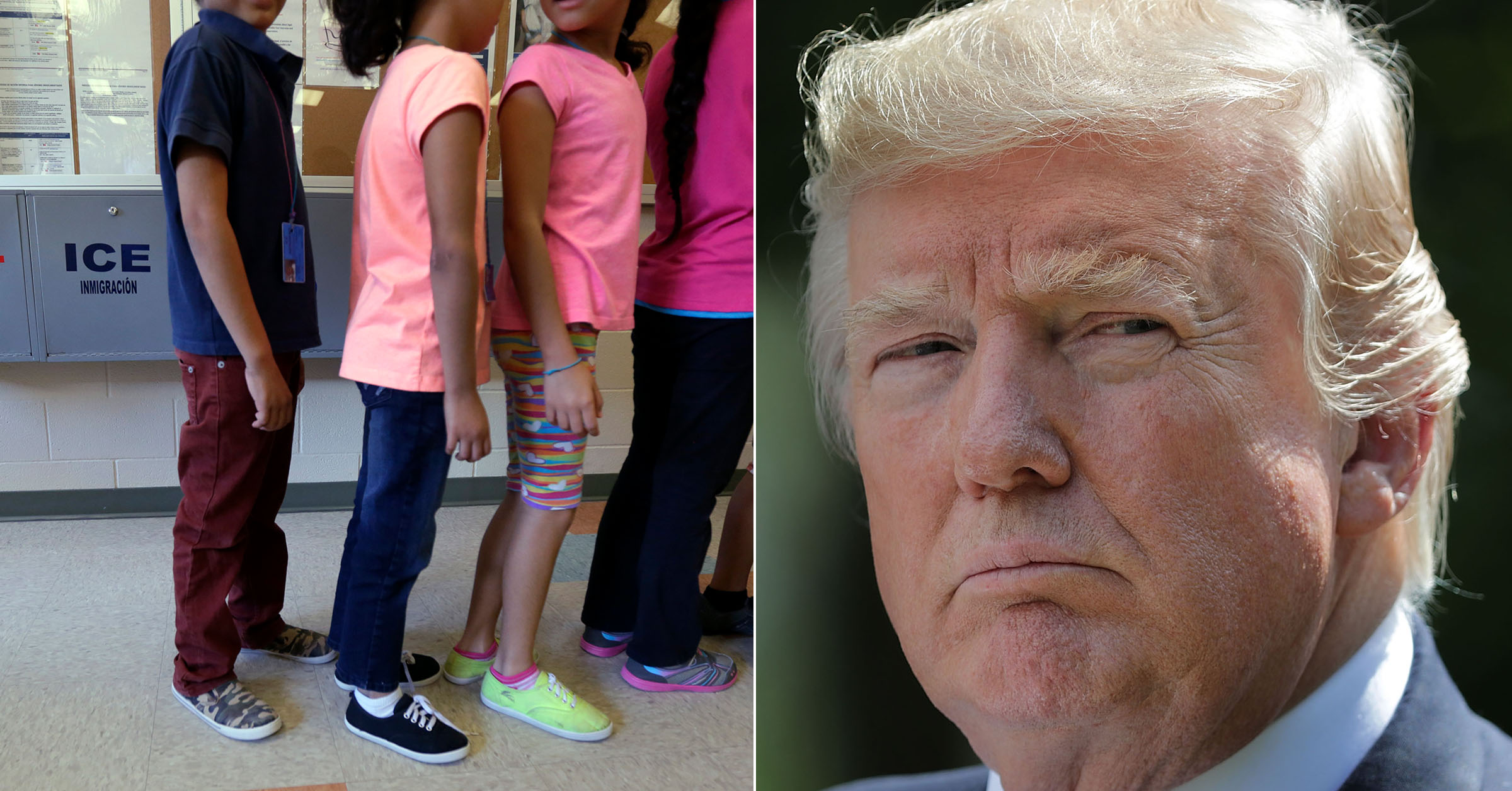

Trump Has Quietly Cut Legal Aid for Migrant Kids Separated from Parents

When the Trump administration announced this month it would criminally prosecute everyone who crossed the border illegally, which meant jailing immigrant parents and separating them from their children, it effectively manufactured a whole new group of unaccompanied minors who now must navigate the complicated US immigration system by themselves. In less than two weeks, 658 kids were divided from their mothers and fathers—and the policy is still ramping up.

Meanwhile, the government has just quietly shut off a legal lifeline for this very population, putting them at an even higher risk of deportation. The Office of Refugee Resettlement, a federal program that for over a decade has funded organizations representing unaccompanied minors in immigration court while those children live with adult relatives or guardians, told the groups to stop taking new cases just days after the family separation policy began, multiple sources from nonprofit groups funded by ORR told me.

“The government is creating unaccompanied kids, then releasing them to someone other than parents, and then further restricting their ability to access counsel,” said Manoj Govindaiah, director of family detention services for Texas’s Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES), which has represented kids through the ORR funds. “So they’re almost ensuring people cannot successfully navigate the immigration court process.”

RAICES, which typically represents about 300 unaccompanied minors a year in the Dallas-Fort Worth area thanks to ORR funding, had just screened a new round of applicants when they received the announcement earlier this month to accept no further cases, staff attorney Jennifer de Haro told me.

“We had to call all the families back and tell them we couldn’t provide them free services anymore,” she said.

At least 1,000 children each year—a small yet significant portion of the tens of thousands of unaccompanied minors—have received representation through ORR funding, which is administered through the nonprofit Vera Institute to about a dozen organizations nationwide, immigration sources told me. ORR gave no reason for its sudden end to this program, nor did its spokesperson return multiple requests for comment.

Slashing legal services while throwing more youths into the immigration system will inevitably lead to these vulnerable kids being deported, advocates told me. Immigrants have no right to counsel in these proceedings, and children formerly tied to their parents’ cases will now generally have their own cases. That’s because proceedings must go forward where each individual is located, and a parent could be detained in a different state from the shelter or sponsor of their child. Additionally, any parent in detention is put on a detained docket, which cannot include non-detained family members.

This means far more kids will be representing themselves in immigration court—and according to recent data compiled by the online tool TRAC, unrepresented children are far more likely to lose their cases than those who have lawyers. Not only is it nearly impossible for the kids to fully understand how to present their cases, but many of the children simply are too nervous to appear in court without a lawyer—and if they miss just one hearing, a judge can order them deported, de Haro explained.

“A lot of children are going to be too afraid to go to court and are not going to understand their legal rights,” she said.

Past ORR grants have helped de Haro reverse deportations for severely traumatized children who avoided court thinking they’d show up and immediately be sent back to their home countries. Two sisters from Guatemala, who were 12 and 15 years old when they arrived in the US in 2015, had been kidnapped, then watched by armed guards and subject to forced labor until the girls’ parents sold all their belongings to pay their ransom. The family had nothing left for legal fees so the girls skipped their first hearing, but then received a deportation order. With ORR funds, De Haro was able to reopen the girls’ case, which remains pending.

“They felt more at ease going to court, knowing that their removal order wouldn’t happen at the first appearance,” said de Haro, who also recently won permanent residency for two brothers who’d been initially ordered deported.

“The saddest part is, this all came when there was all this media attention on the lost children.”

–Camila Alvarez

But now RAICES and other organizations providing free legal services for children are scrambling to find other sources of funding—and as they represent fewer youths, some advocates worry even more children could get lost in the system.

Unaccompanied minors have already been going missing at a stunning rate: Last month the Department of Health and Human Services disclosed that ORR had lost track of roughly 1,500 unaccompanied minors after they had been placed with adult sponsors. But if these children had attorneys, they likely would not have been lost, advocates told me.

“The saddest part is, this all came when there was all this media attention on the lost children,” said Camila Alvarez, managing attorney of the immigrant advocacy organization CARECEN’s unaccompanied minor legal representation project. “And representation of the children definitely helps in reducing the children who are missing because they don’t have attorneys and are afraid to go to court.”

In Los Angeles, CARECEN has used ORR funds to represent at least 100 unaccompanied kids annually, and Alvarez said her organization is now scrambling to find other funding sources to continue their work.

“It’s definitely impacting our entire program,” she said. “We’ve been having a lot of conversations about shifting things, about how we are going to proceed with the representation.”

Children helped by organizations like CARECEN and RAICES are the lucky ones: The vast majority of unaccompanied minors do not have legal representation, and that proportion will almost certainly increase thanks to the uptick in family separations. Dana Marks, the president of the National Immigration Judges Union, said the surge of kids’ cases without lawyers will throw a wrench in the backlogged court system by “adding a whole level of complexity unnecessarily to cases.”

On top of that, Attorney General Jeff Sessions has just made it more difficult to adjudicate kids’ cases by ordering immigration judges to end a common practice, Marks told me. In the past, judges have frequently issued administrative closures (temporary holds) on unaccompanied minors’ cases while trying to determine the legal status of the children’s family members. That could have been used even more with children separated from their parents, as judges await decisions on the parents’ cases—but Sessions this month put an end to the it, pushing judges to potentially issue rulings prematurely.

“We’ve lost a valuable tool in dealing with children’s cases,” Marks told me.

Department of Justice spokesman Devin O’Malley responded that Sessions ended administrative closures as a way to stop suspending cases indefinitely, thereby shielding undocumented immigrants from deportation.

“Starting in 2012, immigration judges began increasingly to rely on administrative closures, which suspended cases indefinitely rather than actually rendering a final decision,” he said in an emailed statement. “This process—where immigration court cases were put ‘out of sight, out of mind’—effectively resulted in illegal aliens remaining indefinitely in the United States without any formal legal status.”

Meanwhile, Marks said the administration’s recent changes to immigration policy and the courts could have effects beyond what is even currently comprehensible.

“We all feel like it’s a seismic shift,” she said, “but it will take months if not years before we understand the true impact of what’s occurred.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Meredith Hoffman on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.