Guidry brings up an image of a young black woman in a magenta dress standing in a pulpit, with a microphone placed in front of a statement necklace. Another shows a cold shoulder cutout top paired with clerical stole.

This image isn’t what our cultural imagination usually conjures up when they hear the word “pastor.” A Google image result for “pastor” shows pages of white men with collars and black men in robes. There’s a few pairs of khaki pants and skinny jeans scattered about, but it’s mostly pages and pages of men in suits. In our cultural imagination a preacher is male and his wife is in the front row.

Guidry is working to change this picture.

“It’s not just men who perpetuate patriarchy,” said Guidry, a 33-year-old single black female pastor who currently serves as the Dean of the Chapel at Spelman College. “You have women who don’t believe women should be ordained. Don’t believe women should preach. Don’t believe women should wear that dress in the pulpit.”

“This has been my fight—to really shine a light on those systems,” she added.

“I felt the weight of my womanhood in the black church,” said Guidry, who has been involved in religion her entire life, and has a Ph.D. in liturgy and homiletics, the art of preaching and writing sermons.

Guidry recently moved to Atlanta to become the Dean of the Chapel at Spelman, a Historic Black College. Previously, for six years, Guidry served as the Associate Pastor at Trinity United Church of Christ on the South Side of Chicago. Guidry said that, through her pastoral roles and scholarship, she felt called to raise awareness and help overthrow the systems she operated within.

Guidry, 33, believes that being a black millennial woman in the church is a “perfect storm of marginalization.”

Work didn’t always look like “the mecca of Black women’s education and liberation, where the stories and struggles of women are given adequate space” as Guidry has described life at Spelman. In previous pastoral roles, she longed for peers of her own as the youngest on staff and the only black woman. She wanted to talk shop, mentor, and be mentored, and have people to lean on. “There’s no lack of millennial clergy,” she said. “What there is a lack of is adequate spaces for millennial clergy to be authentic.”

Guidry considered the possibility that other black women in her situation—deeply called to ministry but in a less than ideal environment—were out there. To find them, she created a space for connection. In 2012, Guidry launched ShePreaches.com a virtual community for black women in ministry. On launch day, ShePreaches.com received over 3,000 visits, according to a New York Times profile of the community.

The site is intended to be a sounding board and a fellowship, but it’s also an online magazine where black women in ministry write articles about sexuality, relationships, family, and spirituality. “People still want fellowship and togetherness and unity,” Guidry said. “They still want to feel like something spiritual is happening in them and around them but they’re not going to these big ecclesiastical buildings to get that.”

One blog post on ShePreaches is titled “Furious Dancing” a nod to an Alice Walker quote: “Hard times require furious dancing.” An excerpt of the post reads: “YOU, young, Black woman, deserve to be nurtured, not used nor abused. If your church won’t ordain women, but you can pay all the tithes, fry all the chicken, clean all the toilets, design all the programs, print all the bulletins, usher all the people, but you’re still being called ‘sister’ instead of ‘minister,’ or ‘evangelist’ instead of ‘pastor,’ you might have to march your stiletto-clad feet right out of those church doors.”

ShePreaches isn’t about leaving church so much as reimagining it. “At our worship services, you only hear black women under 40 preaching on subjects having to do with the particularities of black women’s lives [like] racism, domestic violence, menstruation, divorce and mental health,” said Guidry. “This came to be an entrepreneurial kind of grind for people who were called to ministry but were scarcely given space and opportunity to do the work that our soul must have.”

Guidry is not alone in leveraging the internet for a new kind of ministry. There are other sites, like Black Millennial Cafe, aimed at black Millennials; The Black Theology Project, which positions itself as a theological resource for the black community; and Red Lip Theology, which caters to black women. “We are utilizing this moment of content creation to do ministry in non-traditional ways and spaces,” Guidry said. “It’s not that millennials don’t go to churches. It’s that churches can’t hold us.”

Being held, according to Guidry is ultimately about acceptance and love within a spiritual setting. She said, “Being accepted just for who you are and for everything that you bring and for the things you don’t bring and still being good enough to just be loved without judgment, without pretense, without ‘We’re going to try to make you this and into that.’ ”

ShePreaches is where Guidry found other young black women in ministry and with them, she intends to win. Winning, for her, looks like generativity—creating more black women in ministry through mentoring, encouraging a culture of support between women, and making a culture devoid of competition.

Guidry receives support in her personal and professional life through an independent social group called The Hedge of Protection (The Hedge for short), a nod to Psalm 91. The group consists of other prominent women in ministry with significant sized online platforms who met one another when they were fellow speakers at WhyChristian, a popular conference series created by author Rachel Held Evans and pastor Nadia Bolz-Weber.

“We have vowed to never compete with each other,” Guidry said of The Hedge. “We’re on a group text 24/7 with texts that say, ‘Hey, I’m going through this today,’ ‘Hey, I have this today can you pray for me,’ ‘Hey, I just need some guidance.’ It’s collegiately, it’s love. I feel like we’re winning; we have each other.”

Guidry practices womanist theology, a religious framework seen through the lens of a black woman. It was established through Sisters in the Wilderness, a seminal 1993 text by Delores Williams, professor emerita at Union Theological Seminary.

Womanist Theology validates the role of women in religious texts through revising and reconsidering traditional Biblical interpretation and religious practice. Nyasha Junior, assistant professor in the department of religion at Temple University and author of the forthcoming book, Reimagining Hagar: Blackness and Bible, wrote in an email that, “Williams uses African-American women’s experiences as a source for theological reflection. She draws parallels between the events within biblical Hagar’s narrative and historical experiences of African-American women, including enslavement, surrogacy, and encounters with God.”

In the Bible, Hagar was sold as a maid and given to Abraham by his childless wife Sarah in order to bear his child. Guidry told me that “Hagar has been pinned as a typical ‘welfare queen,’ when really, she was a slave who, without agency or power over her own body, was raped and impregnated by her owner at the order of her mistress. Reducing women, in the Bible or elsewhere, to a particular stereotype (often sexualized, ie temptress, prostitute, etc.), or to an event that happened to them (victim, widow, barren, etc.) flattens her humanity and her narrative. Redemption happens when we read about her context and try to understand her within it. It means telling a fuller story that entertains the possibility that perhaps there is more to her than what is readily presented in text and in theory.”

Not long before Guidry left Chicago, she preached a sermon called “Trick the System” inspired by the book of Exodus, a biblical account often associated with Moses, who led the Israelites out of Egypt by crossing the Red Sea. In her sermon, Guidry didn’t mention Moses but she did draw upon two heroines from Exodus named Shiphrah and Puah, midwives who helped Hebrew women give birth. Pharoah ordered the midwives to kill all the male babies and let the females live. Shiphrah and Puah defied those orders, permitting baby boys to live.

Guidry’s sermon elevated Shiphrah and Puah’s work as inspiration for listeners to work to save the children in their communities from systems of oppression, an imploration given in reaction to police violence against black boys.

“God has given us tools and words to redeem the gospel in the way that redeems people’s lives,” said Guidry. “When I think about Jesus, there were distinct moments in the gospels where he was very adamant about getting alone and going to solitary places but when it was time to do ministry, not only was he with the twelve disciples; he was with the needy masses, doing things for them that the system couldn’t do.”

Religion has served as both a language of oppression and a language of liberation. With a black woman preaching, there is an opportunity for liberation to come through those who have been oppressed. What is preached makes a huge difference but so does who is preaching. “Any time a black woman occupies the space of a pulpit her very body is an indictment on the systems that try to keep her out of that space,” said Guidry. “Our bodies prophesize and preach before we even say a word.”

This story is a part of VICE’s ongoing effort to highlight the contributions of black women around the globe who are making a difference. To read more stories about strong black women making history today, go here.

Follow Gina Ryder on Twitter.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.