This Is the Secret to Unforgettable Photos

For art lovers, visiting Fotografiska, the photography museum in Stockholm, is a must. It’s home to one of the largest photography collections in the world and has mounted exhibitions of work by many of the best photographers throughout history.

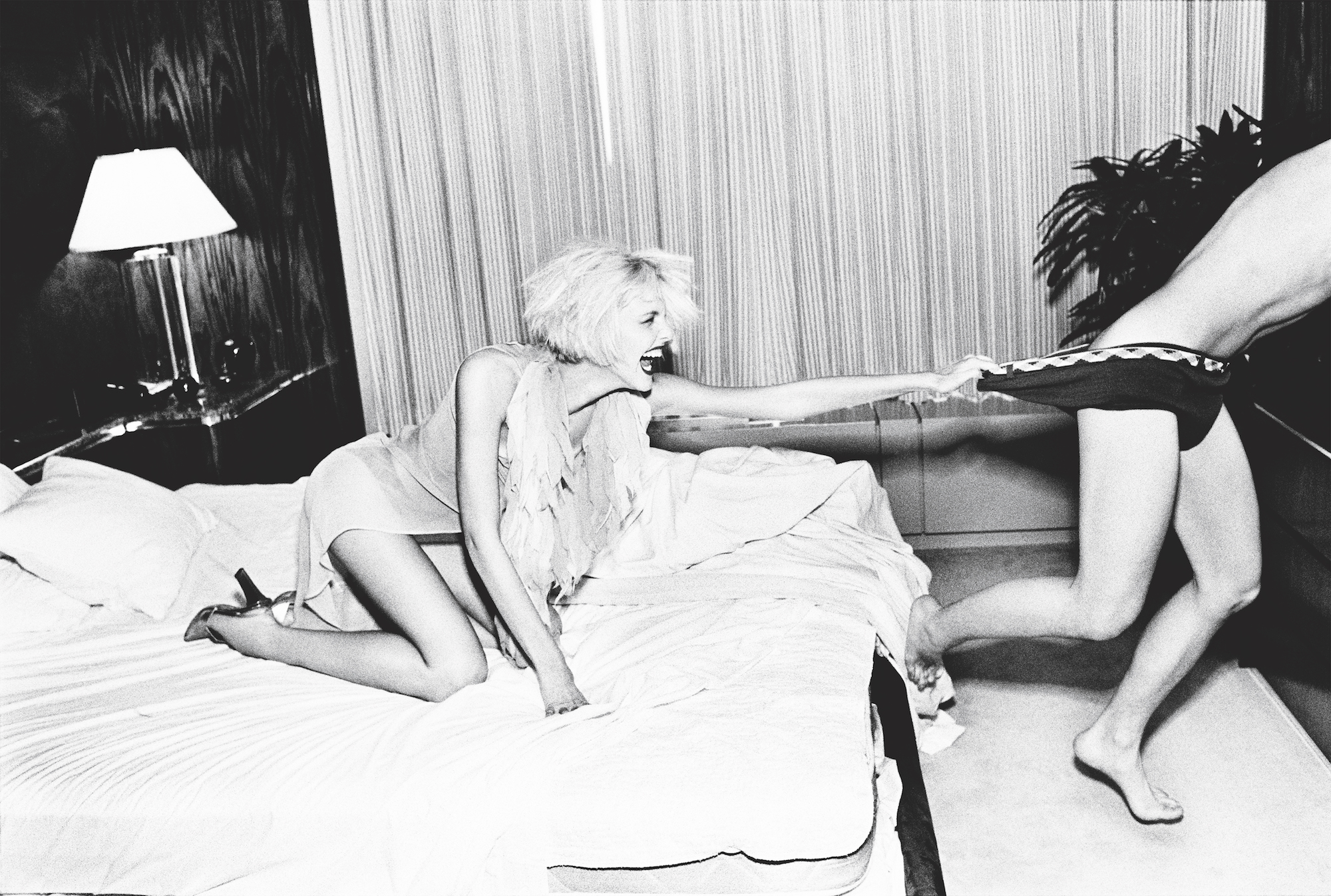

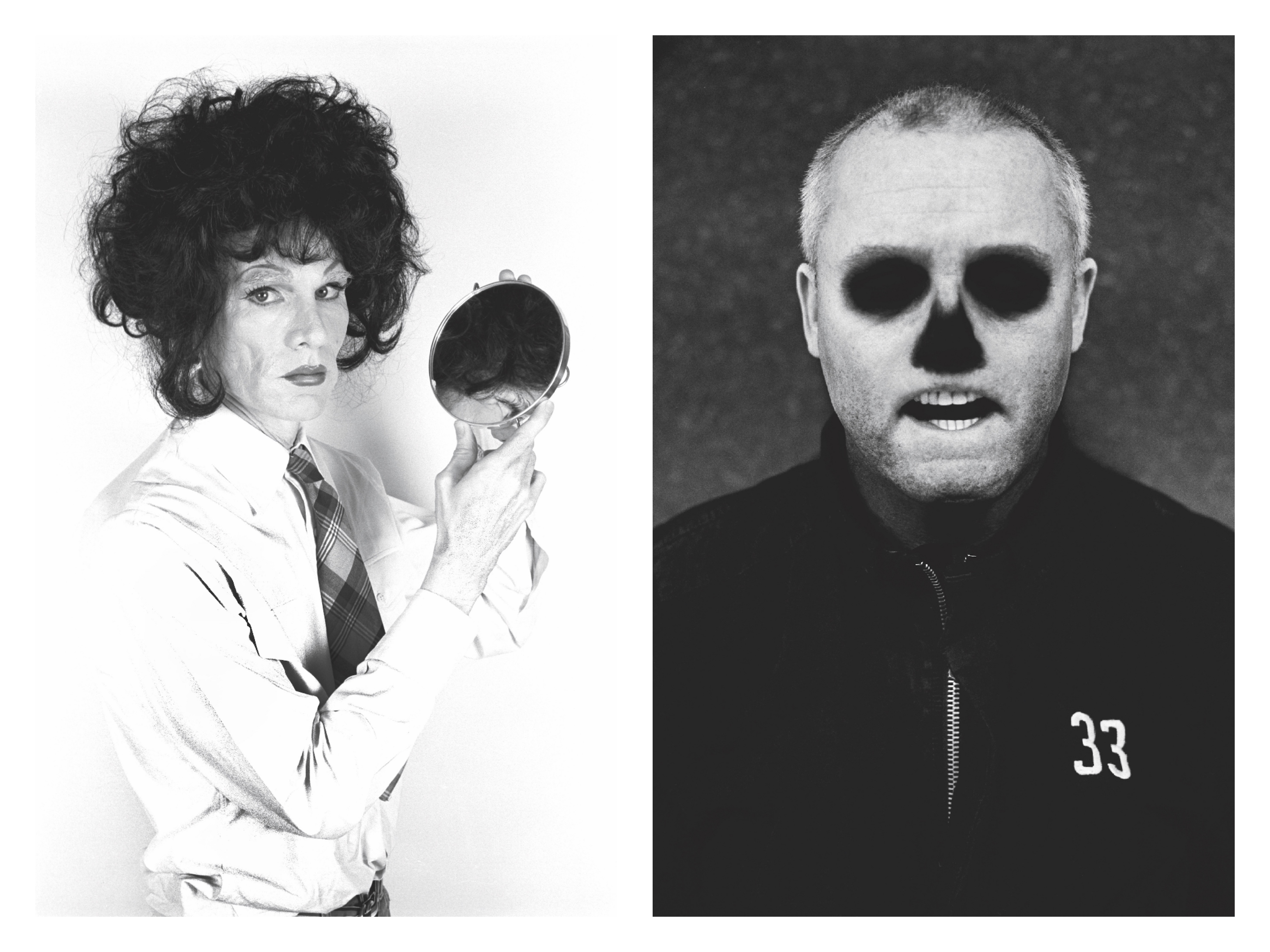

Fotografiska is in the process of expanding its international presence, opening new locations in London and New York in early 2019. To commemorate the new outposts, the museum just released The Eye by Fotografiska (teNeues), a monumental photography book featuring work by artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, Ren Hang, Gus Van Sant, and Annie Leibovitz, among many more. Featuring more than 250 photos by about 80 photographers, the book is a love letter to the camera and the way it transforms how we perceive the world.

Scottish photographer Albert Watson appreciates the power of photography more than most. Over five decades, he has established himself as a master of the medium, working across all genres. Whether photographing Michael Jackson for the cover of Invincible or Tupac for Juice, Watson has been creating iconic images since 1973, when he shot his first professional portrait of Alfred Hitchcock wringing the neck of a rubber chicken.

Watson wrote a rare essay, published in The Eye, reflecting on the elements that make a photograph unforgettable. VICE caught up with him recently to talk about the power of the medium, at a time when nearly everyone with a smartphone holds the power to create images and distribute them instantaneously.

VICE: Could you describe the fundamental power of photography?

Albert Watson: No one can stop time. It’s almost like the present doesn’t exist. The remarkable thing about photography was always the idea of being frozen in time.

How has digital photography changed the medium?

In the past, something like 2-3% of people were amateur photographers; they would take a camera with them when they went on holiday to take snapshots, and maybe birthdays and Christmas. Now it’s something like 60% of people regularly taking pictures on their smartphones. This changes how you see and appreciate photography because you are taking pictures all the time, not just on special occasions.

Smartphones made everybody able to take a decent picture because it does all of the technical things for you. They have lifted a lot of the mystery of photography and made it more available for the masses and I like it. People are more aware of photography and appreciative of what professionals can do. It’s very hard to elevate photography but there are always people who are passionate about, driven by, and are obsessed with photography—and through time, they get better and better.

Could you speak about the qualities that make a photograph iconic?

Memorability—you are always searching for that. You need a discipline for observation. Some people just go out first thing in the morning and they walk around the world, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, and they find things—they are just looking, finding. It is important that you remain switched on. You are always looking for images that are remarkable.

While I was working on the Las Vegas project around the time of 9/11, I passed a neon billboard, about 40–50 feet across. It was the middle of the day so you could barely see the words “God” “Bless” “America” pop up on the screen, one after another, and then behind that, the American flag. I looked at it and thought, “There’s not a picture there right now, but I bet if I come back when the sun begins to go down, the billboard will become illuminated so you can really see it.”

I stopped to get a good look and mapped out where the 8×10 camera could go. Then we came back at 6 PM and I was able to get the shot. We did it as a triptych, with three pictures of the screen. It was fairly straightforward, but it was conceptualization. One of the weaknesses in photography is not enough thought goes into it. A problem facing a lot of photographers is how do you make that shot powerful and unforgettable? If you get a decent image in your mind, you can go out and execute it—like Monkey with a Gun.

How did the idea of the photo Monkey with a Gun come about?

I had done an advertising job with that very chimpanzee. The monkey really enjoyed the whole experience. He was continually getting attention and loved being there. In fact, we had a problem at the end of the shooting because the monkey didn’t want to leave.

During the shoot, I noticed that if I put my hand on my head the monkey would put his hand on his head the same way. I immediately thought, “This is just great.” We brought in a lot of different clothes and props to work with the monkey and have fun with it. It was a perfect way to get a lot of very interesting images. The idea of handing a gun to a monkey was unusual. I knew it would be a provocative image. It’s a conceptual piece. I shot it graphically, but it was a simple shot.

Looking at the work in The Eye, can you share any insights into what has elevated the photographers in this book to the top of their game?

As you go through the book there is a lot of work that is memorable. The photography here is conceptual, challenging, and quite strange in some cases, and I think it makes the book interesting because of that. Sometimes they are graphically memorable, sometimes they have a strange kind of minimalism, but a lot of them have a quality that makes them compulsive, where you absolutely stare at them. They are like little tattoos that stay in your brain.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Miss Rosen on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.