‘Beauty and the Beast’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’ Were Actually Queer as Hell

You may never have thought “The Mob Song” from 1991’s Beauty and the Beast was lyricist and playwright Howard Ashman’s way of fighting bigotry. The crowd shouts, “He’ll come stalking us at night / Set to sacrifice our children to his monstrous appetite,” referring to the Beast. But the lyrics were also meant to reference the slanderous stereotypes against gay and queer men. Howard, the recent biographical documentary from Don Hahn, the original producer of Beauty and the Beast, drives this point home by juxtaposing the song against images of religious protestors speaking out against LGBTQ+ people. A compelling portrait of Ashman emerges—one in which the late artist weaved a desire for LGBTQ+ visibility into his work on beloved Disney movies.

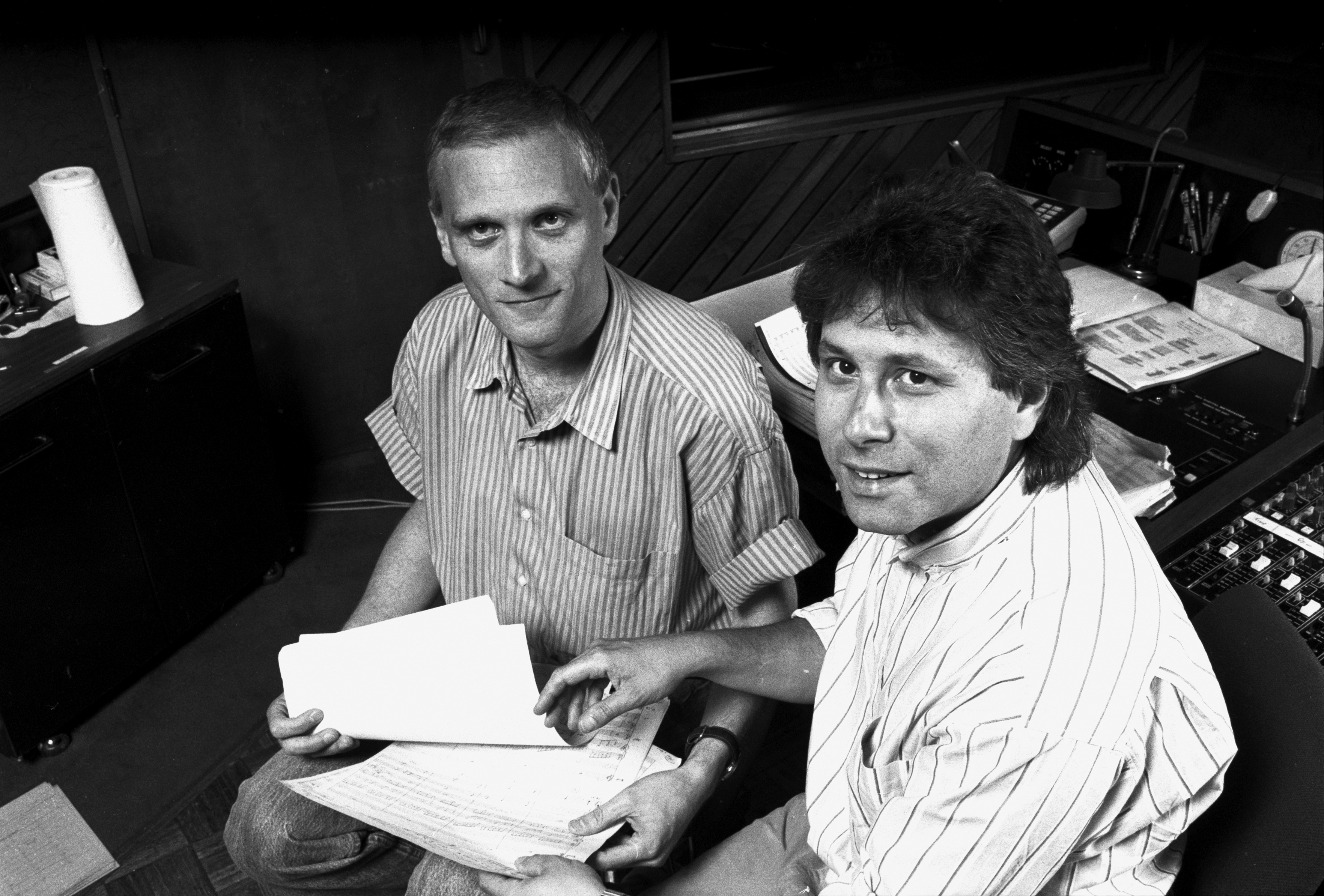

Howard, which made its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival earlier this year, is a spellbinding ode to Ashman, who died in 1991 due to AIDS-related complications. The film spans his relatively short career, from directing musicals in his Baltimore backyard to creating some of the most memorable lyrics in film and theater. It features the voices of his family members, his partner Bill Lauch, Jodi Benson (the voice of Ariel in The Little Mermaid), and his longtime collaborative partner, composer Alan Menken. The film serves as the perfect platform for audiences, new and old, to experience his work. We’ve heard his songs a million times before, but what’s unique is how the film points to the queer experience Ashman subtly expressed through his music.

His 1982 Off-Off-Broadway smash, Little Shop of Horrors, is one of the best examples of Ashman pushing the narrative beyond the storyline. In the adaptation of Roger Corman’s 1960 B-movie about a cannibalistic plant, Ashman spun it into a parody of the American musical and a satire of the American Dream. At its core, Little Shop is a story about wanting to live your truth. In Ashman’s version, it becomes a parable for the destructive natures of repression and the desire for the kind of heterosexual domesticity emblematic of Reagan-era politics (not to mention the way blood itself feeds what later becomes an epidemic).

In 1986, Ashman joined Menken to pen the lyrics for songs in Disney’s The Little Mermaid, a fairy tale based on Hans Christian Andersen’s forbidden love letters to another young man. Ashman penned “Part of Your World” and ”Under the Sea” while the comparisons between the villain, Ursula, and the drag legend, Divine, are more than superficial. This was Ashman’s vision at his most flamboyant and fabulous, and his most assured. When “Part of Your World” was almost cut by Walt Disney Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg for testing poorly in early test screenings, Ashman fought for the song likening it to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” in The Wizard of Oz, another queer anthem that pleads for a place where “the dreams that you dream of […] really do come true.”

Though the queerness of his songs was primarily subtextual, Ashman made a statement with his early 80s song, “Sheridan Square.” The song was created in remembrance of the people who were dying of AIDS, inspired by the diagnosis of Ashman’s ex-boyfriend, Stuart White. Referring to a tiny park in New York’s West Village, a booming haven for LGBTQ+ people, Ashman asked, “And why is it still so quiet tonight on Sheridan Square?” He was witnessing the crisis firsthand, and this touching song was both a memorial and a cry for help.

Then, it reached him. In 1988, as The Little Mermaid was wrapping, production on Aladdin was picking up, and Beauty and the Beast was in full swing, Ashman was diagnosed with HIV. He kept his illness a secret from most people. When hospitalization became a necessity, it did not keep him from working. He wasn’t present for several of the recording sessions for Beauty and the Beast, but would take phone calls and work from his bed, an indication of how much the production still needed him.

Although he was seemingly hesitant to insert much of his personal life in his work, Ashman’s identity nevertheless came through. Several of the people interviewed for the film make a concerted effort to suggest Ashman’s work was not political—that his sense for human empathy and spirit was what made his work memorable—but it’s the personal aspects of his work that made it inherently pointed. Though he died on March 14, 1991, he would win a posthumous Academy Award for Original Song for “Beauty and the Beast,” the first Oscar to be awarded to someone who had died from AIDS complications.

Ashman’s legacy, as the documentary attests, is predicated on his desire to acknowledge the LGBTQ+ experience in his work. He joked that he never believed Disney would allow a five-minute opening number for Beauty and the Beast, which described Belle and her “provincial life” with detail, patience, and beauty. “I’m afraid she’s rather odd / Very different from the rest of us,” the townspeople sing in “Belle.” Before the dandyish candelabra and the angry mob—before Disney released Pride merch and Frozen‘s Elsa came out of the closet—Ashman understood and expressed the desire to be seen.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Kyle Turner on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.